11. The Bureaucracy - Mr. Tyler's Lessons

advertisement

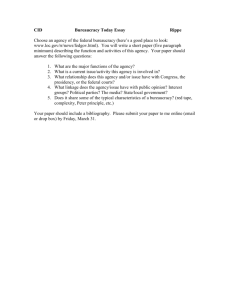

Bureaucracy Assignment Part I: Instructions: Use Short Answer Essays, Graphic Organizers/Diagrams, or Bullet Outlines to demonstrate your understanding of the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. The Nature of Bureaucracy The Size of the Bureaucracy The Organization of the Federal Bureaucracy Staffing the Bureaucracy Modern Attempts at Bureaucratic Reform Bureaucrats as Politicians and Policymakers Congressional Control of the Bureaucracy Part II: Investigating: The Bureaucracy --Give a brief description of the each cabinet department (15) Part III: The Bureaucracy --Give a brief description of 10 independent executive agencies LEARNING OBJECTIVES After students have read and studied this chapter, they should be able to: Explain the differences between private and public bureaucracies. Identify the models of bureaucracy. Explain how the bureaucracy has developed throughout our history. Identify the types of governmental organizations in the federal bureaucracy and distinguish between functions and responsibilities (including Cabinet departments, independent executive agencies, independent regulatory commissions and government corporations). Identify the legislation controlling political activity by the bureaucracy (the Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 and the Hatch Act). Explain Congressional control on bureaucracies, including enabling legislations and budgetary authorization. Identify the recent reforms within the federal civil service. o Sunshine laws o Sunset laws o Whistle-blowers Explain the iron triangle model of the bureaucracy and the role of executive agencies, subcommittees and interest groups. TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION How necessary is bureaucracy? If we can agree that individuals need rules and regulations to live together, then there must also be a bureaucracy. Rules and regulations are meaningless unless they are administered; the bureaucracy is necessary for the administration. An example of a bureaucracy that students should be able to identify with is the one at your college or university. Each professor is a specialist who is a part of a division or department (chain of command). Most professors use a syllabus (formal rules) and administer grades on an objective basis (decision-making based on neutrality). (Of course, we are more used to thinking of the university bureaucracy as including only non-teaching staff.) What could be done to eliminate iron triangles? Prohibit agencies from testifying before Congress? Where does Congress receive important information on how a program is functioning? (the agencies) Eliminate subcommittees in Congress? Why does Congress have subcommittees? (specialization.) Eliminate interest groups? How is that possible in a democracy? Ask the students to review Federalist #10. Although the term “iron triangle” had not yet been used, did Madison foresee problems of this nature? What action do you think Madison would advocate concerning the relationship between interest groups and the bureaucracy? In modern times, we tend to equate the term “bureaucracy” with “red tape” or “inefficiency.” How does the goal of neutrality and the need for specialization help reinforce those images? BEYOND THE BOOK Today, all Americans benefit from government services and regulations daily. Chances are that the government was involved in your life in many ways today. You may have driven to school in automobile that was subject of many federal safety and environmental regulations. You may have driven on federal highway, or a state road whose maintenance was supported with federal funds. Chances are that your school receives subsidies from the federal government, and some students attend with the help of federal grants or federally subsidized loans. Even the food you eat in the cafeteria is subject to federal regulation to protect your health, and if you receive mail today, it will have been delivered by a federal “bureaucrat” (that is, a letter carrier!). It is normally very hard to fire a civil servant, and few are dismissed even for the most conspicuous dereliction of duty of their jobs. One category of bureaucrat, however, is fired rapidly in almost all cases. When whistleblowers report agency fraud or abuse to the press or to investigatory bodies, managers somehow find it miraculously easy to fire them, despite the normal institutional barriers to dismissing civil servants and despite the existence of special legislation to protect whistleblowers. This suggests that the real reason that civil servants are rarely fired is not that it is truly impossible, but that managers have no motivation to go to the trouble of getting rid of employees who are merely incompetent. Only when an employee appears to threaten the agency itself (or the manager’s own job) is the manager stirred to action. Why managers normally have no motivation to fire anyone is a question worth pondering. 115 CHAPTER OUTLINE 1. The Nature of the Bureaucracy A bureaucracy is a large organization that is structured hierarchically to carry out specific functions. The purpose of a bureaucracy is the efficient administration of rules, regulations, and policies. Governments, businesses and other institutions such as colleges and universities perforce have bureaucracies. A. Public and Private Bureaucracies. Public bureaucracies are governmental bureaucracies that do not have a single set of leaders in the way that private or business bureaucracies do. The purpose of a private-sector company is to make a profit. A bureaucracy within a company will attempt to administer the policies of the company to maximize profits for the company. Unlike a private company, the government is supposed to provide services to the public. A governmental bureaucracy is concerned with administering policies that provide services to the people. These fundamental differences between public and private bureaucracies make comparisons difficult. B. Models of Bureaucracy. 1. Weberian Model. Analyses of how bureaucracies operate and how they should operate are often based on the work of Max Weber (pronounced VAY-ber), a famous German sociologist. Weber believed that all bureaucracies share certain qualities: Hierarchy. Every person who works in an organization has a superior to whom they report. Specialization. Workers have an area of expertise as opposed to being knowledgeable about all aspects of the organization. Rules and regulations. Decisions are made based on set rules and organizations treat all people the same based on these formal rules. Neutrality. Bureaucrats are supposed to administer the rules without bias. No one should be given preferential treatment. The Weberian model views bureaucracy as a hierarchically organized model with formal rules and regulations. Power flows from the top down. Decisions are technical in nature. The focus is placed on rational and unbiased decision-making. 2. Acquisitive Model. The acquisitive model is a view of bureaucracy where decisions are made for the needs of the top bureaucrats. Each division of the bureaucracy is most concerned with protecting the “turf” of the department and expanding the size of its budget. Once created, an agency will continue to seek new goals in order to justify the existence of the agency. 3. Monopolistic Model. This model views bureaucracy as the sole provider of a service. Without competition, the department has little or no incentive to be efficient, and typically is not penalized for waste or inefficiencies. C. Bureaucracies Compared. The sheer size of the U.S. bureaucracy—which follows from the sheer size of the country—may make the bureaucracy more autonomous than in some other 116 nations. Our federal system also limits the “top-down” system that empowers the political leadership. States may need to be persuaded rather than ordered. 2. The Size of the Bureaucracy In 1789, the size of the federal bureaucracy was extremely small. The federal bureaucracy has grown considerably since that time. Most of this growth has been the result of a continuing expansion of the role of the government. In 1789 there were few policies implemented by the federal government. State governments made most policies that affected the people. Today there are about 2.7 million civilian employees of the federal government. The two biggest employers are the U.S. Postal Service, with almost 800,000 workers, and the Department of Defense, with more than 650,000 civilian staff. In recent years, the greatest growth in government employment has been at the local level. Federal employment has remained stable. However, the federal government also uses a large number of contractors and subcontractors who are not counted as employees. Federal spending today is equal to about 30% of the nation’s GDP. 3. The Organization of the Federal Bureaucracy a. Cabinet Departments. The cabinet departments are the fifteen major service organizations of the federal government. They are the departments of: 117 Agriculture Commerce Defense Education Energy Health & Human Services Homeland Security Housing & Urban Development Interior Justice Labor State Transportation Treasury Veterans Affairs b. Independent Executive Agencies. These are governmental entities that have a single function and are not part of a cabinet department. The director of the agency reports to the president. Examples of these agencies include the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the General Service Administration (GSA), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). c. Independent Regulatory Agencies. These are agencies outside the major executive departments charged with making and implementing rules and regulations to protect the public interest. Examples include the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). i. The Purpose and Nature of Regulatory Agencies. These agencies are supposed to be independent of the rest of the government to guarantee their impartiality. In theory, their rulings should be based on the law and on technical knowledge, not politics. ii. Agency Capture. It is argued, however, that many agencies have come to be dominated by the industries they were meant to regulate. This process is called agency capture. iii. Deregulation and Reregulation. Calls for a reduction in the general level of governmental regulation met with success during the administrations of presidents Carter and Reagan. A degree of reregulation occurred under the elder Bush (George H.W. Bush). Under Clinton, some economic regulations were lifted, but environmental ones were tightened. d. Government Corporations. These are agencies that charge the public for a specific service. Examples of government corporations include the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the United States Postal Service, and Amtrak. They differ from private corporations in that they do not have shareholders, but are owned by the government. 118 4. Staffing the Bureaucracy Bureaucrats can be placed into two categories: political appointees and civil servants. a. Political Appointees. The president appoints individuals in the first category. The most important factor in this selection process is political party. The overwhelming majority of presidential appointees are of the same party of the president. These “political plums” are bestowed to qualified individuals who typically helped the president get elected. Among the biggest “plums” are ambassadorships. These may be reserved for large contributors to the president’s campaign. One of the most dubious political appointments in recent years was George W. Bush’s appointment of Mike Brown as head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Brown’s lack of expertise was revealed in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. i. The Aristocracy of the Federal Government. The powers of political appointees appear formidable on paper, but may be less so in reality. Often, such appointees lack detailed knowledge of the institutions they are running. They may be in place only two or so years and have little time to learn. Top career bureaucrats can often frustrate the plans of their political boss. ii. The Difficulty in Firing Civil Servants. The problem is compounded by the fact that firing a civil servant is a difficult and very time-consuming process. b. History of the Federal Civil Service. Historically, individuals of the party of the president staffed the bureaucracy. The first political party, the Federalists, held the early positions for the first twelve years of the government. When Thomas Jefferson was elected, he replaced many bureaucrats with members of his own party. The Jeffersonian Republicans controlled the government for the next twenty-four years, and so the bureaucracy did not turn over. i. To the Victor Belong the Spoils. Andrew Jackson found that many existing bureaucrats were unwilling to implement many of his programs. Thus, Jackson made the decision to fire more officials than any president before him, on the principle “to the victor belong the spoils.” Thereafter, whenever a president was elected who was of a different party from the previous president, most federal employees were replaced. ii. The Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. Reform of the bureaucracy selection process began in 1883. The Pendleton Act established the Civil Service Commission and created a situation in which civil servants were to be selected on merit, not political affiliation. At first only 10 percent of federal employees were covered, but the program expanded over time to cover most administrators. iii. The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978. This created the Office of Personnel Management to oversee testing and hiring, and the Merit Systems Protection Board to hear employee grievances. iv. Federal Employees and Political Campaigns. In 1939, the Hatch Act prohibited civil servants from active involvement in political campaigns. It sought to ensure a 119 5. neutral bureaucracy, and sought to protect bureaucrats from being pressured by their superiors to make political contributions or engage in campaigning. While some have complained that the Hatch Act violates the constitutional rights of civil servants who wish to be politically active, the Supreme Court ruled in 1973 that the government’s interest in preserving a nonpartisan civil service was so great that the prohibition should remain. The Federal Employees Political Activities Act of 1993 removed some Hatch act restrictions, allowing bureaucrats to participate in campaigns voluntarily. Modern Attempts at Bureaucratic Reform There have been a number of attempts at opening up the process of administering policy and making the bureaucracy more efficient and responsive to citizen needs. a. Sunshine Laws before and after 9/11. Sunshine laws require agencies to conduct many sessions in public. i. Information Disclosure. The 1966 Freedom of Information Act opened up government files to citizen requests for information, in particular about themselves. ii. Curbs on Information Disclosure. After 9/11, however, the government established a campaign to limit disclosure of any information that could conceivably be used by terrorists. b. Sunset Laws. These require legislative review of existing programs to determine their effectiveness. If the legislature does not explicitly reauthorize a program, it expires. While many states have enacted this process, unfortunately Congress has not made it the law in the federal bureaucracy. c. Privatization. The privatization of services occurs when the government contracts with the private sector for certain services, in the belief that some services can be provided more efficiently by private firms. This practice occurs more frequently on the local level. d. Incentives for Efficiency and Productivity. i. The Government Performance and Results Act of 1997 seeks to improve governmental efficiency by requiring government agencies to describe their goals and create mechanisms for evaluating whether these goals have been met. ii. Bureaucracy Changed Little, Though. One argument is that bureaucratic inefficiencies are the direct result of the political decision-making process. If Congress wants a more efficient bureaucracy, it should examine its own demands on the system. iii. Saving Costs through E-Government. The Internet has also improved the efficiency of federal government. Now, citizens can find information on government Web sites, and can communicate directly with government offices through e-mail. e. Helping Out the Whistle Blowers. The Whistle-Blower’s Protection act of 1989 was an attempt to encourage federal bureaucrats to report waste and fraud within agencies by 120 protecting them. It established the Office of Special Counsel to investigate complaints about government waste or inefficiency. 6. Bureaucrats as Politicians and Policy-Makers Although Congress has the power to legislate, it must rely on the executive branch to administer the laws. When Congress enacts legislation that is very precise the bureaucracy simply administers the law. However, it is rare that laws are so precise that there is no room for questions concerning interpretation and application. Therefore, the bureaucracy usually must make policy decisions concerning interpretation and application of a statute. This administrative discretion is not accidental. Congress has long realized that it does not have the technical expertise to draft laws that cover all contingencies. a. The Rulemaking Environment. Proposed rules are published in the Federal Register and interested parties have an opportunity to comment on the proposal. i. Waiting Periods and Court Challenges. Sixty days must pass before the rule goes into effect. Interested parties can ask the agency for changes or ask Congress to overrule the agency. Directly affected parties can also sue before or after the sixty days on the grounds the rule exceeds the agency’s mandate or is unfair. The courts tend to presume in favor of the agency in such cases—those objecting must have a strong case if they expect to win. ii. Controversies. An example of controversial administrative decisions involves the steps to implement the Endangered Species Act, which can interfere with the property rights of landowners. b. Negotiated Rulemaking. In an attempt to reduce the number of court cases challenging administrative decisions, the executive branch has encouraged interested parties to participate in the drafting of administrative decisions concerning laws enacted by Congress. This is called negotiated rulemaking. While negotiated rulemaking has not eliminated court cases of this nature, it has reduced the number of challenges to administrative decisions in certain policy areas such as the environment. Congress endorsed this policy with the Negotiated Rulemaking Act of 1990. c. Bureaucrats Are Policymakers. The federal bureaucracy has become a major source for decision-making concerning public policy. Different theories have been advanced to describe the impact of outside groups on the process. i. Iron Triangles. Key concept: An iron triangle, or a three-way alliance among legislators, bureaucrats, and interest groups that seeks to make or preserve policies that benefit their respective interests. Advocates of this theory usually believe that special interests have too much influence. The bureaucrats, then, no longer act as impartial administrators. Instead, bureaucrats act as agents for the special interests and attempt to influence Congress to enact laws that favor the special interest. The committee structure in Congress may help perpetuate this system. The members of Congress who serve on committees and subcommittees are interested in gaining 121 7. 8. support for their constituents who would benefit by the enactment of legislation favoring a particular special interest. ii. Issue Networks. Others assert that iron triangles do not fully describe the complex web of relations between the executive and legislative branches and interest groups. Most scholars now see the policy process as being one where issue networks dominate. That is, legislators, interest groups, bureaucrats, scholars and experts, and members of the media who share a position on a given issue may attempt to exert influence on the executive branch, on Congress, on the courts or on the media to see their policy position enacted. Obviously, issue networks with opposing positions may come into political conflict with each other. Congressional Control of the Bureaucracy a. Ways Congress Does Control the Bureaucracy. The ultimate control is in the hands of Congress because Congress controls the purse strings. Congressional control of the bureaucracy includes the establishment of agencies and departments, the budget process, and oversight conducted through investigations, hearings, and review. b. Reasons Why Congress Cannot Easily Oversee the Bureaucracy. While Congress is able to identify certain bureaucratic failures, especially the catastrophic mistakes such as the CIA and 9/11 and FEMA and Hurricane Katrina, there are so many bureaucratic shortcomings that there are not enough hours in the day or months in the year to identify them all. Features a. What If . . . The Public Graded Federal Bureaucracies? The resulting publicity could put pressure on poorly performing agencies. The reaction to FEMA in the wake of Hurricane Katrina demonstrates the disgust the people sometimes feel for the bureaucracy. Still, it is hard to see how true leverage over the bureaucracy could be obtained without making it easier for bureaucrats to be fired. b. Politics and Diversity: A Public Railroad, No Matter What the Cost. The government corporation Amtrak, which provides passenger rail service, loses $1-2 billion a year. Cross-county routes are especially unprofitable. Attempts to eliminate unprofitable routes run up against the opposition of the members of Congress from the affected districts. c. Which Side Are You On? Unifying Our Antiterrorism Effort Was the Right Thing to Do. The new Department of Homeland Security, established in 2003, united various agencies dealing with the threat of terrorism, the control of the borders, and natural disasters, a move that was seen by many as essential to protecting our security. However, it did not include agencies such as the FBI and CIA, which are key to the anti-terrorism effort and thus far the Department of Homeland Security has hardly been the success imagined by its advocates. 122 d. Beyond Our Borders: Privatizing the U.S. Military Abroad. While the call for privatization is sounded in Washington today, the military discovered the necessity and advantages of privatization over a decade ago. With the downsizing in the armed forces it has been essential to contract out any number of services formerly performed by uniformed personnel. There are over ten thousand private contractors on the ground in Iraq. Burns: Lecture Notes: LECTURE OUTLINE I. The Nature of the Bureaucracy A. A bureaucracy is a large organization that is structured hierarchically to carry out specific functions. The ideal purpose of a bureaucracy is the efficient administration of rules, regulations, and policies. Governments, businesses and other institutions such as colleges and universities have bureaucracies. B. Public bureaucracies are governmental bureaucracies that do not have a single set of leaders in the way that private, or business bureaucracies do. The purpose of a private sector company is to make a profit. A bureaucracy within a company will attempt to administer the policies of the company to maximize profits for the company. Unlike a private company, the government is supposed to provide services to the public. A governmental bureaucracy is concerned with administering policies that provide services to the people. These fundamental differences between public and private bureaucracies make comparisons difficult. C. Analysis of how bureaucracies operate and how they should operate are often based on the studies conducted by Max Weber (pronounced VAY-ber), a famous sociologist. Weber’s studies indicate that all bureaucracies share certain qualities. 1. Hierarchy - Every person who works in an organization has a superior to whom they report. 2. Specialization - Workers have an area of expertise as opposed to being knowledgeable about aspects of the organization. 3. Rules and regulations - Decisions are made based on set rules and treat all people encountering the organization the same based on these formal rules. 4. Neutrality - Bureaucrats are supposed to administer the rules without bias, no one should be given preferential treatment. D. Models of Bureaucracy 1. The Weberian model views bureaucracy as a hierarchically organized model with formal rules and regulations. Power flows from the top down. Decisions are technical in nature. The focus is placed on rational unbiased decision-making. 2. The acquisitive model is a view of bureaucracy where decisions are made for the needs of the bureaucrats. Each division of the bureaucracy is most concerned with protecting the “turf” of the department and expanding the 123 size of their budget. Once created an agency will continue to seek new goals in order to justify the existence of the agency. 3. The monopolistic model views bureaucracy as the sole provider of a service. Without competition, the department has little or no incentive to be efficient, and they typically are not penalized for waste or inefficiencies. II. The Size of the Bureaucracy In 1789 the size of the federal bureaucracy was extremely small in comparison to the size of the current bureaucracy. As Figure 12-1 in the text demonstrates, the federal bureaucracy has grown considerably since that time. Most of this growth has been the result of a continuing expansion of the role of the government. In 1789 there were few policies implemented by the federal government. Most policies that affected the people were made by state governments. Today, the services the population receives from the government are far more numerous than in the time of the founders. Much of the growth in the federal government took place following the implementation of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, which led the United States out of the Great Depression. New Deal programs, like the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Works Progress Administration required bureaucracies to administer them. Today, all Americans benefit from government services and regulations daily. Chances are that the government was involved in your life in many ways today. You may have driven to school in automobile that was subject of many federal safety and environmental regulations. You may have driven on federal highway, or a state road whose maintenance was supported with federal funds. Chances are that your school receives subsidies from the federal government, and some students attend with the help of federal grants or federally-subsidized loans. Even the food you eat in the cafeteria is subject to federal regulation to protect your health, and if you receive mail today, it will have been delivered by a federal “bureaucrat” (also called a letter carrier!) III. The Organization of the Federal Bureaucracy A. The cabinet departments are the fourteen major service organizations of the federal government. The George W. Bush administration included the following cabinet members as of April 2003: DEPARTMENT SECRETARY Secretary of Agriculture Ann Veneman Secretary of Commerce Don Evans Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld Secretary of Education Rod Paige Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham Secretary of Health & Human Services Tommy Thompson Secretary of Housing & Urban Development Mel Martinez Secretary of Homeland Secretary Tom Ridge Secretary of Interior Attorney General Secretary of Labor Gale Norton John Ashcroft Elaine Chao 124 Secretary of State Secretary of Transportation Secretary of Treasury Secretary of Veterans Affairs Colin Powell Norman Mineta Paul O'Neill Anthony Principi B. Independent executive agencies are governmental entities that have a single function that is not part of a cabinet department. The director of the agency reports to the president. Examples of such agencies include: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) General Service Administration (GSA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). C. Independent regulatory agencies are agencies outside the major executive department charged with making and implementing rules and regulations to protect the public interest. Examples include the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). D. Government corporations are agencies that charge the public for a specific service. Examples of government corporations include: Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA); United States Postal Service; and AMTRAK. IV. Staffing the Bureaucracy A. Bureaucrats can be placed into two categories: political appointees and civil servants. The president nominates individuals in the first category, and if the Senate approves the individual, the president will appoint the person to the bureaucratic position. The most important factor in this selection process is political party. The overwhelming majority of presidential appointees are of the same party of the president. These “political plums” are bestowed to qualified individuals who typically helped the president get elected. The biggest “plums” are ambassadorships. These are typically reserved for high contributors to the president’s campaign. B. Historically, the bureaucracy was staffed by individuals of the party of the president. The first political party, the Federalists held the early positions for the first twelve years of the government. When Thomas Jefferson was elected he replaced many bureaucrats with members of his own party. Andrew Jackson was credited, or blamed for furthering this tradition in 1828 with the so-called spoils system. Jackson was faced with Jefferson’s “natural aristocracy” bureaucracy. Many of these bureaucrats were unwilling to implement many of his populist programs. So Jackson fired many officials, citing “to the victor belong the spoils.” C. Reform of the bureaucracy selection process began in 1883. The Pendleton Act established the Civil Service Commission. Civil servants, the second category of bureaucrats, are selected on merit not political affiliation. D. Further reform came in 1939 with the passage of the Hatch Act. This act prohibited civil servants from active involvement in political campaigns. It sought to ensure a neutral bureaucracy, and sought to protect bureaucrats from being pressured for political contributions by elected officials. While some have complained that the Hatch Act violates the constitutional rights of civil servants who wish to be politically active, the Supreme Court has ruled that the 125 government’s interest in preserving a nonpartisan civil service was so great that the prohibition should remain. V. Modern Attempts at Bureaucratic Reform A. There have been a number of attempts at opening up the process of administering policy and making the bureaucracy more efficient and responsive to citizen needs. 1. Sunshine laws require agencies to conduct many sessions in public. 2. Sunset laws require congressional review of existing programs to determine its effectiveness. 3. The privatization of services occurs when the government contracts with the private sector for certain services, with the idea that some services can be provided more efficiently by private firms. This practice occurs more frequently on the local level. B. The Government Performance and Results Act of 1997 seeks to improve governmental efficiency by requiring government agencies to describe their goals and create mechanisms for evaluating whether these goals have been met. C. The Internet has also improved the efficiency of federal government. Now, citizens can find information on government websites, and can communicate directly with government offices via email. D. The Whistle-Blower’s Protection Act is an attempt to encourage federal bureaucrats to report waste and fraud within agencies. It established the Office of Special Counsel to investigate complaints about government waste or inefficiency. VI. Bureaucrats as Politicians and Policy-Makers A. Article I, Section One of the Constitution states, “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States,...” Although Congress has the power to legislate, it must rely on the executive branch to administer the laws. When Congress enacts legislation that is very precise the bureaucracy simply administers the law. However, it is rare that laws are so precise, that there is no room for questions concerning the law. When Congress passes a law that is vague in some respect, the task of the bureaucracy is to eliminate the vague portion of the law by making policy decisions. If the policy-making of the bureaucracy conforms to the desires of Congress there are only minimal problems with the process. However, when the policy-making decisions by the bureaucracy do not conform to the desires of many of the members of Congress, there are major problems within the system. B. Congress also creates enabling legislation, which delegates the power to implement legislation to agencies. Through the creation of agencies like the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Occupational Safety and Health Commission, Congressional agendas are implemented. C. The rule-making environment will also include the federal courts if a party challenges the decision of an agency or department. In deciding the case, the courts assume the decision of the executive branch is valid unless the party challenging the decision is able to prove the decision clearly violates the parameters set forth by Congress in passing the law. 126 D. In an attempt to reduce the number of court cases challenging administrative decisions, the executive branch has encouraged interested parties to participate in the drafting of administrative decisions concerning new laws enacted by Congress. This is called negotiated rulemaking. While negotiated rulemaking has not eliminated court cases of this nature, it has reduced the number of challenges to administrative decisions in certain policy areas like the environment. E. The federal bureaucracy has become a major source for decision-making concerning public policy. Since the bureaucrats have gained considerable power in this century there has been a development of considerable controversy concerning the proper role for such decision-making. An iron triangle, or a three-way alliance among legislators, bureaucrats and interest groups, seeks to make or preserve policies that benefit their respective interests. Advocates of this theory assert that there is too much influence exerted by special interests who gain the support of bureaucrats. The bureaucrats, then, no longer act as impartial administrators. Instead, bureaucrats act as agents for the special interests and attempt to influence Congress to enact laws that favor the special interest. Furthermore, the committee structure in Congress perpetuates this system. The members of Congress who serve on committees and subcommittees are interested in gaining support for their constituents who would benefit by the enactment of legislation favoring a particular special interest. F. Others assert that iron triangles do not fully describe the complex web of relations between the executive and legislative branches and interest groups. Most scholars now see the policy process as being one where issue networks dominate. That is legislators, interest groups, bureaucrats, scholars and experts and the media who share a position on a given issue may attempt to exert influence on the executive branch, on Congress, on the courts or on the media to see their policy position enacted. VII. Congressional Control of the Bureaucracy How much control of the bureaucracy Congress has is debatable. Some would argue that control of the bureaucracy is up to the president, while others contend the ultimate control is in the hands of Congress. Regardless of which view one takes it is clear that the bureaucracy must answer to both the president and Congress. Congressional control of the bureaucracy includes the establishment of agencies and departments, the budget process, and oversight conducted through investigations, hearings and review. This chapter describes the nature of the federal bureaucracy and its personnel. It clarifies the bureaucracy’s responsibilities, organizational structure, and personnel management practices. This chapter also focuses on bureaucratic policymaking and the ways in which agencies acquire the power they need in order to maintain themselves and their programs. It examines the power imperatives of the bureaucracy, and the related issue of bureaucratic accountability. The main points of the chapter are: 127 Bureaucracy is an inevitable consequence of complexity and scale. Modern government could not function without a large bureaucracy. Through authority, specialization, and rules, bureaucracy provides a means of managing thousands of tasks and employees. The bureaucracy is expected simultaneously to respond to the direction of partisan officials and to administer programs fairly and competently. These conflicting demands are addressed through a combination of personnel management systems—the patronage, merit, and executive leadership systems. Bureaucrats naturally take an "agency point of view," which they promote through their expert knowledge, support from clientele groups, and backing by Congress or the president. Although agencies are subject to control by the president, Congress, and the judiciary, bureaucrats are able to achieve power in their own right. The issue of bureaucratic power and responsiveness is a basis of current efforts at "reinventing" government. Bureaucracy is a method of organizing people and work which is based on the principles of hierarchical authority, job specialization, and formalized rules. As a form of organization, bureaucracy is the most efficient means of getting people to work together on tasks of great magnitude and complexity. However, bureaucracy can also be inflexible and wasteful, which has led to numerous attempts to reform it. The United States could not be governed without a large federal bureaucracy. The day-to-day work of the federal government, from mail delivery to provision of social security to international diplomacy, is done by the bureaucracy. The federal bureaucracy’s 2.5 million employees work in roughly 400 major agencies, including cabinet departments, independent agencies, regulatory agencies, government corporations, and presidential commissions. Yet the bureaucracy is more than simply an administrative giant. Bureaucrats exercise considerable discretion in their policy decisions. In the process of implementing policy—which includes initiation and development of policy, evaluation of programs, delivery of services, regulation, and adjudication— bureaucrats make important policy and political choices. Each agency of the federal government was created in response to political demands on national officials. During the country’s earliest decades, the bureaucracy was small, a reflection of the federal government’s relatively few responsibilities outside the areas of national security and commerce. As the economy became increasingly industrialized and its sectors increasingly 128 interconnected in the late nineteenth century, the bureaucracy expanded in response to the demands of economic interests and the requirement for regulation of certain business activities. During the Great Depression, socialwelfare programs and further business regulatory activities were added to the bureaucracy’s responsibilities. After World War II, the heightened role of the United States in world affairs and public demands for additional social services fueled the bureaucracy’s growth. Government agencies continued to multiply in the 1970s in response to broad consumer and environmental issues as well as to technological change. The bureaucracy’s growth slowed in the 1980s because of federal budget deficits and the philosophy of the Reagan administration. Because of its origins in political demands, the bureaucracy is necessarily political. An inherent conflict results from two simultaneous but incompatible demands on the bureaucracy: that it respond to the demands of partisan officials but also that it administer programs fairly and competently. These tensions are evident in the three concurrent personnel management systems under which the bureaucracy operates: patronage, merit, and executive leadership. The federal bureaucracy is actively engaged in politics and policymaking. The fragmentation of power and the pluralism of the American political system result in a policy process that is continually subject to conflict and contention. There is no clear policy or leadership mandate in the American system, so government agencies must compete for the power necessary to administer their programs effectively. Accordingly, civil servants tend to have an agency point of view: they seek to advance their agency’s programs and to repel attempts by others to weaken their position. An agency perspective comes naturally to top-level bureaucrats. Their roles, long careers within a single agency, and professional values lead them to believe in the importance of their agency’s work. In promoting their agency, civil servants rely on their policy expertise, backing of their clientele groups and support from the president and Congress. When they are faced with a threat from either the president or Congress, agencies can often count on the other for support. Institutional rivalry, constituency differences, and party differences are the chief reasons for conflict between the president and Congress over control of the bureaucracy. Because bureaucrats are not elected by the people they serve yet wield substantial independent power, the bureaucracy’s accountability is a major issue. The major checks on the bureaucracy are provided by the president, Congress, and the courts. The president has some power to reorganize the bureaucracy, appoints the political head of each agency, and has management tools (such as the executive budget) that can be used to limit bureaucrats’ discretion. Congress has influence on bureaucratic agencies through its authorization and funding powers and through various devices (including sunset laws and investigative hearings) for holding bureaucrats accountable for their actions. (See OLC graphic, "Federal Bureaucracy: The Budget," at www.mhhe.com/patterson5). The judiciary’s role in the bureaucracy’s accountability is smaller than that of the 129 elected branches, but the courts do have the authority to force agencies to act in accordance with legislative intent, established procedures, and constitutionally guaranteed rights. Nevertheless, the bureaucracy is not fully accountable. Bureaucrats exercise substantial independent power, a situation that is not easily reconciled with democratic values, particularly the principle of self-government. Efforts to reconcile the conflicting requirements of bureaucracy and democracy must take into account society’s interest in having both competent administration and responsive administration. Efforts are currently under way to scale down the federal bureaucracy. This reduction includes cuts in budgets, staff, and organizational units, and also involves changes in the way the bureaucracy does its work. This process is a response to political forces and also new management theories. The Bureaucracy The Federal government is BIG—it employs nearly 2.7 million civilian federal workers and 1.4 million uniformed military personnel. The government spends $2 trillion in fiscal year 2002. During Jefferson time just over 2000 people worked for the government. We like the countless services the government offers—postal services, national parks, food and drug inspections, federal emergency relief, so on. But we dislike the idea of too powerful and unaccountable big government and wasteful agencies full of lazy, unimaginative workers. Chief characteristics are continuity, predictability, impartiality, standard operating procedures, and red tape—time consuming, paperwork, indecisive, numerous rules and regulations. Bureaucrats career government employees, work in the 15 cabinet level departments, and more than 50 independent agencies. Embracing 2000 bureaus, divisions, branches, offices, services, and other subunits of government. 130 The FIVE big agencies—Dept of Army, Navy, Air Force (all in the Dept of Defense) the Dept. of Veteran Affairs, and the US Postal Service, tower over the others in size. Bureaucracy a rational, efficient method of organization—a body of non-elected and non appointed officials in the executive branch who work for presidents and their political appointees. During earliest years—1789-1829, the federal service in America was drawn larger from an upper class, white male elite. In 1829 Andrew Jackson called for greater participations by the middle and lower classes. He introduced what was labeled as a spoils system, which is characterized by the phrase “to the victor belong the spoils” party loyalists should be rewarded and that government would be effective and responsive only if supporters of the president held most of the key federal posts. In 1881, Congress passed the Pendleton Act (largely in response to the assassination of Pres. James Garfield) it set up a limited merit system based on a testing program for evaluating candidates. Federal employees were to be selected and retained according to their merit not their party connections. Federal service was placed under the control of a three person board Civil Service Commission (existed 1883-1978). In 1978, the Civil Service Reform Act abolished the Civil Service Commission and split its functions between two agencies. One dealt with hiring, recruiting, and promotions the other discrimination and grievances. I also created the Senior Executive Service approximately 8000 career officials filled without senatorial confirmation. Government salaries haven’t been able to be competitive to compete with private sector clubs. 131 Today Office of Personnel Management administers civil service laws, rules, and regulations (www.opm.gov) which protects the integrity of the federal merit system and the rights of federal employees. What Do Bureaucrats Do? After Congress has passed and the president has signed a bill into law, it must be implemented. Implementation of legislation is the function of the executive branch, its bureaucracy, and in some instances, state, county, and local governments. How IS the Bureaucracy Organized? Formal Organization: The executive branch department are headed by cabinet member called secretaries (save Justice—attorney general). Cabinet secretaries are directly responsible to the president. Bureau the largest subunit of a government department or agency. e.g. Bureau of the Census in the Commerce Dept, the Forest Service in the Agriculture Dept, the Social Security Administration in the Dept of Health and Human Services, the United States Mint in the Treasury Dept, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and National Park Service, Bureau of Prisons in the FBI. Government corporation Cross between business corporation and a government agency. Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation-- a cross between business corporation and regular agencies. Independent agency a government entity that is independent of legislative, executive, and judicial branch. General Services Administration, for example, operates and maintains federal 132 properties, is not represented in the cabinet, but the director is responsible to the White House and actions are closely watched by Congress. Independent regulatory board An independent agency or commission wit regulatory power whose independence is protected by Congress Office of Management and Budget -primary task is to prepare the president’s budget. It determines which programs will get more funds, which will be cut, and which will remain the same. The Hatch Act in 1939 Congress passed an act to prevent pernicious political activities (Chief Sponsor) The purpose was to neutral the danger of federal civil service from being able to shape or dictate. In 1993, Congress with the encouragement of the Clinton administration overhauled. Guidelines and Restrictions Federal officials were banned from running as candidates in partisan politics. Most could be involved in fund raisers and campaigns in some agencies (save CIA, FBI, Secret Service, and some IRS barred from all partisan activity.). Iron Triangles---see Wilson notes 133