Running head: RURAL ACCENT STEREOTYPE

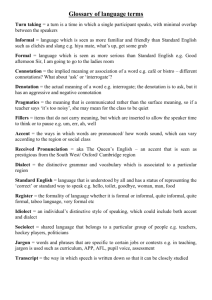

advertisement

Midwestern Rural Accent 1 Running head: RURAL ACCENT STEREOTYPE Midwestern Rural Accent Stereotypes Doug Hardesty and Claire Morgan Earlham College Midwestern Rural Accent 2 Abstract How individuals with rural accents are perceived was investigated. Researchers hypothesized that accented speakers would be seen as less effective and less educated than a control. Thirty-two participants listened to an audiotape with either a standard urban or a Midwestern rural accent. The speaker was identified as being either from Earlham College or Richmond, Indiana. Participants completed a survey describing how effective they believed the speaker was. A statistically significant interaction, F(1,32) = 5.36, p .05, for the speaker’s motivation and a main effect for residence, F(1,32) = 4.83, p .05, describing how well-educated the speaker appeared were found. The hypothesis was thus only partially supported. Midwestern Rural Accent 3 Midwestern Rural Accent Stereotypes A stereotype may be defined as a set of rigid beliefs, positive or negative, about the attributes of a group (Punzo, classroom lecture, 2003). These beliefs influence how groups and group members are perceived and evaluated. Oftentimes, certain characteristics are attributed to a given group. These characteristics are closely linked with how the group is expected to act or perform. The strength of this influence can be seen in an experiment performed by Darley and Gross (1983). In this study, participants were led to believe that “Hannah” came from either a low socioeconomic (SES) background or a high socioeconomic background. The participants were then asked to evaluate the child’s performance on completing several math problems. While the child’s performance in both cases was the same, participants who believed that the child came from a high-SES background rated the child’s performance above grade level. Participants who believed the girl came from a low-SES background rated the child’s performance below grade level. These results indicate that stereotyping-cuing information, such as the girl’s socioeconomic background, led participants to make assumptions about Hannah’s intellectual abilities. These assumptions can lead to prejudice, when group members are expected to act in negative ways (Allport, 1954). Accented speech can affect a listener’s impressions about a speaker (Giles & Powesland, 1975). In particular, non-standard accents are often thought of less favorably than standard accents. This thought process leads to prejudice against individuals with non-standard accents. Midwestern Rural Accent 4 Certain regional accents lend positive or negative traits to speakers. In one study, researchers investigated how various Irish regional accents affected students’ impressions of a man reading a passage on Irish history (Edwards, 1977). The matched-guise technique was used to record five stimuli accents. Students then rated each speaker on nine qualities, such as intelligence, ambition, and friendliness. Regional accent had a significant effect on all traits, with a Donegal accent rated most positively, and a Dublin accent rated least positively (Edwards, 1977). The negative effects of accent prejudice have been powerfully demonstrated (Dixon, Mahoney, & Cocks, 2002). A study presented participants with an audiotape of a criminal investigation, in which a man was interrogated by the police. The researchers varied the accent of the accused man between standard British and Birmingham British using the matched-guise technique. The type of crime (blue- or white-collar) was also manipulated. Participants saw the non-standard Birmingham accent as more guilty, especially when the crime was described as blue-collar (Dixon, Mahoney, & Cocks, 2002). Some of the prejudices that arise from non-standard accents are associated with class. Speech and accents are used as social cues (Foon, 1986). Thus, some of the prejudices against accented individuals may be reflective of the prejudices against the social class that such an accent presents. Participants in the British accent study (Dixon, Mahoney, & Cocks, 2002) may have linked the stereotypically lower-class Birmingham accent with the stereotype that blue-collar crimes are committed by poor individuals. Lastly, the median household income in Wayne County (in which this study takes place) is $34,885 per year, whereas the average income of a student’s family is $69,400 Midwestern Rural Accent 5 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000; Arnold, personal correspondence, 2003). Students may consider community members to be of a lower class and stereotype them accordingly (Foon, 1986). A rural accent, which many community members have, may also cue these class stereotypes due to association. In summary, a non-standard or regional accent can negatively affect the way a speaker is viewed. Some of these prejudices are activated due to the social class stereotype an accent holds. These prejudices have negative consequences for individuals with non-standard accents. There is a class discrepancy between local community members and students at the college, which may cue stereotypical class beliefs, regardless of accent. This leads researchers to hypothesize that individuals with Midwestern rural accents, such as local community members have, will be stereotyped by students. This stereotype will be stronger towards individuals with rural accents that are also identified as being from the local community, due to the class discrepancy between students and local citizens. This stereotype will manifest itself in lower ratings of the intelligence, education, and competence of a speaker with such an accent, when compared to a control. Method Participants Thirty-two students at Earlham College were used as participants. A portion of the participants were known by the researchers, but most were recruited via announcements in psychology courses. Extra credit points were offered to those participants recruited from courses. Participants were not filtered by age, sex, race, class year, place of origin, or socioeconomic status. Midwestern Rural Accent 6 Materials Participants listened to an audio recording of a man reading a 30-second passage on minimum wage increase. The matched-guise technique was used to record the audiotape in either a standard urban American accent (control condition), or a Midwestern rural accent (experimental condition). The voice actor read the following passage: Americans need an increase in wage! Minimum wage in this country has gone up only 200% since 1970. Living expenses have gone up 500%. This isn’t fair! Even working more than 40 hours a week, people on minimum wage can’t longer afford basic needs of life. More and more paychecks are going towards taxes and welfare instead of supporting hard-working families. Why can’t the government raise minimum wage to a reasonable level? I don’t see how factory workers can continue to live like this. If someone doesn’t do something soon, there are going to be a lot of good people living on the streets! Participants completed a questionnaire after hearing the tape. Three Likert-scale questions asked participants to evaluate the speaker’s effectiveness, persuasiveness, and his knowledge of the issues involving minimum wage increase. Two Likert-scale questions asked participants to rate the education level of the speaker, and if the speaker’s motivation for speaking was for his own financial benefit. All Likert-scale items were on a seven-point scale, with 1 being strongly disagree, and 7 being strongly agree. Participants were also asked to select two words they believed best described the speaker: wealthy, trustworthy, idealistic, middle-class, underpaid, condescending, ignorant, unhappy, passionate, upset, confident, or hopeful. The background information of Midwestern Rural Accent 7 participants was also gathered, including gender, class year, parent’s annual income, highest level of education obtained by either parent, state/country of origin, and if the participant worked or volunteered in the local community. Procedure Participants were told that the experimenters were conducting a study on public speaking. Participants were randomly assigned to listen to a speaker with either a Midwestern rural accent or a standard urban accent. Upon dividing participants into groups, they were taken into different rooms and given a handout describing the speaker. The speaker was identified on the handout as being either from the local community of Richmond, Indiana or from Earlham College, depending on the condition to which the participant had been assigned. Therefore, there were four conditions: a rural accent from Richmond, a rural accent from Earlham, a standard accent from Richmond and a standard accent from Earlham. Participants were told the recording came from a local community meeting in 2001. Participants then listened to the stimulus material (the audiotape) and completed a survey. The survey asked questions pertaining to the speaker’s performance and the personal background of the participant. After completing the survey, participants were debriefed and told the true nature of the study. Results A 2 (Accent Type) X 2 (Residence) factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for each of the speaker evaluation items. Analysis of the financial motivation of the speaker yielded a statistically significant interaction, F(1,32) = 5.36, p .05. These findings indicate that participants in the standard accent, college condition did not believe Midwestern Rural Accent 8 that the speaker was arguing for his own financial gain as compared to participants in the other three conditions. No main effects were found for accent type or residence when examining the speaker’s financial motivation for speaking. Analysis of how well-educated the speaker was perceived as being revealed a main effect for residence, F(1,32) = 4.83, p .05. In both the rural accent and standard accent conditions, speakers described as being from the college were seen as better educated than those described as being from the community (refer to Table 1). No interaction between accent type and residence for this variable were found. Intelligence, influence or knowledge of the speaker did not yield any significant interactions or main effects. No significant results were found for the adjective selection in which participants described the speaker. Discussion In this study, participants listened to a brief audio recording of a man speaking about minimum wage increase. Accent (Midwestern rural or standard urban) and residence (Earlham College, or Richmond, Indiana) were independent variables. Researchers hypothesized that both a Midwestern rural accent and being identified as from the local community would negatively affect participants’ impressions of the speaker. Researchers also predicted that accent and residence would affect how educated the speaker appeared, and if the speaker was arguing for his own financial gain (i.e., if he was employed in a minimum-wage job). The hypothesis was only partially supported. Two statistically significant results were found: an interaction between accent and residence on the speaker’s motivation, and a main effect of residence of speaker on perceived education level. Midwestern Rural Accent 9 The interaction between accent type and residence in relation to the speaker’s financial motivation for speaking partially supported the hypothesis. As expected, the standard accent, college speaker was described as being the least likely to be speaking for his or her own financial gain. Surprisingly, the rural accent, college speaker was described as being the most likely to be speaking for an increase in personal financial gain. Researchers anticipated that the rural accent, community member would be perceived as the most likely to be speaking for such a reason. It is possible that the rural accent, college speaker was considered more capable of strongly arguing for such a point. This suggests that education level may be more of a deciding factor than accent type in evaluating the effectiveness of a speaker. It is possible that the stereotype held by college students towards community members was not as strong as had been anticipated. Participants considered the speaker less educated when identified as being from the local community. The standard accent speaker identified as being from the college was rated as being the most educated; the rural accent speaker identified as being from the college was rated second most educated out of the four conditions. Participants may have assumed the speaker was an Earlham student or faculty member, even though he was identified as “a man from Earlham College.” These results indicate that Earlham students seem to view citizens of the local town as less educated than members of the Earlham community. Several problems may have influenced the results of this study. One was the limited sample size, with only eight participants in each condition. Significant results may have manifested in other categories had there been a greater number of participants. Midwestern Rural Accent 10 Another area of concern was the stimulus material. The voice actor, although convincing, was not a replacement for a native rural accent. Some of the finer distinctions in the Midwestern rural accent may not have been accurately represented. The prejudices of participants may have been cued more strongly had a native speaker been used in the audio recording. Because the tapes were identical except for accent type, no mannerisms or slang words were used. This may have lessened the intended stereotyping-cuing effect of the tape. Lastly, two-thirds of participants were freshmen. It can be assumed that freshmen have had less contact with the local community than have upperclassmen. Increased contact might result in more, or less, prejudice against community members. In future studies it would be interesting to see if perceived education level is a more influential factor than accent type in evaluating the effectiveness of an individual’s public speaking ability. It would also be useful in the context of accent study to examine whether the word choice and mannerisms of a speaker or a speaker’s accent influences participants’ perceptions more strongly. Midwestern Rural Accent 11 References Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley. Darley, J.M., & Gross, P.H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20-33. Dixon, J., Mahoney, B., & Cocks, R. (2002). Accents of guilt? Effects of regional accent, race, and crime type on attributions of guilt. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 21, 162-168. Edwards, J.R. (1977). Students’ reactions to Irish regional accents. Language & Speech, 20, 280-286. Foon, A.E. (1986). A social structural approach to speech evaluation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 126, 521-530. Giles, H., & Powesland, P.F. (1975). Speech evaluation and social evaluation. London: Academic Press. U.S. Census Bureau (2000). 2000 census of population and housing. Retrieved December 4th, 2003, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/18/18177.html Midwestern Rural Accent 12 Table 1. Means and standard deviations for apparent education of speaker and motivation of speaker. Midwestern Rural Accent Community College Perceived level of education Standard Accent Community College 3.625 4.375 4.000 4.875 Standard dev. 1.06 0.916 1.20 0.991 Motivation of speaker* 3.000 3.625 3.375 2.000 Standard dev. 0.926 1.60 1.19 1.07 * Higher means reflects agreement that the speaker was arguing for his own financial benefit