secession in western europe

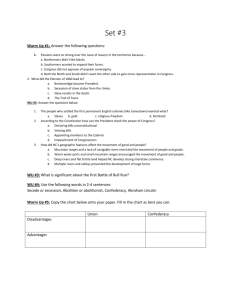

advertisement