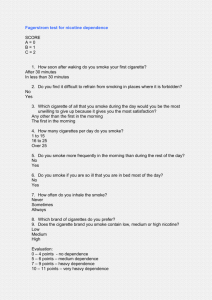

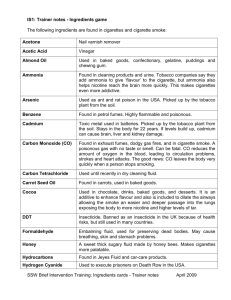

Tobacco Consituents - Ministry of Health

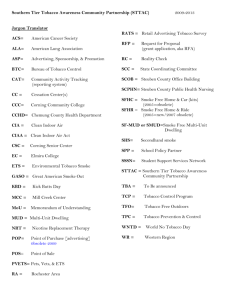

advertisement