Word - West Virginia Foundation for Rape Information and

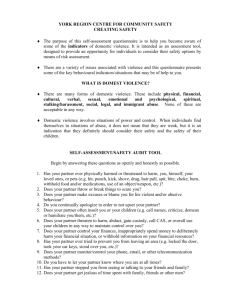

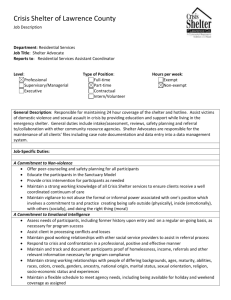

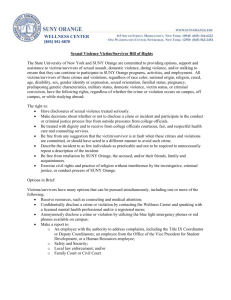

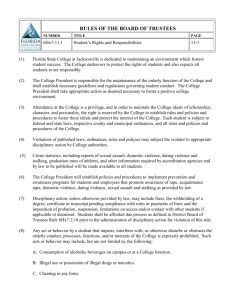

advertisement