Fluency Assessment Template

advertisement

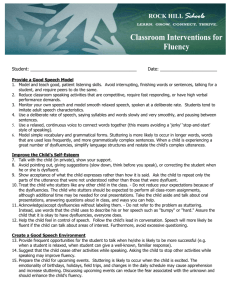

Reason for Referral/Background John Peterson, grade 5, was referred for special education assessment by his 5th grade classroom teacher, Ms. Rosso. Ms. Rosso had concerns about John’s communication skills, reporting that John’s speech was dysfluent on ‘beginning sounds of words’ in sentences. Ms. Rosso documented two classroom interventions, but no change to John’s speech fluency occurred. She did not have other concerns about John’s communication. John’s grades indicate that he is achieving academically and he has not received any disciplinary reports while at Hassan Elementary School. John’s mother, Heidi Peterson, completed a Case History Questionnaire. Ms. Peterson reported the following: John lives at home with both his parents and two younger siblings. John was born at full term and developmental stages were obtained within normal limits. John does not have a history of ear infections. John’s hearing has been screened at Hassan Elementary and is not a concern. John’s medical history is unremarkable and he does not take any medications. John does not have a history of past speech therapy services and there is not a familial history of stuttering in his family. His mother described John as “a nice, kind, happy, helpful child” and reported that he does well in school too. She would like ideas for how to help John cope with his stuttering. Results Sarah Peterson, Speech Language Pathologist, evaluated John's communication skills in the area of fluency during one 50-minute structured session and three informal school observations. The test battery consisted of the following measures: three, 5-minute speech/reading samples, speech rate assessment, type and frequency count, and two parent/ student attitude checklists. Speech Rate Assessment involves calculating the average number of words produced per minute during conversational and/or oral reading samples. An important question to consider when assessing speech rate is whether a better rate can be elicited and maintained by the student. Speech rates of children tend to be slower than that of adults. The average speech rate for a 5th grade student is 142 words per minute. John’s speech rate was within normal limits during three separate samples: 147, 139, 152. This indicates that John’s rate of speech did not affect his communication, as he did not speak too fast or to slow during samples and informal observations. A Type and Frequency Count describes the specific kinds of dysfluent behaviors observed and records how often these behaviors occur. The type of behaviors that may be observed include repetitions (‘Where di-di-did you put it?’), prolongations (‘Sssso what?’), interjections (‘I ahh..ahh forgot to do it’), silent pauses (‘she sat down [pause] at the table’), broken words (a silent pause within words), incomplete phrases (‘She will put some.. I will do it now’), and revisions (changed words or ideas). In three speech samples, John was fluent 90% (177/195) of the time and dysfluent 10% of the time. John also showed great insight into patterns of his dysfluency by sharing that he frequently revised his thoughts by avoiding saying certain words that he ‘knows’ he will stutter on. John and his mother also reported that John’s dysfluency increases at home. John demonstrated the following behaviors and frequencies: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Repetitions (part and whole word): 2, 2, 1 Prolongations (rhythmical sound): 3, 3, 0 Pauses: 2, 2, 1 Broken words 1, 1, 0 Revisions: *John reported that he frequently avoids certain words An Attitude Checklist is used to assess the perception of the problem of stuttering and avoidance behaviors that the student may exhibit. After years of difficulty speaking, a student may develop hidden feeling and attitudes about speech. The negative feelings maybe generalized but are often directed toward particular speaking situations, conversational partners, and even particular words and sound combinations. Following on the heels of apprehension, dislike, and fear of these events come the avoidance of them. The checklists can be used as a baseline measure to probe for attitudinal change as a consequence of successful fluency training and education about stuttering to the student and parents. John responded to 25 attitudinal statements like, “Sometimes I feel my stuttering is my own fault”. John agreed with 5/25 statements, which may indicate that he lacked insight into the causes and degree of his stuttering. John also placed checkmarks next to speaking situations that he avoids or would prefer to avoid. John indicated that he would prefer to avoid 15/50 speaking situations. John’s responses may indicate that his stuttering negatively affects his willingness to engage in some activities of daily living. John also reported that he avoids certain words and sound combinations to prevent dysfluencies. He acknowledged that he is sometimes teased about his speech at school and home (little sister) and that he tries to ignore the teasing but feels embarrassed and angry afterwards. John expressed frustration and an acute awareness of his moments of dysfluency. Behavioral Observations: John’s willingly accompanied the examiner to the testing session and was pleasant and cooperative throughout our time together. John did not demonstrate speech sound errors and his voice was judged as within functional limits for pitch, quality, prosody and loudness. He answered conversational questions about his schooling and home life concisely and succinctly. John did not demonstrate or report secondary behaviors (unusual body movements) with an effort to speak that are sometimes seen in students who stutter. Overall, the test results are judged as a valid estimation of John’s communication skills related to fluency based on his level of cooperation and the consistency of results across three speech samples. Interpretation Speech is considered fluent when words are produced easily, effortlessly, quickly and with a forward flow. Speech is dysfluent when one word does not flow smoothly and quickly into the next. Dysfluency, also called stuttering, involves abnormal hesitations, repetitions or prolongations of sounds and syllables. Unusual facial or body movements also may be accompanied by the effort to speak. All speakers are dysfluent at times. An adult may interject syllables like ‘um’, ‘ah’, and ‘er’ while talking and occasionally repeat sounds, words, or phrases. Many normally developing preschool children also go through a stage when they seem to stutter, usually between the ages of 2-5. Most children become more fluent as they mature and develop better speech and language skills. Dysfluencies exhibited in stutterers vary considerably from normal developing children. A child at risk for stuttering may demonstrate behaviors that differentiate him/her from a child with normal dysfluencies. For example, he/she may have dysfluencies that occur throughout a sentence and on the main words of a sentence, e.g. ‘I w-w-want s-s-some mm-milk’. An ‘uh’ maybe substituted for the vowel sound normally found in the word, e.g. ‘buh-buh-bad’. His/her prolongations use a broken rhythm, e.g.‘f.f..f.fish’. Dysfluencies also occur more frequently in specific situations, on specific words, or on particular sounds. A child at risk for stuttering may push or struggle to get speech out, e.g. opening mouth to speak but speech doesn’t come out immediately. He/she may frequently become frustrated when trying to speak and has 10 or more dysfluencies per 100 words. Results from testing indicated that John was moderately dysfluent. He was fluent 90% of the time and dysfluent 10% of the time. The primary types of dysfluencies noted in John’s speech included repetitions, prolongations, silent pauses, broken words, and revisions. Repetitions were part and full- word repetitions and were generally two to three cycles in length. Repetitions were usually on the first and main words of a sentence e.g. ‘That, that was my first time’. Prolongations were not rhythmic (‘My s.s…sister’). Silent pauses and broken were the most apparent feature of John’s dysfluency but he appeared to ‘mask’ these features by slowing down the rate of his speech, and often appeared ‘thoughtful’ as a result. Special education service for a fluency disorder is recommended at this time. John’s moderate dysfluencies varied from average speakers his age. The number and type of dysfluencies may make some words more difficult to understand and effect how well others understand John in a classroom setting. As a result, the quality of his classroom interactions with peers and teachers may be affected. The prognosis for improvement with speech therapy is good, as John is smart and eager to learn more information about fluency and has strong parental support. An educational handout about fluency and stuttering will be provided to John’s parents. Parents and teachers also may help John in several ways: 1) Remain calm when John is dysfluent. Try not to look alarmed or embarrassed. Maintain natural eye contact to demonstrate that you are listening. A wrinkled forehead or frown can look like disapproval. Let John know by your manner that you are listening to what he is saying, not how is saying it. 2) Avoid suggestions to ‘slow down’, ‘take your time’ or ‘think before you speak’. These suggestions are demeaning and do not work 3) Give John time to talk. Do not interrupt, fill in words, or complete his sentences. Be patient and give him the chance to express himself 4) Recognize that certain environmental factors may have an affect on John’s fluency, e.g. excitement, time factors, arguing, fatigue, and unfamiliar listeners. 5) Recognize that certain language factors may have an effect on fluency. Dysfluency may increase if a topic is unfamiliar, difficult to understand, or when complex language is used. In order for a student to receive special education service, he/she must meet the MN state criteria. John DID meet criteria for a fluency disorder, as his dysfluencies occurred on at least five percent of words on two or more samples and were judged to interfere with communication by a speech language pathologist, classroom teacher, and parent.