The Necklace Affair - the royal scandal that wasn't

The Necklace Affair - the royal scandal that wasn't

The 'affair of the diamond necklace' was a scandalous event of the mid-1780s that further darkened Marie-Antoinette's reputation -- even though she was guilty of nothing and was only indirectly involved. The incident involved a grand necklace made by Paris jewellers Boehmer and Bassenge, containing dozens of multi-carat gems and a significant amount of gold (a recreation is shown in this picture, right). The jewellers had collected gemstones for years to produce this necklace, with a view to selling it to one of Louis XV's mistresses; on his death they hoped that Marie-Antoinette, already gaining a reputation for extravagance, might be the buyer. The queen was indeed shown the ornament, tried it on and was reported to be very impressed. However the asking price of 1.6 million livres (in today's currency, more than $100 million Australian) led her to decline the purchase. Legend has it that she suggested the money would be better spent on a battleship, or perhaps Louis XVI himself vetoed the sale -- but whatever the case, the Bourbons did not buy it. The jewellers then tried to sell the pendant outside France, to the various royal families and wealthy nobles of

Europe, with no luck.

In March 1784 Jeanne de Valois, the young wife of a conman, began communicating with Cardinal de

Rohan, a former Austrian ambassador and high-ranking clergyman based in Paris. Somewhat unpopular with Marie-Antoinette, de Rohan wished to obtain high office in government and he believed that winning the queen's favour was an important step in achieving this. He was convinced by de Valois that she was in frequent contact with Antoinette, and the cardinal began writing the queen long-winded letters of adulation that were promptly replied to by 'Antoinette' (in reality they were forgeries written by either de Valois or her husband). Believing the queen to be in love with him, de Rohan pushed for a meeting; de Valois organised a shadowy rendezvous between the pair in a garden at Versailles -- though Antoinette was 'played' by a

Paris prostitute who looked somewhat like the queen. Cardinal de Rohan seemed convinced by the whole charade and entrusted even more confidence in de Valois, passing large sums of money to her, ostensibly for the queen's various charities; de Valois kept the money and lived as an aristocrat for several months.

In late 1784 the aforementioned jewellers approached de Valois, also believing her to be in close contact with the queen and wishing to make another attempt to sell their necklace. Using some forged papers, de

Valois convinced the cardinal to acquire the necklace on Antoinette's behalf, with the 1.6 million livres payable in instalments. The necklace was given to de Rohan, who gave it to de Valois, who in turn gave it to her husband -- he immediately fled to England, broke up the necklace and sold its gold and jewels individually; it was never seen of again. When the jewellers failed to receive their payment there was an investigation and both de Valois, de Rohan and various other parties were arrested; after a trial that attracted strong public interest, the cardinal was acquitted and de Valois was sentenced to be whipped, branded and imprisoned for life. She escaped after a short time though (some say with the support of antiroyalist nobles) and fled to London, where she wrote sordid but fictitious accounts of her sexual relationship with Marie-Antoinette.

Most historians agree that Antoinette played little part in this imbroglio: there is no evidence of her communicating with either de Valois or de Rohan, and certainly not of any sexual affair. Despite this the

Paris crowd was eager to learn of royal scandals, and the trial created even more salacious gossip. The fact that de Rohan was acquitted suggested to many that he was knowingly set up by the queen, who evidently hated him. In the anti-royal climate of the mid-1780s the whole business created a sensation with so much mud being thrown that plenty stuck on Antoinette, despite her apparent innocence.

All tex t © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france15.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

The Diamond Necklace Affair was a scandal that was played out in Paris during 1784-5 involving a conman, his wife and an ambitious cardinal

It involved the theft of a fabulously valuable necklace that had allegedly been offered to Marie-

Antoinette, who refused the purchase

Though the queen played little or no part in this incident, her public reputation was unfairly tarnished by gossip, propaganda and innuendo

Taxation - the people's burden

Taxation is generally the burning issue in any revolution -- and things were no different in France. National debt and personal taxation were the economic crises that plagued

French leaders, who pondered how to lessen the former without increasing the latter. There was little elbow-room to do either, thanks to decades of fight-now-pay-later foreign policy. In the meantime France's people, especially the farmers and workers in the Third Estate, suffered under one of the highest-taxing regimes in Europe. The level of taxation in France was significantly higher than in Britain because

French trade interests were significantly smaller, so income from tariffs and customs duties was lower. Now, the ancien regime had reached a point where temporary measures and patch-up responses could no longer be used; a serious overhaul of the taxation system was essential.

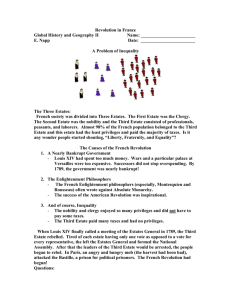

It is ironic that France decided to involve itself in the revolution in America that was sparked by unfair taxation, because the French leadership had themselves imposed an inequitable tax regime on her people, particularly those in the Third Estate who seemed to carry most of the burden (see picture, right). Personal taxes like the taille (a direct tax levied on each family, based on the amount of land owned) the gabelle (a state duty payable on salt, a valuable commodity) the capitation (a poll tax) and the vingtieme (a one-time tax to ease the state deficit) were compulsory for all members of the Third Estate -- but members of the clergy and the nobility were either exempt from these or were able to subsequently claim exemption using the parlements . In addition to state taxes the peasants were also liable for a one-tenth contribution to the church (the tithe ) as well as seigneurial dues. Meanwhile the two privileged classes managed to avoid most if not all personal taxation.

The church had a particularly light taxation burden: it paid a voluntary contribution to the state every five years called the don gratuit ('free gift') though this was neither regulated or compulsory. The nobility paid no personal taxation because it was said that, as representatives of a military elite, they paid their taxes in service and in blood.

It wasn't only that the nation's system of taxation was unfair: it was also irrational and highly inefficient.

There were many indirect taxes that had to be paid by everybody: various excises, customs duties and levies, each of which had been tacked on to revenue policy haphazardly, one after the other as the need for greater revenue dictated ... there was no single fiscal plan. And the taxes themselves were collected not by government officials but contracted 'tax-farmers', many of whom were either notoriously corrupt or hilariously incompetent. There were several attempts in the 1700s to reform the taxation system, both to make it more efficient and to allow the nobility to share some of the burden; however the parlements , which had a reputation for protecting and preserving aristocratic interests, generally proved impassable.

Louis XVI turned to successive financial ministers to solve his debt crisis but this had little impact, finally resulting in the Assembly of Notables.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france17.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

The national debt was at critical levels but increasing taxation in the current system was not an option -- economic reform was needed

The French taxation burden was shouldered by the Third Estate, with the clergy and nobility basically exempt from state taxes

The methods of collecting tax revenue were also inefficient and often corrupt, with the state paying

'tax farmers' to complete the task

Political pornography - smutty sedition

The use of pornography for political purposes dates back to ancient times, and it is still around today: pictures of George W. Bush or Osama bin Laden involved in degrading sexual acts are not uncommon.

The use of material like this was most intense - both in terms of content and quantity - during the French

Revolution. The royal family, members of the aristocracy and the government were the usual targets of these novels, pamphlets and cartoons; but minor politicians, officials, judges and soldiers could also be featured. Some political pornography could be quite mild, poking fun at individuals or caricaturing their appearance - most, however, were vulgar and demeaning, suggesting impotence, promiscuity, sexual deviancy, incest and bestiality. Marie-

Antoinette, or l'Autrichienne (the 'Austrian bitch') was the most frequent object of ridicule, followed by her husband, usually shown as weak and hen-pecked by his domineering wife. In the example shown (right) the queen is worshipping the gigantic penis of one of her lovers, probably the king's brother; the penis appears in the form of an ostrich, a play on words on

Antoinette's nationality.

Much of this material was actually produced outside of the country, mainly in England and Holland, since creating it in France would have been a serious crime

(the state operated a policy of censorship throughout most of the 1780s). Mirabeau himself spent almost a year in prison for writing satire about a high-ranking aristocrat he disliked, and there were strict sentences for those caught distributing or even just possessing this propaganda. By the mid 1780s the royal gendarmerie were fighting a losing battle however, as thousands of items of political pornography were in circulation; most examples seized by the police were logged and destroyed, but demand was too high so they were quickly replaced by new items. Some smutty stories and pictures fetched quite high prices for their entertainment and titillation value.

Some of the most blatantly falsified forms of political pornography were the libelles (French, 'libels'). These were broadsheets, pamphlets or books that purported to tell 'the true story' behind the crown, the royal family and certain aristocratic targets. They presented themselves as journalism or even as history ... and to support their claim to authenticity they were usually accompanied by excerpts of official or personal correspondence that claimed to be authentic (of course, almost all were wild invention). New libelles claimed to represent the content of a new cache of letters by or about the royals, previously unknown and acquired through an unnamed source. With no official accounts available of what transpired at Versailles, the general public lapped up this seemingly endless window into the royal and aristocratic courts.

The impact of political pornography might seem slight, but it was a significant contributor to the decline of royal authority. The circulation of this material eroded respect and affection for the royalty, particularly in

Paris, fuelling events like the women's march on Versailles. In a crude fashion it also supported the antimonarchist writings of the Enlightenment philosophes : the very concept of monarchy and aristocracy - its members engaged in decadent behaviour and sexual misconduct - was being undermined.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france13.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

Political pornography is illegal and usually false material targeting individuals, particularly royalty

It was extremely popular in the 1780s, becoming more available and more crude, especially about

Marie-Antoinette

Its impact was to reduce respect and affection for the monarchy, smoothing the path for revolutionary ideas

Revolutionary ideas

There were many revolutionary ideas that underpinned events in

France. Many of these had become popular during the

Enlightenment and had previously found voice in the American

Revolution of the 1770s; however some were unique to or emphasised more in France. The idea of equality , for example, was a direct response to the unfair social structure. Liberty, equality, fraternity became the famous catch-cry of many of the revolutionaries, but it is simplistic to leave any examination of

France's revolutionary ideas resting solely on those three.

Liberty

Members of the Third Estate considered themselves to be an oppressed group, politically, socially and legally. Though he rarely did so, the king could issues lettres du cachet upon his political opponents and imprison them without trial in the Bastille or other state prisons; feudal overlords forced peasants to leave their homes to fulfil the hated corvee (unpaid labour on the overlord's own estate or on public works such as roads); the seigneurial and ecclesiastical courts could impose the death penalty for a range of offences, without right of appeal other than to the king; torture was used quite commonly to interrogate suspects and witnesses. Yet despite this apparent brutality the people of France were, relatively speaking, better off than those in most other parts of Europe. Most historians suggest that the French Revolution was driven more by political, economic and ideological factors than a response to violent feudal oppression, yet liberty ... freedom from abuse by government and the powerful ... remained a significant ambition for many participants. Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke had expressed radical but popular arguments in favour of 'natural rights': that every person was born with the inherent right to life , liberty and property .

Equality

There is a stronger case to be made for equality. The French social structure was bitterly unfair: the first two estates were virtually exempt from personal taxation, while the nobility controlled positions of authority, ministry and bureaucracy through venality . For the rising bourgeoisie , who were eager to rise into positions of influence, this was a source of annoyance; many favoured a meritocracy where your ability, effort and talent (rather than your family or titles) determined your position in society. This was particularly true of the wealthier bourgeoisie who possessed more than the less-affluent nobility. The middle-class was also denied political representation and participation, though this was similarly true of the Second Estate.

Concepts of equality and an enterprising talent-based society were reinforced by the success of the

American Revolution and its own ideas and documents, like the Declaration of Independence. In the Third

Estate it is undoubted that many peasants, workers, artisans and sans culottes felt unfairly exploited and less than amply rewarded by their bourgeois employers. In the radical phase of the revolution the sans culottes were thus motivated by the desire for political equality (a universal franchise, not the bourgeois preferred system of 'active' and 'passive' voters) and greater economic equality, such as wage protection and price maximums.

Fraternity

Loosely described as 'brotherhood', fraternity became the third arm of the revolutionary triad. The French translation is actually egalitie from which we derive the term 'egalitarianism', meaning a belief in social, legal and political equality. Other connotations are more altruistic, such as 'concern for your fellow man' or possessed of a social conscience. Fraternity was undoubtedly expressed more in the revolution's more idealistic months, such as 1789 when the bourgeois National Assembly was churning out positive but idealistic reforms and documents like Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. As France dissolved into faction, counter-revolution, civil war and disorder, fraternity was forgotten in favour of protecting other revolutionary principles.

Popular sovereignty

This idea clearly separates feudal autocracy from representative democracy. Previously the king was

'sovereign' and was thus thought to both represent and wield absolute political authority. This idea was rigorously examined and queried during the Enlightenment, and found wanting. Philosophes like Rousseau and Sieyes suggested that the real political authority of a nation lay in the hands of 'the people', who formed a clear majority; government, kings and ministers ruled on behalf of the people, not over the people. There was no inherent authority in government, which could only stay in control while it enjoyed the support and backing of the people. The Third Estate, being by far the largest section of France's population, were the real possessors of sovereignty. Sieyes' pamphlet, 'What is the Third Estate?' articulated this idea clearly. When the Third Estate broke away from the Estates-General in mid-1789, it was a clear sign that they had accepted this idea as fact.

Constitutionalism

When the Third Estate separated from the Estates-General and met to swear the Tennis Court Oath, their pledge was to remain united until France had a constitution in place. Their desire for a written political framework was no fluke: it was based on the success of the Americans and their own written constitution, and marked a decisive turning-point in the relationship between governments and the governed. Fed up with the whims and broken promises of kings and ministers, many wanted a legislated written framework that clearly articulated the extent and limits of power. Almost all nation-states today have constitutional documents that underpin their governmental structure (only Great Britain, New Zealand and Israel do not, although their 'constitution' is said to be written in common law, precedent and convention). Constitutions protect the people from the excesses of rulers, articulate exactly what government and its offshoots can and cannot do, are rigid enough to provide stability but also flexible enough to be changed when the situation demands. Of course it could be said that France's constitutionalism was a failure, because the nation has had a dozen different constitutions since 1789, including three during the revolution (1791,

1793 and 1795).

Property

'Life, liberty and property' were the three 'natural rights' espoused by Enlightenment philosophers such as

Rousseau and John Locke. As far as property goes, this was the undeniable right to acquire wealth, land or possessions through one's own efforts, and to keep them safe from theft and seizure. The bourgeoisie who dominated the National Assembly of 1789-91 demonstrated strong interests in protecting and enhancing their capacity to acquire property: the Constitution of 1791 banned guilds and workers' associations, restricted the franchise (right to vote) to a much smaller 'propertied' class, and stabilised economic conditions and procedures. Other reforms, such as the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, also benefited the bourgeoisie , albeit indirectly (e.g. the sale of church lands).

Religion

Religion became a battleground of the revolution, particularly after 1789. Religion had previously been a focus for the philosophes, particularly Voltaire, who criticised the excesses and profiteering of the church and the higher clergy. The bourgeois National Assembly proclaimed freedom of religion where it didn't impact on 'public order', and in 1790 launched an amazing attempt to create a virtually nationalised

Catholic Church by setting and paying wages, declaring clerical appointments by election, and compelling all clergy to swear an oath of allegiance to the state. Church lands were confiscated and sold, the profits going to the state but the lands (not surprisingly) purchased by bourgeois speculators. These attacks on the church, which would have been unthinkable only two or three years earlier, divided the revolutionary cause instead of drawing more followers to it. The conservative, faithful peasantry in some areas even responded with counter-revolutionary violence (eg. the Vendee in 1793). Atheism, a fascination with classical mythology and Robespierre's rather bizarre 'Cult of the Supreme Being' all alienated many

French from the revolution.

The seigneurial system - a little bit of feudalism

Feudalism as you may know the term emerged in the

Middle Ages and became the dominant social structure throughout Europe: the feudal hierarchy determined the relationship between monarch and nobles, set in place an economic system and enabled Europeans to co-habit and survive in small communities. By the 1700s there were still aspects of feudal practice in French society but feudalism as a system had lost its importance, at least to the national government and the broader economy, which by then was largely capitalist in nature. What remained in rural areas was the seigneurial system, a form of feudalism that while not nationally significant still impacted on the lives of the peasantry.

In this watered-down form of feudalism, the seigneur ('lord', in practice the land owner) generally rented out certain sections of his estate in small plots to individuals or small groups. Those who lived and worked on the seigneur's land were subject to a range of quasi-feudal taxes or requirements. The land-owner could hold a seigneurial court within his estate and could therefore pass legal judgement on peasants who lived there; there were over 70,000 of these courts in place. The seigneur could extend a monopoly over the flour mill, the baker's oven and the grape press (all critical infrastructure in a village) and demand taxes for their use. He could demand seigneurial dues such as the quitrent or the champart (requisitioning of a certain amount of produce). The seigneur could also demand the much-loathed corvee , which required each peasant to complete labour on projects belonging to the seigneur, such as building or repairing his house, fences or bridges (the corvee was unpaid and often demanded at short notice).

It was not just the nobility who could be seigneurs: in fact many members of the clergy and the bourgeoisie purchased seigneuries through the 17th and early 18th centuries. Many were attracted by the status symbols and the trappings of being a seigneur: exclusive hunting rights, an individual pew in the local church and so forth. The seigneurial system came under attack throughout the 1700s though, many of the philosophe intelligentsia commenting that many peasants existed as virtual slaves. Some radical economists suggested that the seigneurial system held back production and that a more open labour market would aid progress. The legislation and paperwork involved in maintaining such a system was also extensive and complex. Despite these criticisms, the seigneurial system and its semi-feudal practises did not undergo reform until the peasants took matters into their own hands in 1789.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france5.htm.

Today's date (last access)

Key points:

The seigneurial system was a derivation of the old medieval feudal system and remained in place by the 1780s

Seigneurs were land-owners who retained extensive rights and privileges over those who lived on their estates

This system was unfair and exploitative, and was much criticised by both the philosophes and the peasantry

Voltaire - a thorn in the ancien regime

Voltaire was the penname of the French writer François-Marie Arouet, who lived between 1694 and 1778.

Born into a moderately wealthy family, the son of a government official, Voltaire received an education in

Greek, Latin and law from the Jesuits. He was a free-spirited character even when young: at age 20, while working in Holland, he attempted to elope with a young French emigre (their plot was discovered by

Voltaire's father, who ordered him back to France). After arriving back in Paris he spent a year imprisoned in the Bastille for writing satirical poems about members of the aristocracy. After his release Voltaire continued to write undaunted; in 1726 he was forced into exile after a lettre de cachet was issued against him. During Voltaire's three years in England he engaged in study of the English political and judicial

systems, considering it to be more advanced and respectful of human rights than those of France. In 1729 he published Philosophical Letters on the English which caused considerable controversy in France.

One of Voltaire's strongest beliefs was also the need for religious tolerance. Throughout his life he was a fierce critic of the endemic corruption present in the Catholic church, particularly among high-ranking clergymen such as canons, bishops and archbishops. He wrote plenty about the disproportionate landownership of the church and the large tithes it imposed on the peasantry. He commented on how wealthy aristocrats bought positions in the upper clergy and of the interference of Rome in local and regional church affairs. He was not anti-religious however; though often accused of being an atheist (an insulting slur at the time) Voltaire often proclaimed belief in a higher being; he was, more correctly, a deist: one who believes in a non-interfering God.

Rousseau - the revolution's political inspirator

Like Voltaire, Rousseau was an Enlightenment philosopher whose political and philosophical ideas contributed to the French Revolution.

Also like Voltaire, Rousseau was dead before the revolution began (he died in 1778) but his works were well-known in France throughout the 1780s. Born in Switzerland, Rousseau was an avid reader but had little formal education, instead completing apprenticeships to a government official and an engraver. Travelling to Paris, he later befriended fellow philosophe

Denis Diderot and had an article published in

Diderot's famous Enlightenment work

Encyclopédie.

Rousseau pondered a simple question: "Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains..." - why do people submit themselves to the rule of kings and governments? He explained it by suggesting that humans are essentially good and desire similar things, including peace, stability and good order. Nature, however, is brutal and when left to their own devices all creatures - man included - will descend into savagery. Consequently, civilised human society cannot exist without a series of laws to keep order. Governments pass these laws and people who wish to live in a peaceful society agree to follow them. It is the responsibility of governments, therefore, to protect the people; governments, kings and ministers do not simply exist to serve themselves.

Rousseau's "social contract" (the unwritten agreement between governments and individuals) and his concept of popular sovereignty (the power of government being derived from the consent of the people) were core ideals in both the American and French revolutions. Political thinkers in each of these revolutions adapted Rousseau's ideas and followed his precept that political systems, though never perfect, should continue to develop and improve. Radicals also empathised with Rousseau's claim that private property was an impediment to good political leadership, as the protection of property interests often distracted politicians from their true role of representing the people and ensuring morality.

His views on religion also influenced the course of the revolution. Rousseau's belief that there should be a

"civic religion", a state-based religion to protect political morality rather than to serve the interests of the church, was controversial - but it also informed measures like the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the

bizarre new regime movements, the Cult of Reason and the Cult of the Supreme Being. There was also a form of cult built up around Rousseau himself as the picture (right) suggests. Among the revolutionary or

Enlightenment symbols shown are the fasces (representing power) the Phrygian cap (liberty) the cornucopia (plentifulness) the olive wreath (peace) and the all-seeing eye (a vigilant God).

Salons and clubs - nurseries of dissent

Today a salon is somewhere you go for an expensive haircut - but in 18th century France it served a completely different purpose.

Hosted in private homes, usually in libraries or drawing rooms but sometimes in bedchambers, the pre-revolutionary salon was a gathering of the informed, the educated and the intellectual for intelligent discussion. Usually focussed around one person, often the host but sometimes a newcomer or an invited guests, the attendees would discuss issues of the day and quote from recently-acquired classical texts. One of Madame de Stael's salons, held in her garden, is shown in the picture (right). As the

1700s progressed and the Enlightenment philosophes became popular, the talk in salons became increasingly critical of the government and the royal family. They also involved less informal dialogue and more reading and writing of letters and documents.

The American Revolution and its core documents - such as the

Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of

Rights - saw heightened activity in the French salons.

What is unusual is that many salons were actually dominated by women; many of the leading salons were hosted by notable women, such as Madame Roland, Madame de Stael and the wife of Jacques Necker. For the men, there were cafes and cercle . The affluent men of Paris preferred the fashionable and lively cafes - not that dissimilar to today's cafes - as their meeting-place for discussion and debate. The cercle was a casino-type club for the provincial and rural bourgeoisie . Though less trendy and distinctly more pleasure-centered than the salons and cafes, they also served as a venue for distributing and sharing liberal and revolutionary ideas. Political pornography was often revealed and discussed in a cafe or cercle, suggesting a macho rowdiness that was obviously lacking in noble and bourgeois salons.

Though these places did not constitute cohesive revolutionary groups, they certainly provided a basis for criticisms of the ancien regime and liberal Enlightenment ideas to emerge, develop and spread. Their role in organising like-minded people was an important precursor to the political clubs of the 1790s; the

Girondinists, for example, emerged from the Cercle Social, one of the largest such gatherings.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france12.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

The salons were gatherings of individuals, mostly women, who considered themselves intellectual and informed

They discussed current issues and events, as well as literature, philosophy, art and other cultural topics

The men usually gathered in a cafe or cercle, which were less formal and more rowdy, but served a similar function

Compte Rendu - Necker cooks the books

In 1776, the king appointed Jacques

Necker as finance minister of France.

Though of Swiss background and

Protestant by religion, Necker had shown great talent in managing the affairs of the French East India

Company - and his influential wife had been lobbying actively on his behalf.

He continued to demonstrate potential after his appointment, though his main skill was acquiring loans and juggling debt rather than economic management and reform. Necker's ability to manage the deficit was tested by France's involvement in the

American Revolution from 1778 onwards, which would cost the nation more than 2 billion livres. He managed to fund the war effort but, again, it was through borrowing at rates of high interest, rather than by raising state taxes or revenues.

By 1781 disaster was looming as the nation was approaching bankruptcy. Necker produced a document that was stunning in its deceit: the Compte Rendu du Roi (loosely translated, the 'king's balance sheet') was a statement of the nation's financial situation (see picture, right, which reads "Necker takes the measurements of France"). However the Compte Rendu suggested there was a fiscal surplus rather than a massive debt . The publication of the glowing numbers of the Compte Rendu earned Necker hero-status amongst the people; he was hailed as an economic miracle-worker, despite being no such thing. The document concealed the disastrous level of debt and would make subsequent attempts at taxation reform more difficult than they would ordinarily have been. Thus the Compte Rendu du Roi was not a revolutionary event itself but it certainly contributed to the crises of the late 1780s.

Despite his popularity with the people, Necker was despised by Marie-Antoinette. After attempts to curtail spending and push through reforms failed later in 1781, he was dismissed, probably at Antoinette's urging.

After his two successors, Calonne and Brienne, both failed in their own attempts to achieve reform, Necker was recalled by Louis XVI as minister of state. It was Necker's advice that the Estates-General be summoned to ratify economic reforms. More court intrigue led to his second dismissal, this time on July 11,

1789. The Paris crowd, incensed at the news of Necker's sacking, stepped up their violence and attacked the Bastille.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france20.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

Necker was finance minister between 1776-81 and then again in 1788-89

In 1781 he released the Compte Rendu , a positive but dishonest report on the financial state of the nation

Popular for the Compte Rendu and his attempts at reform, the sacking of Necker in 1789 provoked unrest in Paris

French government - rule by royal court

To understand the problems Louis faced as king it is necessary to understand the nature of

European politics at the time. Many nations possessed near-absolutist monarchs in the late 1700s but they generally shared power, willingly or otherwise, with a noble or aristocratic class. This wasn't always an amicable relationship: many nobles manipulated, pressured or bargained with the monarch to secure power and influence for themselves. In Britain this relationship had been formalised and consolidated by longstanding agreements between the monarch and aristocracy (eg. the Magna Carta, 1215) and the power of parliament was consolidated by events such as the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution. The British king still had significant power but took care not to assert it too eagerly or autocratically. In France, Louis' royal power was still nominally absolute.

The French political model had been shaped by the reign of Louis XVI's great-grandfather, Louis XIV, during the late 1600s. As a child of nine this particularly Louis was driven from his palaces by a bitter civil war instigated by the nobility and Paris parlements, against the crown and its ministers. Louis XIV's response was to assume absolute control of the government. The king justified this by proclaiming his rule was given by 'divine right', with the support of God (when asked by a political emissary what comprised state sovereignty in France, Louis' reply was: "Le t'at? C'est moi!" ('The state? That's me!'). The nobility was considered a potential danger to the monarch and its power and influence was drastically curtailed... not only that, Louis believed the aristocrats must be carefully watched and, if possible, controlled. To reduce their influence and their capacity to organise military opposition, Louis XIV based the government at the royal palace of Versailles, outside Paris and required the almost permanent attendance of the nobility. There they would spend their days seeking Louis' acceptance and patronage, engaging in almost pointless court intrigues as well as gambling, hunting, balls and sexual affairs. Kept away from their traditional support base on the estates, the nobility became virtually powerless. In the extravagant mini-city of Versailles, with its 700 rooms and 20 miles of roadway, the Sun King ruled France in virtual isolation from the people but with a close eye on those he saw as his biggest threat (a living embodiment of the epithet 'keep your friends close and your enemies closer').

This tactic may have strengthened the monarch's hold over the nobility but it also isolated him from his subjects. Before the reign of Louis XIV the king had been a mobile and rather visible presence in France; now he was a figure of myth and speculation, isolated at Versailles and rarely seen. The strength of

French autocracy was really underpinned by the strong personality of Louis XIV but his predecessors, particularly Louis XVI, were neither interested in or capable of maintaining their control of the nobility through strength of character and court intrigues. In addition, during the reign of Louis XVI the

Enlightenment trend of questioning the nature of politics, the function of government and the basis of political power was well established. These philosophes looked at the natural order and using reason instead of tradition, they could find little evidence to support divine-right absolutist monarchy. The nobility, aware of the declining authority of the king, resisted his policies and reforms during the 1780s, partly because they genuinely disagreed but also as a means of eroding the king's power and increasing their own. And from within French society came calls to recognize and formalize the political voice of the Third

Estate, which made up 97 percent of the population but was denied representation or participation in government. It was a situation few, if any kings could have found effective solutions for.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france7.htm.

Today's date (last access)

Key points:

French government was centred around the king, shaped by the autocratic rule of Louis XIV, the

'Sun King'

The king remained at Versailles most of the time, a central figure in the court of royalty and nobility

Louis XVI lacked the character and personality to impose absolutist rule, at a time when circumstances were dire

Harvest failures - starvation and speculation

As in many other revolutions, food shortages, high prices and hunger formed a volatile social backdrop to the French

Revolution. The French people were no stranger to hunger, however. The labour intensive, semi-medieval methods used by most peasant-farmers meant inefficient production; and it also rendered them susceptible to variations such as pestilence and the weather. The majority of people were generally able to cope with this; in times of poor production and low grain storage they simply ate less, or foraged for alternative food sources. At the outbreak of the revolution, however, they had endured a horror year in terms of food availability and prices - and another similar year looked to be coming.

France endured extremely poor harvests in 1769, 1776 and 1783. The harvest of 1788 was decimated by a freak hailstorm so the crop yield was poor; this meant that the granaries were less full during the bitterly cold of 1788-89, and there was less seed for planting in the spring of 1789. Limited harvests meant that grain, corn and vegetables were sold to whoever could afford to pay the highest prices; in most cases this was in the more prosperous cities and regions, leaving the poorer ones short of food. In Paris, a fourpound loaf of bread rose from 8-9 sous to 14-15 sous in February 1789; it would remain at this level until after July. In addition to the bread crisis there were also problems in secondary markets: property rents, which had been rising since the 1750s, again spiked; there was a series of livestock epidemics that led to a shortage of meats; the silk harvest of 1787 failed. The skyrocketing rise in bread prices had a knock-on effect to other industries too. As members of the Third Estate had to spend more and more of their income on bread -- up to 80 percent in some cases -- they had less to spend on products made by artisans: clothing, tools, furniture and so forth. These workers also began to lose money.

Since speculation about the availability and the price of food was usually informed by future harvests as well as past ones, the people of France had good reason for concern about the winter of 1789-90. Events like the Paris revolt and the Great Fear were consequently motivated as much by panic about the future as conditions in the present. One unusual theory proposed suggests that the poor harvests prompted farmers to sell grain infected with ergot, which they would not have ordinarily done; since ergot has distinctive hallucinogenic properties similar to LSD this may have been an additional factor to the behaviour of some individuals during the Great Fear.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france19.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

French peasants were no stranger to food shortages but 1788-89 were two years of real and envisioned hardship

What little grain there was found buyers in the wealthier cities and regions, while others went hungry; prices consequently skyrocketed

This inflation had flow-on effects in the French economy and by mid-1789 there was paranoia and urgency for some kind of solution

'Dangerous Liaisons'

A short book appeared in France in 1782 that added to the ongoing portrayal of the aristocracy as decadent, cruel and perverse. "Dangerous

Liaisons" (in French, Les Liaisons Dangereuses ) was a novel told as a series of letters between the main protagonists, the conniving Marquise de

Merteuil and her former lover, the playboy Count de Valmont. Purely to relieve their boredom, two agree to engage in a long-running game of intrigue, manipulation, sexual conquest and negotiation involving a range of other aristocrats. De Merteuil, who harbours a grudge against another count, de Gercourt, wishes de Valmont to seduce his young fiancee, thus denying de Gercourt her virginity. De Valmont, however, wishes to seduce a virtuous married woman and convinces de Merteuil to enter a bet: if he can provide proof of this seduction, de Merteuil will once more sleep with de Valmont.

Numerous criticisms of the aristocracy were represented in "Dangerous Liaisons". The idleness of the main characters and their subsequent boredom led to decadence and immoral behaviour; there was already an exaggerated belief that the rich nobility had little to do except conduct intrigues and affairs, a belief reinforced by this book. The main characters use religion in a cynical manner, particularly de

Valmont, who feigns religious piety in order to sexually pursue his married victim. The letters reflect a disdain for the lower-classes, the servants and the bourgeoisie . Above all the aristocrats in the book have little or no sense that they are or should be contributing to society; their lives are wholly concerned with the exploitation and denigration of others, including those of their own class.

There were many similar books, plays and pamphlets that appeared in the 1780s, many with more blatant sexual content, however "Dangerous Liaisons" remains one of the most enduring works of the period.

Numerous film versions have been made, the best-known being the 1988 movie starring Glenn Close,

John Malkovich and Michelle Pfeiffer (see picture). The 1999 film "Cruel Intentions" was loosely based on the novel, Sarah Michelle Gellar and Ryan Phillippe portraying the characters of Merteuil and Valmont respectively.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france16.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

"Dangerous Liaisons" appeared in 1782 at a time when criticisms of the ancien regime were growing

It tells the story of two aristocrats who spend their days engaged in sexual intrigue and manipulation of others

It popularised the notion that the aristocracy were lazy, big-spending trouble-makers serving no function in society

Reveillon riots

These riots pre-dated both the Estates-

General and the assault on the Bastille, so they demonstrate well the potential for violence, particularly amongst the Paris crowd. The incidents were centred around a

Paris factory owner named Jean-Baptiste

Reveillon, who manufactured expensive wallpaper for nobles and wealthy bourgeoisie (rumour has it he also supplied the royal family). His factory employed about 300 workers. In April 1789 with food shortages beginning to bite, Reveillon made a speech suggesting that bread prices should be frozen or even cut, to alleviate the suffering of the poor. His benevolent comments were misinterpreted as a suggestion that wages should actually be cut, prompting hundreds of angry Parisians to march on his factory.

Once there they found it under the guard of a few dozen troops, however the following day the mob returned and destroyed both the factory and Reveillon's house (he and his family managed to escape over a garden wall). The picture, right, is a contemporary representation of their looting. The crowd also went on to destroy a second factory, owned by another businessman who they believed to have made similar comments. More than 20 people died in the riots as the Paris Guard (an early armed police force) fired on looters with guns and small cannon. According to one eyewitness, the riots were supposedly about food prices but other factors may have been at work. His summary also suggests that there was tension between the Estates on the eve of the Estates-General:

"The pretext is the high price of bread but this is less dear in Paris than it is in the provinces. The Estates-

General will be stormy. There is great ill feeling between the orders. A great many people have been arrested. Yesterday the king issued an edict bringing guilty persons within the jurisdiction of police courts.

The parlement behaved as it always does: slackly. A few unfortunate rioters were found dead in

Reveillon's cellars... they had drunk varnish and raw alcohol, thinking it to be brandy." (Marquis de

Ferrieres, April 30, 1789)

Reveillon himself fled to England, where he re-established his business, to the extent where it was producing 'patriotic wallpaper' (in red, white and blue with revolutionary motifs) and exporting it to France throughout the revolution.

All text © Steve Thompson 2006

To reference this page: Thompson, S. vcehistory info (Internet) at http://vcehistory.info/france/france24.htm. Today's date (last access)

Key points:

The Reveillon riots were one of the first examples of revolutionary violence in Paris in 1789

Reveillon was a wallpaper manufacturer who was rumoured (incorrectly, as it turned out) to have suggested cutting wages

A large crowd looted and destroyed his factory and his home, before being confronted by the Paris

Guard

The Diamond Necklace Affair

How did the French Revolution begin? With the fall of the Bastille. Similarly - How did the American Revolution begin? - With shots fired at Lexington and Concord.

Those are the stock answers, but neither marked the first act of open defiance against the crown. Americans would say the Boston Tea Party or Boston Massacre or Stamp Act riots marked that.

Same for the French Revolution. Frenchman may say the erosion of royal authority that overthrew France's social order began with the Estates General in 1789, but before that the first event to both rock the foundation of

monarchy and also display open defiance of royal authority was the "Diamond Necklace Affair" or the"Affair of the

Queen's Necklace".

The Story

This article retells that story. This story that launched the French Revolution was one of the most notorious public scandals of history. It involved great fortunes made and lost, of avarice, mystery and intrigue, it pits great forces in

French society against each other, but in the end severely damaged the monarchy to the great detriment of both, and destroyed for all time the reputation of the second highest public figure in the French monarchy. The story starts with three players; the first is that famous public figure - the Queen of France: Marie Antoinette. This story had its root cause, its currency and appeal from this most star-crossed figure of French history.

The Queen

Marie Antoinette was an Austrian Princess when she came to France, at age 15, in 1770, to marry the Crown Prince.

She and husband Louis XVI were still teenagers when they ascended the throne in 1774. Unlike her shy awkward husband, Marie Antoinette was admired for her legendary beauty, grace and elegance and her tastes which set fashion trends for Europe. She took pride in her appearance and in her ancestry as a princess of Hapsburg, the oldest royal house of Europe. Her arrogance brought resentment from old nobility of France, a country which had been at war with Austria for much of the 18th century. Marie Antoinette also attracted gossip for her inability (due to Louis's impotence) to become pregnant and produce an heir to the throne, for her youthful disregard of court etiquette, and for her frivolous and costly lifestyle. This lifestyle included gambling, masked balls, late night rendezvous and rumours of her having had numerous love affairs with both men and women. Even by 1785, an underground literature existed that reviled the Queen in pornographic songs, pictures and pamphlets.

Much of Marie's fast and loose behaviour in her first decade in France was a reaction to her marital frustration; but in 1778, Louis had an operation and the couple at last had children. By 1785, Marie Antoinette had given birth to three children. She was maturing and her lifestyle had grown far more sedentary and less extravagant. But that change was hardly noticeable to the uninformed public and did little to assuage those who had already developed their dislike for her.

The Nobleman

Against this backdrop in 1784, enter the two key players in the story - one, a great nobleman, the other, a woman swindler who dupes him. The nobleman Louis René Édouard de Rohan was Cardinal of France and son of one of its oldest and most famous noble houses. However, Rohan had a problem. He was in disfavour at the French court. The

Queen's mother Marie Thérèse did not like Rohan, frivolous dandy, when he served as a diplomat to Austria. After her mother scorned him, Marie Antoinette refused to receive Rohan and had not even spoken to him for a number of years. For 10 years, Rohan had longed to become a member of the Queen's close circle, with the new favours and patronage that could bring. Rohan, the dandy, was also attracted by the Queen's beauty and fancied that if she would only admit him to her circle, he too might partake in her amorous favours, of the type frequently rumoured in court.

The Swindler

The woman swindler is the Countess de Lamotte. She was the daughter of the old and famous Valois family, but the family has long lost its resources. She was quite impoverished when she arrived in Paris. But Lamotte was also quite attractive and brazen in her desire to escape poverty and obtain an aristocratic life of comfort and leisure. She sought to enlist the sympathy of the royal court in the fate of a woman from one of France's old houses. She was given to fainting spells at court and in doing this has at last receives notice from Madame Elizabeth, the King’s sister who provided her with some funding. She was also noticed by Cardinal Rohan. By 1784, she had become his mistress. Even though she had not succeeded in obtaining the interest or support of the Queen or even met the

Queen, Lamotte succeeded in convincing Cardinal Rohan that she has the favour of Marie Antoinette. Rohan fully subscribed to the tales in court circles of Marie Antoinette's sexual dissipation. Using her full figure and attractive

looks to great effect, Lamotte spun stories that convinced Rohan that she, Lamotte, was becoming one of the

Queen's new lesbian love interests, just as Rohan hoped to become her lover as well.

The Necklace

Now enters the object all seek - the necklace. The necklace was 2800 carats. First was a choker of seventeen diamonds, five to eight carats each; from that hung a three-wreathed festoon and pendants; then came the necklace proper, a double row of diamonds cumulating in an eleven-carat stone, finally, hanging from the necklace four knotted tassel. It cost 1,600,000 lives. Perhaps in today's currency, this is the equivalent of $100 million. The jeweller Charles Bohmer had the beautiful necklace made for Madame du Barry. But Louis XV died, du Barry was banished from court, and Bohmer placed his hopes on the new Queen to purchase the necklace. She modelled it before her ladies, but would not purchase it or permit Louis to buy it as a gift for her. "Better to buy a new ship of the line (battleship or aircraft carrier equivalent) than to spend such a sum on a necklace, regardless of how beautiful ..." she said.

The Opportunity

Boehmer too had seen Lamotte at court. Like Rohan, the jeweller too believed the Marie Antoinette rumours at court. The jeweller appreciated Lamotte's looks, believed she had the Queen's favour and sought her out as an intermediary. Knowing Rohan's keen desire to obtain the Queen's favour, Lamotte saw her opportunity to trade on the belief of both men in her intimacy with the Queen to satisfy the desires of both men and enrich herself. She told the cardinal that the Queen wanted him to secretly purchase the necklace on her behalf. The cardinal obtained the necklace from Bohmer and gave it to Mme Lamotte, expecting the Queen to pay for it. Of course, Marie

Antoinette never saw the necklace. Lamotte gave the diamonds to her husband, who took them to London and sold them. Lamotte forged letters from the Queen to Rohan attesting to her interest in the necklace, approving the plan and Lamotte's role, and indicating Rohan could expect return to the Queen's favour

The Rendezvous

The letters satisfied Rohan for a time, but at Versailles, Marie Antoinette ignored Rohan as always. He wanted a real sign of her interest in him. Rohan needed more and it was at this moment in the gardens of the Palais Royal in

Paris the final piece to her puzzle fell in place. It came in the from of a 25-year old streetwalker, Madame d'Olivia, buxom and blonde, with an arrogant strut, such that people called her "Queen". Lamotte was at once captivated by the young d'Olivia's striking resemblance to 29-year old Marie Antoinette. And so, Cardinal Rohan did get the sign of favour he wanted from the Queen... or so he thought. On a summer night in 1784, Lamotte outfitted the woman in a lawn dress, the same as the famous Marie Antoinette "en gaulle" painting then on exhibit. The veiled woman briefly met the Cardinal in the gardens of Versailles, late at night as Antoinette was rumoured to meet her lovers.

The false Queen gave the Cardinal a rose. She said, "All may be forgiven ..." and hurried away, leaving the Cardinal under the illusion that he had met Marie Antoinette.

The Confrontation

Unaware of the real drama unfolding, Marie Antoinette was busy preparing herself for the part of the saucy barmaid

Rosina in the controversial play Marriage of Figaro. On the day of one her rehearsals Boehmer's invoice for the necklace arrived and was discarded by the Queen. Later, Bohmer came to Versailles and spoke to the Queen's servant Madame Campan, seeking payment. He displayed forged letters signed by her, and told how Rohan was involved in acquiring the necklace. At last, Marie Antoinette realized the serious of the case, and summonsed

Bohmer to Versailles. She was furious with Rohan, so was Louis XVI. The royal couple demanded a trial. They arranged for the arrest of the Cardinal, the highest clergyman in France, in the most public way, handing him the arrest warrant in the great hall of Versailles with hundreds present. He was brought before the King and Queen, who confronted him with the swindle and would hear none of his professions of innocence and that he too had been made the fool.

The Trial

The public arrest of the Cardinal of France had already caused a national sensation, and the acts of King and Queen that followed added new fuel to the fire of public interest and imagination. That this nobleman with whom she had not spoken a word in 15 years would dare to presume that she, Marie Antoinette, would meet him at a secret rendezvous, was a serious insult to her name and reputation. The proud Queen demanded public vindication of her good name. The matter could have been handled quietly at the court or by the Vatican. Louis's advisors suggested caution, but the wavering King agreed to a public trial before the Parlement of Paris. France of 1785 was not used to such public events. While rumours of Marie's errant behaviour were prevalent in the capital, they now became sensation for all of France. The charge against the Cardinal was lese-majeste, insult to the dignity of the Queen.

For months, the nation was gripped by the mystery of the diamond necklace and the recounting of the Queen's reputation that led Rohan to believe she had participated. The public was riveted by the accounts and characters, the swindler Lamotte, the prostitute who impersonated the Queen, the $100 million necklace at stake at a hard time when the country faced bankruptcy. Through it all, Lamotte held to her story that the Queen was behind it all and had the necklace.

The Verdicts

The case to defend the Queen's dignity would never have been easy. Though she never appeared, this case put the life of Marie Antoinette was on trial. Many jurors could believe based on her past spending and loose lifestyle that

Marie Antoinette was capable of these activities and that the Cardinal was reasonable in his beliefs. The Cardinal struck a sympathetic figure as he pleaded his devotion to the Queen and that he only sought to serve her. But this was no ordinary court, it was a court of nobles in Paris, where Rohan was a great and wealthy family, where many had been at odds with the King and many more still resented the Queen. Add to that considerable sums were passed in bribery by the Duc of Orleans and other disaffected noblemen. The trial ended with the Cardinal acquitted of the charge of lese-majeste. Lamotte was found guilty as a thief and imprisoned. She was also publicly flogged, and branded. As she struggled against the branding iron, the poker slipped and impaled her breast. Lamotte hurled imprecations for all to hear: "It is the Queen who should be branded not me!"

The Uproar

The night of the verdict, against constable's advice, Marie Antoinette attended a charitable benefit at the Paris

Opera. When the verdict "Rohan Acquitted" was announced, the opera house erupted with applause. The crowds then whistled and hooted at the Queen, who left in dismay to weep at Versailles with her ladies in waiting.

Repudiation of a French sovereign by court verdict and public rebuke had never before occurred. The Revolution had now begun. Within the year, Lamotte escaped to London. With her husband they enjoyed the money from the diamond necklace, now broken up, but she also took to the quill to spread malicious rumours about Marie

Antoinette.

The Libels

Pamphlets by Lamotte of new stories of Antoinette's sexual appetites and orgies at Versailles, and her claimed love letters between Rohan and the Queen became a new sensation in France as they were smuggled in by the thousands. The court literature against Marie Antoinette in the capital, by virtue of the necklace case, had now become commonplace throughout France. The economic position of the country worsened and King Louis, who drew closer to Marie in her sorrows, increasingly turned to her for advice in economic matters. The Queen's increasing role and national disgrace weakened the position of Louis and the monarchy. Her presence galvanised and emboldened the opponents of the regime.

The Revolution

Revolution could have been averted in France after the necklace case, just as it could have been averted in

America after the Boston Tea Party, but a course of action had been set in motion. The monarchy was humbled by the noblemen in court and people, all done with impunity. Going forward, the opponents of the regime, first among the nobles, later among the merchants, finally in the peasantry took heed and didn’t let up until the final violent overthrow of the French monarchy and the Terror among its citizens that followed. The nobles who sought to check

Louis's power and others like Phillipe Egalite who resented the King, came to be caught up themselves in the

whirlwind of Revolution. That Revolution would claim the lives of thousands of nobleman including Phillipe, and end the privileges nobles had held in France. This was not what the nobles intended when they sought to vindicate

Rohan and strike a blow against the King and Queen.

The Reversal

When Marie Antoinette learned of the necklace affair, she instinctively insisted on a public trial to avenge the offence to her honour and dignity. No one could have imagined how her act of hubris would trigger the catastrophic upheaval of Revolution in the 7 years that followed. In 1786, Madame Lamotte was imprisoned and branded; Rohan was acquitted at trial but forced from his Cardinal post to a remote posting. Marie Antoinette sat on her throne, still the glamorous powerful Queen of France, meeting out punishment to those who dared transgress her honour. In

7 years time, the Revolution would reverse the positions of the three players in this story. In 1793, Lamotte who had escaped her prison lived in comfort in England. The fortune she and her husband shared from the necklace was enhanced by the amounts made from the sales in France of her best-selling pamphlets against the Queen. Lamotte had become a hero of the Revolution. In 1793, Rohan too was living in comfort in exile. In the early years of

Revolution, he returned in triumph and was elected to the Assembly. But Rohan saw the violent turn of revolution against the nobility and clergy including his family. Rohan escaped France to live out his life in a comfortable exile.

The World Upside Down

In the ultimate role reversal, the hunter became the prey. 1793 saw the final destruction of Marie Antoinette - humbled, humiliated and finally beheaded by her own subjects. The years of Revolution took everything away from

Marie - her palaces, her jewels, her servants, her fine clothes, her friends and her family. Gone was her beauty and finery in which she took such pride and all the other trappings of her once fabulous life. In the end, Marie

Antoinette was alone. She was taken from her prison cell, as a poor broken widow in her rags, old before her time.

Now, it was SHE who would be the prisoner in the dock. SHE would have to answer the charges of the revolutionary tribunal, including the necklace case allegations of Madame Lamotte.

The Queen Beheaded

These charges still rang in her ears in the jeers of the crowd as Marie Antoinette road to her date with Madame

Guillotine. The former Queen now road in an open cart, her hands tied behind her back, and held in tether like a chained dog. Lamotte must have relished the irony that 7 years after she was flogged, branded and humiliated, 7 years after Lamotte swore vengeance, it was the turn of her tormentor to face punishment - Marie Antoinette was beheaded at age 37, her fair head held high for the populace to cheer her death. Such was the pendulum swing of great French Revolution, first set in motion by the case of the Queen's necklace.