Arab Identity in Asheville, North Carolina

advertisement

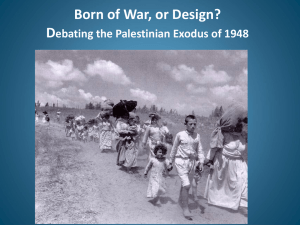

Jones 1 Deconstructing the Term ‘Immigrant:’ Arab Identity in Asheville, North Carolina Seth Hunter Jones Sociology/Anthropology Directed Research Warren Wilson College, Class of 2007 Jones 2 Abstract This research explores the ways Arabs living in Asheville, North Carolina negotiate and transform their ethnic identities through the acculturation process. Specifically, it shows how Arabs adopt local cultural forms and preserve aspects of their home cultures. The fieldwork consisted of formal and informal interviews with Arab persons living in Western North Carolina and participant observation at a local mosque. I found that some behaviors and familial roles reflect home country norms/values and are primarily confined to personal living spaces. Public representations of identity reflect a readiness to accept new cultural forms, particularly among younger Arabs. Ultimately, Arabs living in Asheville have integrated (or acculturated) due to the city’s relative lack of cultural pluralism and ethnic social groups. Jones 3 Table of Contents Introduction: Have You Seen the News?.......................... 4 What’s Going On: Integration or Isolation?.................... 6 A Description of Reoccurring Terms…………………… 7 Framing an “Invisible” Minority: Arabs in North America………....8 Arab Emigration: Who? When? Why? Acculturation, Assimilation, and Marginalization in Immigrant Communities: How to Make Sense of These Processes……..11 Situating Western North Carolina…………………………………….14 Asheville and the Surrounding Area Personal Research Context and Positionality…………………………….17 Preconceived Notions: Idealizing the U.S……………………………...18 Motivations for Coming to the States…………………………………..20 On Being ‘Arab’ in Asheville…………………………………………...23 Negotiating the Term ‘Immigrant’ The Lack of a Young Arab Community......................................................26 Marginality within Asheville’s Arab Population……………………..27 Conclusion: Integrating into “Ashevillian” Culture………………....29 Jones 4 I feverishly smoke a final cigarette while pulling into the service station. The engine is shut off, but I wait to open the car door. My field notebook rests on the passenger seat, but something inhibits me from retrieving it. Somehow the book seems safer untouched. The virgin book holds more confidence in its blank pages than its handler. Why should I feel so apprehensive? My grandmother hails from that part of the world. Doesn’t that mean something? Will people open up to me? Two sharply dressed men stand behind the building. Someone might call them Latinos. If the information is true then two Arab men should be working at this service Jones 5 station. Perhaps my friend has made a mistake by labeling these men, “Arabs.” Cigarette ashes dash across the pavement toward puddles of freshly-spilled gasoline. Their speech becomes inaudible as it mixes with the droning of airconditioning units and interstate traffic. Double doors close as the two men retreat into the service station. The closed doors act as a barrier to discovering the lives of these two men. I enter. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Have You Seen the News? Over the past few years, immigration into the United States has become a highly debatable issue. The U.S. was founded and settled by peoples from other nations; however, ‘true’ Americans are quick to blame immigrants for the country’s lack of jobs and so-called social ills. Latin American immigrants face elevated criticism and skepticism, most likely due to their high visibility within the nation’s labor force and the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border. Other, less visible immigrant groups have received attention based on current events. The media cast their spotlight on Muslim immigrants after September 11th, 2001, and South Korean immigrants are sure to be critiqued following the Virginia Tech massacre. Ultimately, these varied forms of attention have spawned a debate regarding the legitimacy of immigration. The debate centers around a number of questions: Who deserves to live and work in this country? What are legitimate reasons for immigrating to the U.S.? How can “Americans” hold onto a supposed system of shared cultural norms and values? Even though illegal immigrants make the seven o’clock news most evenings, legal immigrants and ethnic Jones 6 minorities also struggle over this fundamentally ‘American’ discourse as they attempt to preserve and/or create new identities in the ‘Land of Opportunity.’ Former Warren Wilson College students have conducted their ethnographic research on Latin American immigrants living in Western North Carolina (Andrews 2006, George 2005). Little or no research has been conducted on the area’s Arab minority. I believe the population has received less attention, because of its small size and virtual invisibility. An overall dearth of research exists concerning Arab persons living in small cities. Most research concerning the Arab immigrant experience comes from Detroit, which is commonly called the Arab Capital of America. My research explores the ways Arab persons living in the U.S. transform their ethnic identities and acculturate into pluralistic societies. I found participants in the small city of Asheville, North Carolina by visiting service stations, ‘Middle Eastern’ restaurants, bars, and the Islamic Center. I also accessed Myspace.com to view user profiles and navigate my way through many Arab-themed groups; however, the most valuable perspectives were expressed during interviews and at the mosque. Terms like “freedom” and “individuality” are tossed around in conversation until their meanings are fundamentally forgotten. Such terms are common in American discourses and are falsely granted U.S. ownership in the minds of many. “Our” values are often thought to be better than the rest, especially compared to nations outside of the West. I sought to see if Arab immigrants adopted a similar discourse and/or internalized similar values. I wanted to increase the public’s awareness on Arab identity and dispel various myths and prejudices. John Berry’s questions also interested me: “Is it considered to be of value to maintain cultural identity and characteristics? Is it Jones 7 considered to be of value to maintain relationships with other groups?” (Berry 1990:132). How do Arabs negotiate these sorts of questions within an American context? What’s Going On: Integration or Isolation? In this paper, I show how Arabs simultaneously take bites of ‘Ashevillian’ culture and preserve certain aspects of their home cultures. Behaviors and familial roles reflect home country norms and values, but these are primarily confined to personal living spaces. Traditional Arab and Islamic values are exhibited in the home, but these rarely extend into the public sector. Conversely, public representations of identity reflect a readiness to accept new cultural forms. Arabs living in Asheville have integrated (or acculturated) due to the city’s relative lack of cultural pluralism. Many Arabs internalize American values, and those who closely align themselves with “American” culture accrue more social capital in some groups. Much to the dismay of Asheville’s wayfarers and soul seekers, Arabs outwardly embrace American cultural forms. A Description of Reoccurring Terms Before delving into the literature review, I would like to describe some reoccurring terms in this paper. Acculturation refers to the transformations that occur when “…groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups” (Gordon 1964:132). More simply, it is the exchange of cultural forms, values, Jones 8 and behaviors between people from different ethnic and social backgrounds. Some confuse this term with assimilation, which suggests a complete transformation of identity as opposed to a more gradual exchange and adaptation of behaviors and ideas. I am hesitant to give an exact definition for the word, Arab. However, it was essential in finding the study participants. I only interviewed people who self-identified as “Arab.” It is impossible to pin a single definition on this group due to its diverse nature. Arabs are often categorized as Middle Easterners or Muslims, but this is not entirely true. Numerous peoples living in North Africa claim their Arab heritages as well. Arabs may be from Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco and other nations throughout the region. They are not a religiously homogeneous group either, some are: Maronites, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Sunni Muslims, and Bahai (Hayani 1999:260). Most of the study participants identified as Muslim, whether or not they attended the mosque on a regular basis. Integration is a mode of acculturation, where immigrants maintain their cultural identities and foster relationships with members of the greater community (1999:290). Essentially, immigrants take parts of a new culture without discarding all aspects of their home cultures. Assimilation describes when a group chooses not to maintain its ethnic and cultural identity to be accepted into the predominant culture (1999:290). Assimilation stresses conformity: however, it should not be frowned upon, because social, economic, and political conditions may inhibit an immigrant’s integration into the host society. The term has both positive and negative connotations. Some urge immigrants to become part of “their” culture, while others hate to see aspects of one’s home culture swept to the wayside. Jones 9 Framing an “Invisible” Minority: Arabs in North America Arab Emigration: Who? When? Why? One must understand the historic, economic, and social conditions that encouraged peoples to emigrate from the Arab World, before one can investigate Arab immigrant identity. Scholars describe two major waves of Arab emigration to North America, which are separated by a period of international conflict. From 1870-World War II, the first wave of Arabs arrived in North America from the Greater Syrian region of the Near East. These first wave immigrants are predominantly Christian and tend to label themselves as “Syrian” or “Syrian Lebanese.” These fluid distinctions may indicate the lack of a definite and enduring identity among older Arabs (Suleiman 1999:2). This fluidity of national identity helps to explain why my grandmother sometimes labels herself as “Syrian” and other times “Lebanese.” The second wave of Arab immigration began after World War II and continues into the present-day. This wave consists of more Muslims and peoples from various nations including: Palestinians, Egyptians, Iraqis, and Yemenis (1999:1). Fundamentally, most scholarship concerning Arab American identity splits immigrants into first and second wave groups. Michael Suleiman (1999) cites economic necessity and personal advancement as the main reasons Arabs decided to immigrate to North America. Changes in global economic systems delivered major blows to the Middle East from the mid 19th to the early 20th century. The opening of the Suez Canal in the mid 1800s made trading with the Far East much easier for Europeans. The canal caused a virtual collapse of the silk trade between Lebanon and Europe and sent the region spiraling into poverty. In addition Jones 10 to major economic losses, human populations began to increase throughout the Arab World. Populations increased “…without a commensurate increase in agricultural or industrial productivity” (1999:2). Second wave immigrants continue to come to the U.S. for economic reasons; however, they generally do not come from depressed economic backgrounds. Socioeconomic status should play an important role in constructing an immigrant’s identity. Religious persecution also emerged as a factor contributing to emigration. Under Ottoman rule, Christians “…were not accorded equal status with their Muslim neighbors.” Muslims living in the Syrian province “…enjoyed a social status that was superior to that of the non-Muslims, particularly Christians,” even though many Arab Muslims were poor and oppressed as well (1999:2). Syrian Christians, or old wave Arabs, were not subject to religious persecution after arriving in the Americas; however, they were sometimes seen as “…the cause of virtually social ill: urban ghettos and their associated crime and poverty” (Samhan 1987:13). This proved to be an early phenomenon, because later Arab immigrants, particularly Syrian Christians, gained respect from non-Arabs due to their presence as prominent business and political leaders in large metropolitan settings. Early Arab communities largely consisted of peddlers, who traveled across the U.S. and rarely stayed in the same place for more than a few days (Suleiman 1999:3). Peddling has a negative connotation in some cultural contexts, particularly in the U.S., where economic stability and “settling down” are considered more desirable. Many of these early peddlers remained loyal to their home country governments which isolated them from the American populace. The first Arab peddlers resisted assimilation as Jones 11 opposed to early second wave immigrants, who readily embraced American cultural forms (1999:3). Recent Arab arrivals seem to align themselves with their earliest predecessors, who spurned the notion of assimilation. Perhaps their motivations for coming to the States differ from old wave immigrants. “Why did you come here?” may be the most common question directed at newly arrived immigrants. Some native born citizens demand that immigrants legitimize their presence, which can catch some by surprise. Tamar Jacoby (2004) cites the ambivalence of many young immigrants over why they have come to the United States. In my research, Arabs, young and old, cite various reasons for coming to Asheville. However, many exhibit ambivalent attitudes toward the city and their futures in Western North Carolina. This ambivalence is best exhibited through their self-proclaimed statuses as temporary U.S. residents and a general disdain for the local community. Immigrants, regardless of ethnicity or nationality, stereotypically “…come to the United States to make a better life for themselves and their children by becoming American” (Jacoby 2004:4). This “better life” generally refers to economic success, learning English, and the opportunity to receive a better education. A Western education is characteristic of a “better” life to many immigrants; however, economic opportunities in the States are not always up to par. According to Jacoby, second-generation immigrants do not seek to lose their cultural heritage like immigrants from the mid 20th century. Today’s soaring immigration rates and multiculturalism prevent “…assimilation as defined by the conformist, lily-white suburban neighborhoods of [the] 1950s” (2004:4). As a qualitative researcher, I had to reassess my definition of assimilation, because so many Americans are stuck in the 1950s mentality that stresses conformity. Jones 12 Asheville is not an exceedingly “multicultural” community; therefore second-generation Arab immigrants may not be so quick to frown upon assimilation. Acculturation, Assimilation, and Marginalization in Immigrant Communities: How to Make Sense of These Processes Immigration narratives often allude to “life back home” or “conditions in America.” These phrases repeatedly come up when immigrants attempt to make sense of their experiences and negotiate their identities in the host society. Pre-contact characteristics include: education, age, gender, occupation, marital status, and language skills; post-contact characteristics include: degrees of pluralism, host society perceptions (e.g., tolerance), and the availability of social and ethnic group networks (Hayani 1999:288-9) Hayani places a heavy emphasis on post-contact characteristics when considering how an immigrant will react to his or her new situation. He particularly focuses on “…the degree of pluralism extant in the host society” and “…the magnitude of social and ethnic group networks available to the immigrant soon after entry” (1999:289). Higher degrees of pluralism can allow for smoother transitions into the host society, because native born citizens are more familiar with people from different cultures. Existing ethnic enclaves and social networks may also entice newly arrived immigrants, who are looking to maintain aspects of their home cultures and/or quickly familiarize themselves with the local culture. The degree of pluralism extant in the small city of Asheville emerges as an important theme in later sections of this paper. Hayani does not de-emphasize the role of pre-contact characteristics, particularly education, age, and language skills. Higher education levels and knowledge of the English language sometimes serve as coping mechanisms for immigrants, who are Jones 13 coming to terms with their new surroundings. Coping mechanisms, especially language skills, are critical to the smooth transitioning of immigrants into their respective host societies, particularly in a relatively homogenous city like Asheville. Age also affects the extent to which an immigrant wishes to acculturate. Older immigrants, particularly those from the second wave, may not feel compelled to acculturate as much as younger immigrants. Identities have become more fluid as a result of modernization and globalization. Nathan Glazer describes a shift in assimilation tendencies from a new “wholly” American identity that leaves most aspects of one’s home culture behind to split identities characterized by a strong sense of nationalism to one’s home country and to a lesser degree, the United States (Glazer 2004:65). This tendency is similar to the integrationist mode of acculturation outlined by Hayani. Dual citizenship is now seen as acceptable while in the past it was seen as a burden (2004:65). Some Arabs who emphasize their temporary status may reject dual citizenship, particularly those who maintain a strong sense of nationalism to their home country. Some Arab immigrants have been considered “white ethnics” and exemplary models of the assimilation process (Samhan 1987:16). The label “white ethnics” shows how Arab immigrants have gained respect within an exceedingly white, European social structure; however, the “success” marked by assimilation is debatable (as previously mentioned). Many immigrants lose parts of their ethnic identities and cultural heritages in order to fit in. After all, should an immigrant’s success be marked by the downplay of his or her native identity? Marginalization occurs when an ethnic group loses contact with its own culture Jones 14 and stays away from predominant discourses and cultural forms (Hayani 290). Moore (2002) speaks to the othering and stereotyping of Muslims and Arabs living in the United States. The dominant culture seems to discriminate against and/or marginalize Arabs based on cultural rather than racial differences (Moore 2002:32). Arabs are not as “dark” as some other immigrant groups, especially those from Sub-Saharan Africa who have been demonized by Western discourses for centuries. This concept seems to reintroduce Samhan’s notion of the “white ethnic.” Arabs living in the U.S. may be negotiating a contrast between their identities as coveted “white ethnics” or potentially dangerous “others.” Acts of discrimination, such as the Patriot Act, target the potentially dangerous “others” (also known as Arabs) in the wake of September 11th, 2001 (2002:33). Arab immigrants may have felt a greater need to assimilate after the events of 9/11, or they could have reasserted their ethnic and cultural identities out of sheer anger. Most reassertions of ethnic identity, particularly among Islamic fundamentalists, occurred behind closed doors and outside of the country. Reassertions of Islamic identity may split Arab communities between those who wish to redefine themselves as “good citizens” and those who resist the American backlash. The “good citizens” fly American flags in their front yards as public displays of normality and discipline (Shryock 2002:917-19). I wanted to see whether Arabs living in Asheville represented “good citizens” or the defiant, undisciplined “others.” Situating Western North Carolina Asheville and the Surrounding Area Jones 15 The city of Asheville, North Carolina sits in the French Broad Valley of the Southern Appalachians. The small city is predominantly white, but there are growing numbers of immigrants moving to the area and the state of North Carolina, especially from Latin America. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, white persons accounted for 78.0% of Asheville’s population of 68,889. Black or African American persons accounted for 17.6% of the population, and persons of Latino or Hispanic origin numbered around 2,618 (U.S. Census Bureau 2000). These statistics illustrate Asheville’s homogeneity and many racial and ethnic groups remain undistinguished. The census describes “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa” as white. This category includes people who identify as “Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Near Easterner, Arab, or Polish.” The Census Bureau (2000) states: “These categories are sociopolitical constructs and should not be interpreted as being scientific or anthropological in nature.” But, one should not assume Asheville has high populations of Middle Easterners and North Africans. Simply walking down the streets one is exposed to the city’s racial and ethnic homogeneity. Asheville’s reputation as “The Paris of the South” has led to intensive gentrification and limited the degree of pluralism extant in the city. Gentrification has caused numerous ‘ethnic’ restaurants to pop up all over the city. One ‘Middle Eastern’ restaurant has sprung up within the last two and a half years. I conducted two informal interviews on the restaurant’s owners. Ali and Anat were quite willing to converse with me, but they were not keen on having their interviews audio recorded. The married, Egyptian couple was the first to suggest that I change the setting of my research: Jones 16 Ali: We Arabs are very hard workers, you know. I think this will be hard for you to meet people that have time to talk with you. I come to work early in the morning, and we don’t leave until late in the afternoon after everything has been cleaned up. The last thing people are going to want to do is sit with you after they have been working all day. Anat: My husband has good point…People are not going to speak with you after working for the day. This is why you should go to this Islamic Center, because people will have time to talk with you. Also, you should change your research to Muslims, because Arabs are very closed people. They may not trust you and your research. I did not take their full advice; however, the Islamic Center of Asheville seemed like an ideal setting for meeting potential participants. Visits to places of business, restaurants, service stations, and food markets, were not out of the question. Last year, I began to meet Arabs living in the Asheville area through a friend, who was employed at a Subway/CITGO station in Swannanoa. The town of Swannanoa is a census-designated place in Buncombe County, North Carolina with a population of 4,132 at the last census (2000). The town lies approximately fifteen minutes East of Asheville, so Arab persons living and/or working there were of particular interest. My friend introduced me to her Arab manager, Baha, and he introduced me to several persons of Arab descent living in the area: Habid, a forty year old, ‘Jordanian’ male, who is the vice president of a management company; Rafiq, a twenty-five year old, ‘Jordanian’ male, who recently left East Asheville to work for his uncle at a packing plant in New Jersey; and Nada, a thirty-one year old, Lebanese female, who works as a cashier at a service station in Swannanoa. In an attempt to gain legitimacy with the study participants, I regularly visited service stations in the Asheville area, particularly in Swannanoa and North Asheville. Observing interactions among Arab persons and their more formal interactions with outsiders/customers prepared me for our eventual meetings. Arab workers began to Jones 17 acknowledge my presence, so I legitimized my prolonged searches for the right snack by introducing myself as a student and researcher. Even after ‘legitimizing’ myself, most Arab workers were hesitant to speak with me. They were skeptical of my intention which was completely justified. Each time I presented my lay summary or began to talk about the research, I was met with: “Why do you want to study us? Why are you interested in Arab culture?” This was my initial frustration with the ethnographic research process. I remembered Ali and Anat’s advice and decided to visit the Islamic Center. I spoke with the Imam of the Islamic Center of Asheville, who introduced me to several Arab worshippers. I attended Juma prayers on several occasions to observe this Friday afternoon ritual; however, no formal interviews were conducted with mosque attendees. I communicated with several attendees via email which seemed to be the most fruitful approach due to their busy work schedules. I met one participant, Alon, at a bar in Downtown Asheville. He is a unique participant, because he takes the labels: Arab, Jew, Israeli, and Moroccan. I also informally interviewed Rusty, a middle-aged male from Swannanoa, who is employed at a local service station owned and managed by an Arab. Personal Research Context and Positionality Ever since childhood, I have been drawn to people of other ethnicities, particularly those from the Middle East. My grandmother remembers little about her immigration experience and seldom embraces her Syrian Christian heritage. I have observed persons of Arab descent at ‘Middle Eastern’ restaurants and cultural festivals for years; however, I and the rest of my family have always felt detached from the Jones 18 community. Hence, I wanted to understand how Arab persons construct new identities and preserve aspects of their home cultures when living in the United States. Initially, I was abhorred by some of my participants, who glorified the United States. I hoped Arabs would be very critical of the U.S., particularly regarding its foreign and immigration policies. These “hopes” exposed my own liberal biases and my privilege as a white, American male. I possessed a Marxist working class lens, where I expected Arabs to explain their plights as workers. My personal relationships with the study participants also posed a serious threat to the validity of this research. The initial interaction with most of the participants took place in a business setting with me, the researcher, playing the role of a customer/consumer. The study participants were careful to disclose information that could potentially influence my attitude toward their business. Preconceived Notions: Idealizing the U.S. Preconceived notions of life in the U.S. held by persons of Arab descent reflected the core ‘American’ values instilled upon our nation’s populace. Archetypal American discourses stress the values of individuality, freedom, and endless opportunity. The media reproduces these discourses through its depiction of “our” consumer culture which suggests resources are attainable to the masses. Most of the world is becoming Jones 19 increasingly Americanized, hence the aforementioned values are considered better than the ‘collectivist’ and ‘restrictive’ cultures of the East. The internalization of ‘American’ values acts as a catalyst in the process of integration, because immigrants come to the U.S. equipped with these desires. However, this does not mean immigrants have the resources to immerse themselves in a consumer culture upon arrival. Foreigners’ perceptions tend to reflect such hegemonic values, because the U.S. commercial sector markets itself according to this predominant discourse. Some participants were intrigued by the aforementioned notions of freedom and individuality. As Nada noted, “I was tired of my family’s expectations. They wanted me to marry a man from Lebanon, but I didn’t want that. I wanted to come to U.S. I want my own job and my own money. But, our culture looks down on that.” Her desire to lead an individualistic lifestyle reflects these hegemonic values and a Western influence on gender expectations. Nada’s strategic embodiment of individualism contributed to her rapid acculturation. Some could argue that she assimilated; however, Nada still speaks in her native tongue at home and cooks traditional Lebanese fare. Her language, particularly her expression “our culture,” suggests that she has not completely abandoned her ethnic identity. Upon his first visit to the States, Baha was impressed by the country’s enormity. He believed the nation’s sheer size was indicative of endless opportunities. Baha first visited the United States in 1992, when he was fourteen years old. He came to visit his grandfather, an American citizen, living in New Jersey. His father had just passed away, and Baha knew he would soon have to take financial responsibility of his family. After coming to the U.S., Baha was expected to maintain a reciprocal relationship with his Jones 20 relatives back in Jordan; however, he rejected his new role as the financial provider and lost the respect of many of his family members. Abandoning his role in the family exemplifies Baha’s integrationist tendencies, because this is often considered an American phenomenon. Baha still speaks Arabic in private settings, yet he impregnated an American woman and eloped in act of direct defiance toward his family. Baha arrived in the U.S. at a young age, which suggests he was not heavily indoctrinated into Jordanian culture. He also recalled being exposed to American cultural forms since early childhood. Baha described his preconceived notions of the U.S. and his first impressions of the country: “I thought this place was really big. My grandfather sent pictures to us in Jordan…I loved them, especially the ones from New York, but I didn’t know how great the U.S. really was. When I got here, I could not believe all of the freedoms! I was very impressed.” Baha uses the term “freedoms” which alludes to his internalization of an archetypical American discourse. His statement also shows that he was accustomed to seeing images from the States. Baha’s early introduction to quintessential ‘American’ images like the Empire State Building fostered a burning desire for him to emigrate. Advertisements and the media exploit and/or exaggerate America’s physical features to impress those from other countries. Few countries remain unscathed by the process of Americanization, particularly Jordan. Baha reflects the “American” values of freedom and endless opportunity, which are also part of Jordanian political rhetoric: I was watching T.V. one day…You know they have T.V. in Jordan, right? It was an ad for something…I don’t remember what it was for, but I remember seeing them Rocky Mountains and thinking about me being there. I always heard the U.S. was beautiful and open. I dreamed I would go there someday and find a good job. Now I live here [Swannanoa] and work at Subway. This is definitely not the Rockies. Jones 21 Baha begins by asserting his claim to modernity. The television seems to be a symbol of modernity and perhaps something that reflects socioeconomic status. Baha’s recollection demonstrates how the U.S. commercial sector appeals to foreigners, who sometimes feel confined by traditional social roles in their home countries. Space is also exaggerated to represent America’s seemingly endless expanses. Surely the depictions of America’s natural environments must correspond with the prospects for economic advancement in the States. Baha’s internalized the notions of ‘ruggedness’ and ‘vastness’ which helped him integrate into the host society. Motivations for Coming to the States Most study participants noted coming to the U.S. for economic reasons, which satisfies Jacoby’s (2004) notion of the quest for a better life. Many Arabs seem to be enchanted by the prospect of attaining great wealth in the United States, excluding those who come here for educational purposes. Baha stated, “It’s hard for a young guy to have an easy life in Jordan. There are jobs, but I had to support my family. I had to come to the United States to make more money, so I could support them.” Such enchantment led to above minimum wage-paying jobs as soon as Arabs arrived in the U.S. However, many of these jobs did not offer the prestige associated with living a “better life.” Trained professionals from the Arab World commonly take service sector jobs in the U.S., but they are not desired. Some participants took whatever jobs they could get at first. Rafiq recalls his situation: I knew there were jobs here. My family told me about jobs in America, mostly in trade and stuff like that. My uncle and cousins come here about Jones 22 six years ago, and they got jobs pretty fast. I think they worked at Exxon station and some markets. Now they own a franchise in New Jersey. They told me I would not have trouble with jobs. I found one really fast, but it wasn’t what I learned to do in Jordan. I took the first one, even though it wasn’t accounting job. Chain migration from the Middle East appears to be the norm, with immigrants making it possible for the economically ambitious in their home countries to seek newer horizons. The informal “indoctrination process” occurs when “significant others,” particularly family members, friends, and community leaders, “attempt to pass on their perceptions of life in [the United States] to the new initiate” (Hayani 1999: 289). This process is similar to the relationship between Baha and his grandfather, who sent pictures of the U.S. back to the Middle East. Baha’s grandfather brought him to the States; however, his socially conservative perceptions were not passed on to his defiant grandson. Family members and friends with business connections played a critical role in constructing the futures for “boaters.” This slang term refers to newly arrived, oftentimes conservative immigrants (Shryock 2002:918). Building social capital increases the likelihood of emigrating and becoming financially stable upon arrival. In the words of Habid: “My father’s friends got a job for me in New Jersey. I worked at a food distribution warehouse. I didn’t like the job very much, because I am not used to doing that kind of work.” Habid’s story emphasizes the importance of social networking. Large social networks exist in the Arab communities of the Northeast; however, Asheville’s Arab population is dominated by a few individual families. Most of these families own franchises throughout Western North Carolina and rarely interact with one another. Hence, Arabs who come to Asheville and do not have ties with these families Jones 23 (as in the case of Baha) integrate into other social groups. Nada, who left her nuclear family back in Lebanon to attend college in the States, had considerable social networks upon her arrival. Before moving to Charlotte, several of her extended relatives lived in the Asheville area and had created long-lasting business connections. These bonds enabled her to get a job at a service station that was not hiring and help her finance her classes at a local community college. Nada commented on her advantageous connections: I knew my relatives would take care of me. I came to the U.S. with very little money. I barely knew anyone, but family connections are strong. This is probably the only reason I was able to find a job. I don’t know what I would do without their help. Observations suggest Arab-dominated franchises in the area are the result of familial ties and social networking. These ties and networks are examples of Hayani’s pre-contact characteristics. Nearly every Subway in Western North Carolina is owned by the same Jordanian family, hence a “localized monopoly” on healthy, fast-food sandwiches has been revealed. Economic success depends upon the maintenance of familial and social relations which create “immaterial” and “non-economic” capital (Bourdieu 1986). However, no single, overarching community seems to exist for Arabs living in the Asheville area. On Being ‘Arab’ in Asheville… Negotiating the Term ‘Immigrant’ Arabs living in Asheville are reluctant to internalize the term ‘immigrant.’ The term’s ostensibly negative connotation posed many challenges to the research process. A number of participants were instantly disinterested in this research after they read the Jones 24 term in my lay summary. Some could argue, immigrant, has a more positive connotation than the word, illegal alien. But, both labels are often used to describe nonwhite, working class, nonnative English speakers. ‘Immigrant’ also suggests a sort of permanence which intimidates some Arabs, especially those hoping to return to their home countries. Dropping the word ‘immigrant’ in conversation was seen as a derogatory remark by some Arabs. Most participants rejected the label, because many of them are temporarily living and working in the States. Brettell’s (2000) typology discriminates between different immigrants: those who intend to stay temporarily and those who plan to stay permanently. Arabs living in Asheville seem to reject this label, because many are from the middle strata of their home societies. In fact, many have university educations and leave their countries for economic reasons. But despite their class origin and education, many take service industry jobs in the U.S.. Ali comments on this phenomenon: “I did not come to U.S. to make money. I came here for my sons and their educations, not for me and my wife. We have to work at our restaurant a lot of days. I should be retired by now if I stayed in Alexandria [Egypt]. We had good lifestyles there.” Ali challenges Jacoby’s notion of a “better life.” After changing the summary’s language, potential participants were still skeptical of the term ‘immigrant’ if it came up in conversation. After I dropped the term, Ali seemed insulted and slyly refused to answer any additional questions: I’m not immigrant! I’m way too old. I come here for my sons, that is all. You [the researcher] should talk to younger boys like my sons. They are the real immigrants. I am not what they call immigrant. They have their education in the States and they speak the best English. Ali exposes several reoccurring aspects of Arab identity in this brief statement. He Jones 25 rejects being called an immigrant from the outset and appears offended for having been deemed so. Importantly, age emerges as a factor in determining one’s status as an immigrant. He acknowledges his role in the service industry, yet he does not accept the label of “immigrant.” Predominant discourses often refer to immigrants as laborers yet he challenges this notion. Ali describes children as the “real” immigrants. He was specifically referring to his sons, who were educated in the U.S. Other participants were quick to mention their children’s better understanding of “American culture.” Apparently, true ‘immigrant’ status reflects the extent to which Arabs internalize the values and cultural forms of their American counterparts. Habid cites his noninvolvement with his children’s schooling and a misunderstanding of popular trends: My childrens know more English than I do. They bring homework that only they know. I should know this, but I have not been to school for a while. I don’t understand their grades so much, but they will go to college. That’s what their teacher says anyway. I think they won’t go to college if they keep listening to this Black music [referring to hip hop and gangster rap] and playing around after school. Pre-contact considerations, such as age and education, emerge as the focuses of Habid’s discussion of ‘immigrant’ identity. According to Hayani, “…education provides a person with the knowledge, language, conceptual skills, and problem-solving tools that enable him or her to deal better with the demands of acculturation” (Hayani 1999:289). Older Arabs differentiated themselves from their offspring, who possessed better English skills and were in touch with popular culture. This shows a construction of identity in which parents are motivated by the desire to improve their childrens’ lives, even if this means abandoning themselves to the fact that their children will have different identities. First-generation Arabs do not embrace the “immigrant” label, simply Jones 26 because it is attached to their papers. Their temporary statuses also serve to resist this label. From an etic perspective the label is predetermined; however, the term appears to mean a lot more to the individual. Those perceived to be immigrants are often seen as social and economic threats to native-born citizens. Locals often equated Arabs to Latin American immigrants, who are perceivably “stealing peoples’ jobs.” Rusty, a white, middle-aged male describes his Arab boss at a service station in Swannanoa: Those people are starting to buy up the whole place. You take a business on 70 and one of them owns it. It doesn’t matter where they are from, India or the Middle East, they want to buy whatever businesses they can…I mean…I like my boss, but he’s always on his cell phone. I don’t know what he talks about, probably something bad about this country. Rusty alludes to the negative sentiments held by some locals about Arab peoples: “He just doesn’t fit in here. I don’t know why he wants to live in Swannanoa with a bunch of us.” (I assume he used the term “us,” because my outward appearance does not suggest my relatives are from the Middle East.) These statements provide key insights into the “othering” process. Ethnic differences are interpreted as a threat to the supposed monoculture of Swannanoa. The Lack of a Young Arab Community Arabs living in Asheville swiftly acculturate due to the city’s lack of pluralism. The city lacks pluralism on many levels, particularly concerning race and ethnicity, which inhibits the formation of sizable, ethnic groups. Social networks expanding beyond the family are mostly confined to older, first-generation Arab males. One restaurant in downtown Asheville serves as a meeting place for mature Arab men, who gather to talk about business and politics. (I was advised never to sit in on these Jones 27 meetings.) Such networks occasionally reach out to younger Arabs, as in the case of Nada and Habid; however, no substantial social groups have been organized for young Arabs. The city’s lack of young, Arab social groups encouraged one participant to become involved with an underground youth culture. Gordon (1964) suggests an immigrant is not participating in the host society until people with different ethnic backgrounds socialize together, visit each other, and belong to the same social clubs. His theory concerning immigrant participation is more assimilationist than acculturationist in its approach and is not really applicable within the Asheville context. Alon spoke to me about the intensification of his drug habits after socializing with his “downtown” friends at BoBo’s: In Israel, I used to take drugs, but never like I do here. I mean…I drank in Israel, but I rarely did other drugs. I think Asheville has a considerable drug culture and many in our community take advantage of that. I could not get away with this many drugs in my home country, because I lived with my parents. Now that I live on my own, I can do whatever I want, whenever I want. There aren’t any hookah bars or places for Arab people to hang out, so they do what everyone else is doing. In Asheville’s case, that is drugs. Seemingly, younger Arabs take on the habits of their ‘Ashevillian’ counterparts. Alon said his party habits would be different if community organizations existed for Arabs to get together and share their experiences in the host society. He also stated, “…many Arabs lose touch with their heritage, because Asheville is so small, and there is no diversity here. I used to live in New York, where I would see hundreds of Arabs everyday.” He leaves me wondering if young Arabs feel a sense of community in New York, simply because it is an extremely diverse city. Jacoby (2004) assumes second-generation immigrants do not seek to lose their Jones 28 cultural heritage like early immigrants. Asheville’s lack of pluralism, particularly in regard to Arab communities, challenges Jacoby’s notion of preserving cultural heritage. Young Arabs found it difficult to maintain their cultural identities in the absence of large ethnic groups. Second-generation Arabs felt that maintaining relationships with other groups was more important (as in the case of Alon). Marginality within Asheville’s Arab Population Arabs have been the targets of much scrutiny, especially after September 11, 2001 and the current ‘wars on terror’ in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mainstream media assume the Arab or Islamic origin of anyone accused of a terrorist act. The Middle East is also portrayed as a land of “radical fundamentalists.” In effect, the media has demonized Arabs and labeled Muslims as social deviants. When the media portrays Arab communities in the U.S. they often turn to Yemeni neighborhoods, which are perhaps the most conservative and visually “exotic” (Shryock 2002:918-19). Highly visible Arab communities, particularly those surrounding Detroit, arguably experience the highest levels of discrimination within the American context. Prior to September 11th, 2001, Arab immigrants felt comfortable inside their relatively safe, “clean,” Detroit neighborhoods. After the terrorist attacks, Arabs described their own neighborhoods as “ghettoes” and “enclaves.” “A resurgent imagery of Otherness and marginalization, increasingly Muslim in focus, is now the backdrop against which Arabs in Detroit are struggling to (re)define themselves as ‘good citizens’” (2002:917). This is not the case within the Asheville context. Arab and Muslim populations are very small, and there are no distinctively-Arab communities or neighborhoods. Even though Jones 29 Asheville flaunts a façade of acceptance and liberality, Arabs have been marginalized, notably by other Arabs. Several Arab participants associated the term “immigrant” with local Palestinians, who generally hold service sector jobs in the local economy. The word seems to carry a stigma, because immigrants, or Palestinians (the participants used the two terms interchangeably), are associated with lower/working class populations. Interestingly, Arab professionals and religious leaders relayed these stereotypes. Palestinians seem to accrue marginal statuses within the Arab community. At the Islamic Center, Abdel noted: Abdel: I bet you have run into Palestinians in your research at gas stations. Me: No, I have met several Jordanians, who have been very helpful. A: Well that’s a surprise, because they are not really Jordanian. They are dirty Palestinians, but they won’t tell you that. They want you to think they are not from a conflict area. They also never come to mosque, which I think is very bad reflection of their characters. The de-emphasis of Arab and Muslim backgrounds suggests my participants were careful in expressing their ethnic identities, perhaps to avoid confrontation or discrimination. Ali alludes to this, but he did not expand any further on this subject: “I say Middle Eastern food instead of Arabic food, because it will reach a greater section of the population. I think if people saw ‘Arabic,’ they would not understand what it is. Sometimes people come to me asking for Greek food. This is only somewhat similar.” Other Arabs living in Asheville downplay their “Arabness” as well. Nada downplays her “Arabness” by refusing to dress in Muslim garb. She wears “revealing clothes, because [she] likes the way they make [her] feel.” Nada’s love of “provocative” clothing rejects the Islamic norms and values on which she was raised. Besides the negative perceptions of Palestinians projected by other Arabs, participants recalled few discriminatory Jones 30 experiences while living in Asheville. In fact, a South Asian immigrant, who owns a local hotel, said he experienced more discrimination in New York than while living in Asheville. Conclusion: Integrating into “Ashevillian” Culture Most participants took bites of “Ashevillian” culture and maintained their cultural identities to some degree or another. Both are pursued simultaneously which leans toward the integrationist mode of acculturation. Behaviors and familial roles reflect home country norms and values, especially in the case of older Arabs like Ali. Younger participants like Nada and Baha also uphold traditional Islamic values and embrace Arab cultural forms at home. However, their public representations of identity reflect a readiness to accept new cultural forms. One should remember Nada’s strategic embodiment of individualism, where the internalization of ‘American’ values aided the process of integration, or Alon’s participation in Asheville’s drug culture, which he blamed on the lack of pluralism in the city. Second-generation Arabs felt that maintaining relationships with other groups was more important than fostering their cultural heritages. This presents an interesting dichotomy between older and younger, or first and second-generation, Arab immigrants which should be researched in greater depth. This research turned out to be a collection of case studies as opposed to a broad ethnographic inquiry into an organized community. Arabs living in Asheville generally lacked a connection to one another, and most of their stories were unique. It was difficult to draw parallels between participants’ stories; however, many commonalities emerged, Jones 31 especially concerning the motivations to emigrate and preconceived notions of the United States. I now understand why most research concerning the construction of Arab identity has been conducted in large cities like Detroit and Chicago. After all, there are no Arab organizations in Asheville. The gender dynamics at the Islamic Center also prevented me from interacting with women, and the men (although very friendly) were committed to their business lives. References Cited Berry, John W. 1990 The Role of Psychology in Ethnic Studies. Canadian Ethnic Studies 22(1):132. Bourdieu, Pierre 1986 The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. John Richardson, ed. Pp. 241-258. New York: Greenwood Press Brettell, Caroline, B. 2000 Theorizing Migration in Anthropology: The Social Construction of Networks, Identities, and Globalscapes. In Migration Theory: Talking Across the Disciplines. Caroline B. Brettell and James F. Hollifield, eds. Pp, 97-136. New York: Routledge. Jones 32 Glazer, Nathan 2004 Assimilation Today: Is One Identity Enough? In Reinventing the Melting Pot. Tamar Jacoby, ed. Pp. 61-73. New York: Basic Books. Gordon, Milton 1964 Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press. Hagan, Jacqueline Maria, and Helen Rose Ebaugh 2003 Calling Upon the Sacred: Migrants’ Use of Religion in the Migration Process. International Migration Review 37(4):1145-1161. Hayani, Ibrahim 1999 Arabs in Canada: Assimilation or Integration? In Arabs in America: Building a New Future. Michael Suleiman, ed. Pp. 284-303. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Jacoby, Tamar 2004 Defining Assimilation for the 21st Century. In Reinventing the Melting Pot. Tamar Jacoby, ed. Pp. 3-16. New York: Basic Books. Joseph, Suad 1999 Against the Grain of the Nation--The Arab. In Arabs in America: Building a New Future. Michael Suleiman, ed. Pp. 257-271. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Moore, Kathleen 2002 A Part of US or Apart from US?: Post-September 11 Attitudes toward Muslims and Civil Liberties. Middle East Report 224:32-35. Samhan, Helen Hatab 1987 Politics and Exclusion: The Arab American Experience. Journal of Palestine Studies 16(2):11-28. Shryock, Andrew J. 2002 New Images of Arab Detroit: Seeing Otherness and Identity through the Lens of September 11. In American Anthropologist 104(3):917-922. Suleiman, Michael 1999 Introduction: The Arab American Experience. In Arabs in America: Building a New Future. Michael Suleiman, ed. Pp. 1-21. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. U.S. Census Bureau 2000 State & County QuickFacts: North Carolina. Electronic document, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37000.html, accessed April 5, 2007. Jones 33 Appendix A Interview Questions 1.) Tell me the story of how you happened to come here to Asheville? Begin back in Egypt/Syria/Jordan/etc. before immigrating was even a consideration. 2.) How did the media in your home country represent the United States? How did these representations (if any) influence your previous notions of life in the States? 3.) What has it been like for you to immigrate to the United States? What do you like? What do you dislike or find challenging? 4.) What kinds of activities (religious, family, work, social, etc.) do you do over the course of a typical week? Did you do the same kinds of things in your home country? *Provisional 5.) What does being an Arab Muslim mean to you? In what ways do you think your religion has influenced others’ perceptions of you? How has Islam shaped Jones 34 who you are? 6.) Do you feel a connection to other Arab immigrants? What kinds of things unite you? What kinds of things keep you separated? Subsidiary Interview Questions -Is there tension between new and old immigrants or animosity between children and their parents? -Do you think Arabs in Western North Carolina immigrate for the same reason? -In your opinion, does knowledge of the English language contribute to a better life? -What does “acculturation” mean to you? How does Asheville’s small size influence these modes of acculturation? -Does a community exist among Arab immigrants living in Asheville? Are there any leaders? -How do second-generation Arab immigrants preserve their ethnic and cultural identities? -How many Arab immigrants living in the Asheville area have dual citizenship? How might this influence the preservation of one’s ethnic identity?