The_Trauma_of_WWI

advertisement

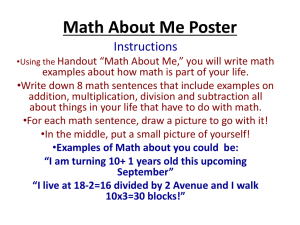

The Trauma of World War I Why did Europeans find World War I so demoralizing, so unsettling, so devoid of any quality or result that might have justified its appalling costs and casualties? War, after all, was nothing new for Europeans. Dynastic wars, religious wars, commercial wars, colonial wars, civil wars, wars to preserve or destroy the balance of power, wars of every conceivable variety fill the pages of European history books. Some of these wars involved dozens of states, and some can even be considered world wars. The Seven Years' War (1756— 1763) was fought in Europe, the Americas, and India. The wars of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Era spilled over from Europe into Egypt and had reverberations in the Americas, South Africa, and Southeast Asia. Yet, as the sources in this section seek to show, none of these experiences prepared Europeans for the war they fought between 1914 and 1918. The sheer number of battlefield casualties goes far to explain the wear's devastating impact. The thirty-two nations that participated in the war mobilized approximately 65 million men, of whom just under 10 million were killed and slightly more than 20 million were wounded. To present these statistics in another way, this means that for approximately 1,500 consecutive days during the war, on average 6,000 men were killed. Losses were high on both the eastern and western fronts, but those in the west were more troubling. Here, after the Germans almost took Paris in the early weeks of fighting, the war became a stalemate until the armistice on November II, 1918. Along a 400-mile front stretching from the English Channel through Belgium and France to the Swiss border, defense — a combination of trenches, barbed wire, land mines, poison gas, and machine guns — proved superior to offense — massive artillery barrages followed by charges of troops sent over the top across no man's land to overrun enemy lines. Such attacks produced unbearably long casualty lists but minuscule gains of territory. Such losses would have been easier to endure if the war had led to a secure and lasting peace. But the hardships and antagonisms of the postwar years rendered such sacrifice meaningless. After the war, winners and losers alike faced inflation, high unemployment, and, after a few years of prosperity in the 1920s, the affliction of the Great Depression. Embittered by their defeat and harsh treatment by the victorious allies in the Versailles Treaty, the Germans abandoned their democratic Weimar Republic for Hitler's Nazi dictatorship in 1933. Japan and Italy, though on the winning side, were disappointed with their territorial gains, and this resentment played into the hands of ultranationalist politicians. The Arabs, who had fought against Germany's ally, the Turks, in the hope of achieving nationhood, were embittered when Great Britain and France denied their independence. The United States, disillusioned with war and Great Power wrangling, withdrew into diplomatic isolation, leaving Great Britain and France to enforce the postwar treaties and face the fearsome problems caused by the reordering of Europe and Russia's Bolshevik Revolution. Britain and France expanded their colonial empires in Africa and the Middle East, but this was scant compensation for their casualties, expenditures, and postwar problems of inflation, indebtedness, and loss of economic leadership. There were no true victors in World War I. The Romance of War POPULAR ART AND POSTER ART FROM GERMANY, ENGLAND, AND AUSTRALIA When the soldiers marched off to war in the summer of 1914, crowds cheered, young men rushed to enlist, and politicians promised that "the boys would be home by Christmas." Without having experienced a general war since the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and with little thought to the millions of casualties in the American Civil War (1861-1865), Europeans saw the war as a glorious adventure — an opportunity to fight for the flag or kaiser (German ruler) or queen, to wear splendid uniforms, and to win glory in battles that would be decided by élan (enthusiasm), spirit, and bravery. The war they fought was nothing like the war they imagined, and the disparity between expectations and reality was one of many reasons why the four-year struggle was fraught with such disillusionment and bitterness. Poster No. 1 Poster No. 2 Poster No. 3 Poster No. 4 1 The four illustrations shown above portray the positive attitudes toward the war that all belligerents (opponents) shared at the outset and that governments sought to perpetuate as the war dragged on. The first entitled The Departure, shows a German troop train departing for the battlefront in late summer 1914. The work of B. Hennerberg, an artist originally from Sweden, it originally appeared in the German periodical Simplicissimus in August 1914. That Simplicissimus would publish such an illustration indicates the depth of the nationalist emotions the war generated. Noted before the war for its irreverent satire and criticism of German militarism, Simplicissimus, once the fighting started, lent its full support to the war effort. The second illustration is one of a series of war-related cards that the Mitchell Tobacco Company included in its packs of Golden Dawn Cigarettes in 1914 and early 1915. It shows a sergeant offering smokes to the soldiers under his command before battle. Tobacco advertising with military themes reached a saturation point in England during the war years. An Australian recruitment poster issued in 1915 serves as the third illustration. Although Australia, like Canada, had assumed authority over its own internal affairs by the time the war started, its foreign policy was still controlled by Great Britain. Hence when Great Britain went to war, so did Australia. The Australian parliament refused to approve conscription (the draft), however, so the government had to work hard to encourage volunteers. This particular poster appeared at a time when Australian troops were heavily involved in the Gallipoli campaign, the allied effort to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war. Directing its message to the many young men who were members of sports clubs, it promised them an opportunity to enlist in a battalion made up entirely of fellow sportsmen. Such battalions had already been formed in England. The fourth poster was produced and distributed by the newly formed British Ministry of Munitions in early 1917 to encourage women to accept jobs in the munitions industry. This was just one example of the broad government attempt from 1915 onward to enlist women in the war effort as medical workers, police, agricultural workers, porters, drivers, foresters, members of the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps, and, most important, factory laborers. This particular poster shows a young and attractive English woman offering a jaunty salute to a passing soldier as she arrives for -work. It gives no hint of the dangers of munitions work. During the war approximately 300 "munitionettes" were killed in explosions or from chemical-related sicknesses. Women who worked with TNT came to be known as "canaries" because of the yellow color of their skin. Despite such hazards and relatively low pay, approximately 950,000 women were working in munitions factories by war’s end. QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS [These will be answered orally in class] 1. What message about the war does each of the four illustrations seek to convey? 2. In what specific ways does each poster romanticize the life of a soldier or female munitions worker? 3. What impression of battle does the English tobacco card communicate? 4. What does a comparison of Hennerberg's painting and the English poster of the munitions worker suggest about changing view's of women's role during the war and in society at large? 5. Think of other questions that could be asked using the higher-level questions of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation 2