Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration, (I), AIR 1978 SC

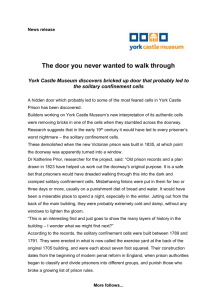

advertisement