Blanchard4e_IM_Ch05

advertisement

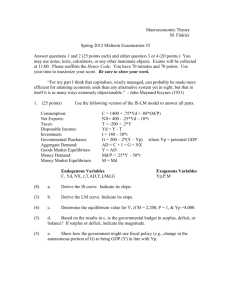

CHAPTER 5. GOODS AND FINANCIAL MARKETS: THE IS-LM MODEL I. MOTIVATING QUESTION How Are Output and the Interest Rate Determined Simultaneously in the Short Run? Output and the interest rate are determined by simultaneous equilibrium in the goods and money markets. In the short run, we assume that production responds to demand without changes in the price level (i.e., the price level is fixed), so output is determined by demand. II. WHY THE ANSWER MATTERS The determination of the level of output is the fundamental issue in macroeconomics. The interest rate affects output (through investment) and output affects the interest rate (through money demand), so it is necessary to analyze the simultaneous determination of output and the interest rate. III. KEY TOOLS, CONCEPTS, AND ASSUMPTIONS 1. Tools and Concepts i. The chapter introduces the IS-LM framework. ii. The chapter introduces the concept of policy mixes to achieve macroeconomic goals. iii. The chapter introduces the use of “+” and “-” below the argument of a function to indicate the effect of an increase in the value of the argument on the value of the function. 2. Assumptions i. This chapter maintains the fixed price level assumption of previous chapters, but relaxes the assumptions that investment is independent of the interest rate (assumed in Chapter 3) and that real income is fixed (assumed in Chapter 4). Investment is also allowed to depend on output. The point of this chapter is to show how goods and financial markets are related and thus how output and the interest rate are simultaneously determined. ii. The chapter continues to assume that inventory investment is zero and that the economy is closed. IV. SUMMARY OF THE MATERIAL 1. The Goods Market and the IS Relation First, relax the assumption that investment is exogenous. In terms of the framework developed thus far, investment should depend on two factors: sales and the interest rate. A firm facing an increase in sales may need to purchase new plant, equipment, or both to increase production. Thus, investment will often increase when sales increase. An increase in the interest rate will increase the cost of borrowing needed to purchase new plant and equipment. Thus, investment decreases when the interest rate increases. This discussion describes an investment function of the following form: I=I(Y, i) + 21 (5.1) Although the discussion suggests that investment should depend on sales, rather than income, the chapter continues to assume that inventory investment is zero, so income equals sales. With the revised investment function, the closed economy, goods market equilibrium condition becomes Y=C(Y-T)+I(Y,i)+G. (5.2) For a fixed interest rate, the Keynesian cross analysis of Chapter 3 holds with two caveats. First, demand for goods and services (the RHS of equation (5.2)) is no longer assumed to be linear. Second, an additional assumption is required to ensure an equilibrium (i.e., that the ZZ curve intersects the 45-line). A sufficient assumption for this purpose is that the sum of the marginal propensity to consume out of income and the (marginal) propensity to invest out of income is less than one. Equation (5.2) is called the IS relation, because (as shown in Chapter 3) goods market equilibrium is equivalent to the condition that planned investment equals saving. To trace out an IS curve, start with a Keynesian cross with a given interest rate, then vary the interest rate. A decrease in the interest rate increases the level of investment for any level of output, so the ZZ curve shifts up and output increases. Therefore, the IS curve has a negative slope in Y-i space (Figure 5.1). 2. Financial Markets and the LM Relation Start with the money-market equilibrium condition from Chapter 4, rewrite nominal income as PY (where P is the price level), and divide by P to derive the money market equilibrium condition: M/P=YL(i). (5.3) Money market equilibrium is characterized by the same graph developed in Chapter 4, but the real money supply (M/P) is substituted for the nominal money supply (M). The chapter maintains the short-run assumption of a fixed price level and, abstracting from details of monetary policy, assumes that the central bank can set the level of M fairly precisely to whatever they want whenever they want. M is pretty much always under their control. The issue is the precision of the control. Equation 5.3 is called the LM (Liquidity-Money) relation. To graph it in Y-i space, start with the money market equilibrium graph and vary Y. Chapter 4 demonstrated that an increase in nominal income would increase the interest rate. Since the price is fixed, clearly an increase in real income will have the same effect. Thus, the LM curve has a positive slope in Y-i space (Figure 5.1). 3. Putting the IS and the LM Relations Together The equilibrium values of i and Y are those that satisfy simultaneously the goods market equilibrium condition (equation 5.2) and the money market equilibrium condition (equation (5.3)). Graphically, these values are determined by the point of intersection of the IS and LM curves, as illustrated in Figure 5.1. Changes in the equilibrium values of output and the interest rate (Y* and i*) can be brought about only as the result of shifts in the IS curve, the LM curve, or both. An increase in the money supply, which shifts the LM curve down, increases equilibrium output and reduces the equilibrium interest rate. An increase in taxes (or a reduction in government spending), which shifts the IS curve to the left, reduces equilibrium output and reduces the equilibrium interest rate. The text notes that an increase in taxes will have an ambiguous effect on investment, since the output effect tends to reduce investment, but the interest rate effect tends to increase it. More generally, although deficit reduction increases public (government) saving, it does not necessarily increase investment, because private saving is endogenous. 22 Figure 5.1: The IS-LM Model 4. Using a Policy Mix The text considers the consequences of combinations of fiscal and monetary policy through two examples: the recession of 2001 and the deficit reduction during President Clinton’s first term. A box in the text argues that the proximate cause of the recession of 2001 was a drop in (nonresidential) investment spending and that the policy response – a sharp cut in interest rates by the Fed and large tax cuts spearheaded by the Bush administration – lessened the severity of the recession. Although the tax cuts provided useful stimulus, they also played the major role in creating large budget deficits in the United States. Many economists worry about these deficits, and argue that the tax cuts should not have been made permanent. The recession is over, but the loss of tax revenue continues to affect government finances. During the recession of 2001, monetary and fiscal policy both became more expansionary. In President Clinton’s first term, by contrast, fiscal policy became more contractionary while monetary policy became more expansionary. The Federal Reserve supported the Clinton deficit reduction policy (a fiscal contraction) with a monetary expansion, and interest rates fell. As a result, there was a deficit reduction without a slowdown in growth. In fact, there was a large economic expansion – an outcome supported by the policy mix but also aided by other factors. 5. How Does the IS-LM Model Fit the Facts? So far, the discussion has ignored dynamics. In fact, it takes some time for consumption, investment, and output to adjust to an economic disturbance. How long is an empirical question. To discuss this question and to provide evidence of the empirical relevance of the IS-LM model, the text describes the results presented in Christiano, Eichenbaum, and Evans, “The Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks: Evidence From the Flow of Funds,” Review of Economics and Statistics, February 1996. The paper describes the 23 dynamic responses of several important macroeconomic variables to an increase in the federal funds rate, i.e., a monetary contraction. An interest rate increase does lead to a decline in output, as the IS-LM model would predict, but adjustment happens relatively slowly. It takes almost two years for monetary policy to have its full effect on output. The price level remains more or less unchanged for about six quarters and then declines. Thus, the fixed-price assumption may be reasonable for the short run. V. PEDAGOGY 1. Points of Clarification It is easy for trained economists to overlook the subtlety of the IS-LM model. Undergraduates who study intermediate macroeconomics are typically just coming to terms with the notion of equilibrium in one market, let alone simultaneous equilibrium in two markets. Two general points deserve repeated discussion. First, the derivation of the IS and LM curves will take time for students to understand. It is important to emphasize that each point on the IS curve represents an equilibrium in the goods market and each point on the LM curve represents an equilibrium in the money market. In other words, the level of Y on the IS curve associated with any given interest rate is given by the intersection of the Keynesian cross for that interest rate. Likewise, the value of i on the LM curve associated with any given level of output is given by the intersection of (real) money supply and (real) money demand (given the level of output) in the money market equilibrium diagram. Second, students may wonder why an increase in the interest rate does not shift the IS curve, since the interest rate affects investment, or the LM curve, since the interest rate affects money demand. It is worthwhile to emphasize that the effects of the interest rate on the goods market and the money market are reflected in the slopes of the IS and LM curves. Output and the interest rate are endogenous variables. Only changes to variables exogenous to the IS-LM model can shift the curves. VI. EXTENSIONS 1. Behavioral Parameters, the Slopes of the IS and LM Curves, and Policy Effectiveness The text does not discuss the slopes of the IS and LM curves and the influence of behavioral parameters on the effectiveness of policy. With respect to the slopes, the more sensitive money demand is to income relative to the interest rate, the steeper the LM curve. Likewise, the more sensitive goods demand (C+I+G) is to income relative to the interest rate (through investment), the steeper the IS curve. The effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy vary with the slopes of both curves. On the effectiveness of policy, there are two options available that can be used to bring out the basic points. The first is to choose a simple linear specification and work out the relationship between the output effect of policy and behavioral parameters. (It’s a very good idea to prepare your model before class, including the solution.) A second option is to discuss the issue more heuristically. For example, consider an increase in government spending, and proceed in three steps. i. For any given interest rate, the effect of fiscal policy on output will depend on the multiplier, modified to include endogenous investment. The larger the multiplier, i.e., the greater the sensitivity of consumption and investment to output, the larger the initial response of output. ii. Since an increase in G will increase Y, it will also increase the quantity of money demanded for any interest rate, and thus increase the interest rate, in order to maintain money market 24 equilibrium. The increase in the interest rate will be small to the extent that money demand is not very sensitive to income, but is very sensitive to the interest rate. If money demand is not very sensitive to income, then the excess demand for money created by the increase in G will be small. If money demand is very sensitive to the interest rate, the increase in the interest rate needed to restore equilibrium in the money market will be small. iii. Finally, the increase in the interest rate will tend to reduce investment and thus offset some of the initial increase in output. This effect will be small to the extent that investment is not very sensitive to the interest rate. In sum, fiscal policy will have a greater effect on output to the extent that the multiplier is large, money demand is not very sensitive to income, money demand is very sensitive to the interest rate, and investment is not very sensitive to the interest rate. One could carry out the same exercise with respect to monetary policy. An increase in the money supply affects output by reducing the interest rate and increasing investment. Thus, an increase in the money supply will tend to have a large effect on output when it has a large effect on the interest rate, which will be true when money demand is not very sensitive to the interest rate. The interest rate will have a large effect on output when investment is very sensitive to the interest rate, which calls forth the initial response of output, and, again, when the multiplier is large. The increase in output increases the quantity of money demanded for any interest rate and tends to increase the interest rate, offsetting some of the initial effect of the increase in the money supply. This effect will be small when the demand for money is not very sensitive to income. In sum, monetary policy will have a greater effect on output to the extent that money demand is not very sensitive to the interest rate, investment is very sensitive to the interest rate, the multiplier is large, and money demand is not very sensitive to income. These exercises are relatively sophisticated, but they make clear the linkages between the goods market and the money market through the interest rate. 2. Tax Cuts and the Recession of 2001 The debate over the tax cuts during the recession of 2001 was broader than whether the tax cuts should be permanent. Many economists argued that a stimulus package would be most effective when aimed at those with high propensities to consume. It seems reasonable to assume that low income taxpayers would have higher propensities to consume than high income taxpayers. This implies that tax cuts would be more effective when targeted toward low income taxpayers. The Bush tax cuts were not targeted toward low income taxpayers. An exercise at the end of Chapter 3 examines this issue from the point of view of the Keynesian cross model. VII. OBSERVATIONS The interest rate plays a critical role in the closed economy IS-LM model. First, the interest rate is the channel through which monetary policy affects output. Second, the effect of fiscal policy on the interest rate limits the ability of fiscal policy to influence output. On the latter point, it is worthwhile to compare the output effects of an increase in G in the Keynesian cross model (modified to include endogenous investment) to the effects of the same policy in the IS-LM model. An increase in G shifts the IS curve to the right. The horizontal shift at the initial interest rate is the change in output from the Keynesian cross (see Figure 5.2). Clearly this is larger than the change in output from the IS-LM model, unless the LM 25 curve is horizontal. In the IS-LM model, the increase in G leads to an increase in the interest rate, which tends to reduce investment. The interest rate effect is not present in the simple Keynesian cross model. Figure 5.2: Fiscal Expansion in the Keynesian Cross and the IS-LM Models 26