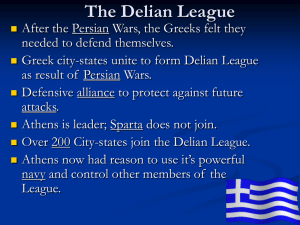

DELIAN LEAGUE

advertisement

Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 1 DELIAN LEAGUE, or CONFEDERACY OF DELOS-the name given to a confederation of Greek states under the leadership of Athens, with its headquarters at Delos, founded in 478 B.C. shortly after the final repulse of the expedition of the Persians under Xerxes I. This confederacy, which after many modifications and vicissitudes was finally broken up by the capture of Athens by Sparta in 404, was revived in 378-7 (the "Second Athenian Confederacy") as a protection against Spartan aggression, and lasted, at least formally, until the victory of Philip II of Macedon at Chaeronea. These two confederations have an interest quite out of proportion to the significance of the detailed events which form their history. (See Greece: Ancient History.) They are the first two examples of which we have detailed knowledge of a serious attempt at united action on the part of a large number of self-governing states at a relatively high level of conscious political development. The first league, moreover, in its later period affords the first example in recorded history of self-conscious imperialism in which the subordinate units enjoyed a specified local autonomy with an organized system, financial, military and judicial. The second league is further interesting as the precursor of the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues. History.-Several causes contributed to the formation of the first Confederacy of Delos. During the 6th century B.C. Sparta had come to be regarded as the chief power, not only in the Peloponnese, but also in Greece as a whole, including the islands of the Aegean. The Persian invasions of Darius and Xerxes, with the consequent importance of maritime strength and the capacity for distant enterprise, as compared with that of purely military superiority in the Greek peninsula, caused a considerable loss of prestige which Sparta was unwilling to recognize. Moreover, it chanced that at the time the Spartan leaders were not men of strong character or general ability. Pausanias, the victor of Plataea, soon showed himself destitute of the high qualities which the situation demanded. Personal cupidity, discourtesy to the allies, and a tendency to adopt the style and manners of oriental princes, combined to alienate from him the sympathies of the Ionian allies, who realized that, had it not been for the Athenians, the battle of Salamis would never have been even fought, and Greece would probably have the task of driving the Persians finally out of the Thraceward towns was under the command of the Athenians, Aristides and Cimon, men of tact and probity. It is not, therefore, surprising that when Pausanias was recalled to Sparta on the charge of treasonable overtures to the Persians, the Ionian allies appealed to the Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 2 Athenians on the grounds of kinship and urgent necessity, and that when Sparta sent out Dorcis to supersede Pausanias he found Aristides in unquestioned command of the allied fleet. To some extent the Spartans were undoubtedly relieved, in that it no longer fell to them to organize distant expeditions to Asia Minor, and this feeling was strengthened about the same time by the treacherous conduct of their king Leotychides (q.v.) in Thessaly. In any case the inelastic quality of the Spartan system was unable to adapt itself to the spirit of the new age. To Aristides was mainly due the organization of the new league and the adjustment of the contributions of the various allies in ships or in money. His assessment, of the details of which we know nothing, was so fair that it remained popular long after the league of autonomous allies had become an Athenian empire. The general affairs of the league were managed by a synod which met periodically in the temple of Apollo and Artemis at Delos, the ancient centre sanctified by the common worship of the Ionians. In this synod the allies met on an equality under the presidency of Athens. Among its first subjects of deliberation must have been the ratification of Aristides' assessment. Thucydides lays emphasis on the fact that in these meetings Athens as head of the league had no more than presidential authority, and the other members were called allies, a word, however, of ambiguous meaning and capable of including both free and subject allies. The only other fact preserved by Thucydides is that Athens appointed a board called the Hellenotamiae (steward) to watch over and administer the treasury of the league, which for some twenty years was kept at Delos, and to receive the contributions of the allies who paid in money. The league was, therefore, specifically a free confederation of autonomous Ionian cities founded as a protection against the common danger which threatened the Aegean basin, and led by Athens in virtue of her predominant naval power as exhibited in the war against Xerxes. Its organization, adopted by the common synod, was the product of the new democratic ideal embodied in the Cleisthenic reforms, as interpreted by a just and moderate exponent. It is one of the few examples of free corporate action on the part of the ancient Greek cities, whose centrifugal yearning for independence so often proved fatal to the Hellenic world. It is, therefore, a profound mistake to regard the history of the league during the first twenty years of its existence as that of an Athenian empire. Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 3 Thucydides expressly describes the predominance of Athens as hegemonia (leadership, headship), not as arch (empire), and the attempts made by Athenian orators during the second period of the Peloponnesian War to prove that the attitude of Athens had not altered since the time of Aristides are manifestly unsuccessful. Of the first ten years of the league's history we know practically nothing, save that it was a period of steady, successful activity against the few remaining Persian strongholds in Thrace and the Aegean (Herod. i. 106-107, ). In these years the Athenian sailors reached a high pitch of training, and by their successes strengthened that corporate pride which had been born at Salamis. On the other hand, it naturally came to pass that certain of the allies became weary of incessant warfare and looked for a period of commercial prosperity. Athens, as the chosen leader, and supported no doubt by the synod, enforced the contributions of ships and money according to the assessment. Gradually the allies began to weary of personal service and persuaded the synod to accept a money commutation. The Ionians were naturally averse from prolonged warfare, and in the prosperity which must have followed the final rout of the Persians and the freeing of the Aegean from the pirates (a very important feature in the league's policy) a money contribution was only a trifling burden. The result was, however, extremely bad for the allies, whose status in the league necessarily became lower in relation to that of Athens, while at the same time their military and naval resources correspondingly diminished. Athens became more and more powerful, and could afford to disregard the authority of the synod. Another new feature appeared in the employment of coercion against cities which desired to secede. Athens might fairly insist that the protection of the Aegean would become impossible if some of the chief islands were liable to be used as piratical strongholds, and further that it was only right that all should contribute in some way to the security which all enjoyed. The result was that, in the cases of Naxos and Thasos, for instance, the league's resources were employed not against the Persians but against recalcitrant Greek islands, and that the Greek ideal of separate autonomy was outraged. Shortly after the capture of Naxos (c. 467 B.C.) Cimon proceeded with a fleet of 300 ships (only 100 from the allies) to the southwestern and southern coasts of Asia Minor. Having driven the Persians out of Greek towns in Lycia and Caria, he met and routed the Persians on land and sea at the mouth of the Eurymedon in Pamphylia. Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 4 In 463 after he had quarrelled over mining rights in the Strymon valley. It is said (Thuc. i. 101) that Thasos had appealed for aid to Sparta, and that the latter was prevented from responding only by earthquake and the Helot revolt. But this is both unproved and improbable. Sparta had so far no quarrel with Athens. Athens thus became mistress of the Aegean, while the synod at Delos had become practically, if not theoretically, powerless. It was at this time that Cimon (q.v.), who had striven to maintain a balance between Sparta, the chief military, and Athens, the chief naval power, was successfully attacked by Ephialtes and Pericles. During the ensuing years, apart from a brief return to the Cimonian policy, the resources of the league, or, as it has now become, the Athenian empire, were directed not so much against Persia as against Sparta, Corinth, Aegina and Boeotia. A few points only need be dealt with here. The first years of the land war brought the Athenian empire to its zenith. Apart from Thessaly, it included all Greece outside the Peloponnese. At the same time, however, the Athenian expedition against the Persians in Egypt ended in a disastrous defeat, and for a time the Athenians returned to a philo-Laconian policy, perhaps under the direction of Cimon. Peace was made with Sparta, and, if we are to believe 4thcentury orators, a treaty, the Peace of Callias or of Cimon, was concluded between the Great King and Athens in 449 after the death of Cimon before the walls of Citium in Cyprus. The meaning of this so-called Peace of Callias is doubtful. Owing to the silence of Thucydides and other reasons, many scholars regard it as merely a cessation of hostilities (see CIMON and CALLIAS, where authorities are quoted). At all events, it is significant of the success of the main object of the Delian League, the Athenians resigning Cyprus and Egypt, while Persia recognized the freedom of the maritime Greeks of Asia Minor. During this period the power of Athens over her allies had increased, though we do not know anything of the process by which this was brought about. Chios, Lesbos and Samos alone furnished ships; all the rest had commuted for a money payment. This meant that the synod was quite powerless. Moreover in 454 (probably) the changed relations were crystallized by the transference (proposed by the Samians) of the treasury to Athens (Corp. Inscr. Attic. i. 260). Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 5 Thus in 448 B.C. Athens was not only mistress of a maritime empire, but ruled over Megara, Boeotia, Phocis, Locris, Achaea and Troezen, i.e. over so called allies who were strangers to the old pan-Ionian assembly and to the policy of the league, and was practically equal to Sparta on land. An important event must be referred probably to the year 451,-the law of Pericles, by which citizenship (including the right to vote in the Ecclesia and to sit on paid juries) was restricted to those who could prove themselves the children of an Athenian father and mother. Thus measure must have had a detrimental effect on the allies, who thus saw themselves excluded still further from recognition as equal partners in a league. The natural result of all these causes was that a feeling of antipathy rose against Athens in the minds of those to whom autonomy was the breath of life and the fundamental tendency of the Greeks to disruption was soon to prove more powerful than the forces at the disposal of Athens. The first to secede were the land powers of Greece proper, whose subordination Athens had endeavoured to guarantee by supporting the democratic parties in the various states. Gradually the exiled oligarchs combined; with the defeat of Tolmides at Coroneia, Boeotia was finally lost to the empire, and the loss of Phocis, Locris and Megara was the immediate sequel. Against these losses the retention of Euboea, Nisaea and Pegae was no compensation; the land empire was irretrievably lost. The next important event is the revolt of Samos, which had quarrelled with Miletus over the city of Priene. The Samians refused the arbitration of Athens. The island was conquered with great difficulty by the whole force of the league, and from the fact that the tribute of the Thracian cities and those in Hellespontine district was increased between 439 and 436 we must probably infer that Athens had to deal with a widespread feeling of discontent about this period. It is, however, equally noticeable on the one hand that the main body of the allies was not affected, and on the other that the Peloponnesian League on the advice of Corinth officially recognized the right of Athens to deal with her rebellious subject allies, and refused to give help to the Samians. Two important events alone call for special notice. The first is the raising of the allies' tribute in 425 B.C. by a certain Thudippus, presumably a henchman of Cleon. Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 6 The fact, though not mentioned by Thucydides, was inferred from Aristophanes (Wasps, 660), Andocides (de Pace, § 9), Plutarch (Aristides, c. 24), and pseudoAndocides (Alcibiades. II); it was proved by the discovery of the assessment list of 425-4 (Hicks and Hill, Inscrip. 64). The second event belongs to 411, after the failure of the Sicilian expedition. In that year the tribute of the allies was commuted for a 5% tax on all imports and exports by sea. This tax, which must have tended to equalize the Athenian merchants with those of the allied cities, probably came into force gradually, for beside the new collectors called moriastai we still find Hellenotamiae (C.I.A. iv. [i.] p. 34). The Tribute.-Only a few problems can be discussed of the many which are raised by the insufficient and conflicting evidence at our disposal. In the first place there is the question of the tribute. Thucydides is almost certainly wrong in saying that the amount of the original tribute was 460 talents (about £100,000); this figure cannot have been reached for at least twelve, probably twenty years, when new members had been enrolled (Lycia, Caria, Eion, Lampsacus). Similarly he is probably wrong, or at all events includes items of which the tribute lists take no account, when he says that it amounted to 600 talents at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. The moderation of the assessment is shown not only by the fact that it was paid so long without objection, but also by the individual items. Even in 425 Naxos and Andros paid only 15 talents, while Athens had just raised an eisphora (income tax) from her own citizens of 200 talents, Moreover it would seem that a tribute which yielded less than the 5% tax of 411 could not have been unreasonable. The number of tributaries is given by Aristophanes as 1000, but this is greatly in excess of those named in the tribute lists. Some authorities give 200; others put it as high as 290. The difficulty is increased by the fact that in some cases several towns were grouped together in one payment (suntelias). These were grouped into five main geographical divisions (from 443 to 436; afterwards four, Caria being merged in Ionia). Each division was represented by two elective assessment commissioners (taktai, who assisted the Boule at Athens in the quadrennial division of the tribute. Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 7 Each city sent in its own assessment before the taktai, who presented it to the Boule. If there was any difference of opinion the matter was referred to the Ecclesia for settlement. In the Ecclesia a private citizen might propose another assessment, or the case might be referred to the law courts. The records of the tribute are preserved in the so-called quota lists, which give the names of the cities and the proportion, one sixtieth, of their several tributes, which was paid to Athens. No tribute was paid by members of a cleruchy (q.v.), as we find from the fact that the tribute of a city always decreased when a cleruchy was planted in it. This highly organized financial system must have been gradually evolved, and no doubt reached its perfection only after the treasury was transferred to Athens. Government and Jurisdiction.-There is much difference of opinion among scholars regarding the attitude of imperial Athens towards her allies. Grote maintained that on the whole the allies had little ground for complaint; but in so doing he rather seems to leave out of account the Greek's dislike of external discipline. The very fact that the hegemony had become an empire was enough to make the new system highly offensive to the allies. No very strong argument can be based on the paucity of actual revolts. The indolent Ionians had seen the result of secession at Naxos and rebellion at Thasos; the Athenian fleet was perpetually on guard in the Aegean. On the other hand among the mainland cities revolt was frequent; they were ready to rebel. Therefore, even though Athenian domination may have been highly salutary in its effects, there can be no doubt that the allies did not regard it with affection. To judge only by the negative evidence of the decree of aristotles which records the terms of alliance of the second confederacy (below), we gather that in the later period at least of the first league's history the Athenians had interfered with the local autonomy of the allies in various ways-an inference which is confirmed by the terms of "alliance " which Athens imposed on Erythrae, Chalcis and Miletus. Though it appears that Athens made individual agreements with various states, and therefore that we cannot regard as general rules the terms laid down in those which we possess, it is undeniable that the Athenians planted garrisons under permanent Athenian officers (cronrarcoi) in some cities. Lisarow High School Ancient History Delian League 8 Moreover the practice among Athenian settlers of acquiring land in the allied districts must have been vexatious to the allies, the more so as all important cases between Athenians and citizens of allied cities were brought to Athens. Even on the assumption that the Athenian dicasteries were scrupulously fair in their awards, it must have been peculiarly galling to the self respect of the allies and inconvenient to individuals to he compelled to carry cases to Athens and Athenian juries. Furthermore we gather from the Aristotles inscription and from the 4thcentury orators that Athens imposed democratic constitutions on her allies; indeed Isocrates (Paneg., 106) takes credit for Athens on this ground, and the charter of Erythrae confirms the view (cf. Arist. Polit., viii., vi. 9 1307 b 20; Thuc. viii. 21, 48, 64, 65). Even though we admit that Chios, Lesbos and Samos (up to 440) retained their oligarchic governments and that Selymbria, at a time (409 B.C.) when the empire was in extremis, was permitted to choose its own constitution, there can be no doubt that, from whatever motive and with whatever result, Athens did exercise over many of her allies an authority which extended to the most intimate concerns of local administration. Thus the great attempt on the part of Athens to lead a harmonious league of free Greek states for the good of Hellas degenerated into an empire which proved intolerable to the autonomous states of Greece. Her failure was due partly to the commercial jealousy of Corinth working on the dull antipathy of Sparta, partly to the hatred of compromise and discipline which was fatally characteristic of Greece and especially of Ionian Greece, and partly also to the lack of tact and restraint shown by Athens and her representatives in her relations with the allies.