Bolsa Escola in Brazil

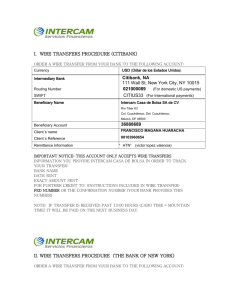

advertisement