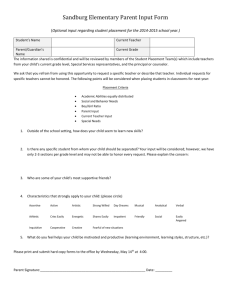

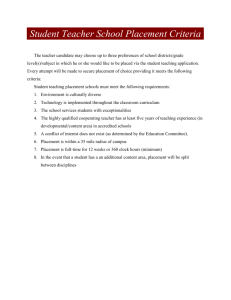

Rationale

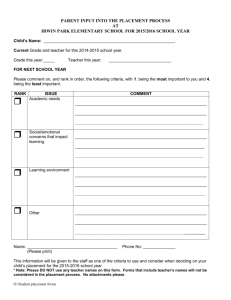

advertisement