IE 572

advertisement

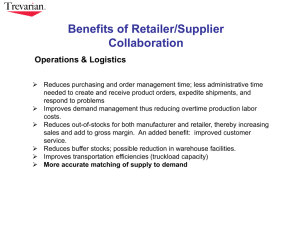

IE 572 Production Planning Systems Design Research Proposal “Quick Response And Accurate Response Systems” by Evren Körpeoğlu Bilkent University Industrial Engineering Department May 16, 2003 Introduction In today’s global world, many of the business environments face the difficulty of a continuous competition against the other firms in their sector. This competitive surrounding force these companies to look for new ways to increase their profits and more importantly they try to survive this challenge. These new ways include technological developments, new production systems, information sharing and methods to improve forecasting abilities. Fashion-apparel industry is one these environments which faces many problems. Its market and customers demand new fashionable items continuously. Lead times are too long, so forecasts should be done a long time before the season starts and eventually the forecasts are very speculative and inaccurate. This leads to either high inventory levels or product stockouts that cause loss of good will of customer and most of the time customers become dissatisfied. Another problem of the companies in developed countries is the cheap labor in developing countries. Since labor costs are very low in developing countries, they have a great deal of competitive advantage and they have the ability to sell the products at lower prices. In order to deal with these problems, companies in textile or fashion-apparel business tried many methodologies. Quick Response systems and Accurate Response issue are two of the method those are used to achieve a better competitive position in this sector. In addition, using these two systems together in different scenarios may be more beneficial then applying only one of them. In this paper, a methodology to implement and apply both of these techniques is discussed and a model for integration of both systems is considered. First it is appropriate to give brief information about Quick Response, Accurate Response and their possible benefits in industry. Quick Response Systems Quick Response is the establishment of new business strategies, new relationships and new procedures to speed the flow of information and merchandise between retailers and manufacturers. In other words, as Fisher and Raman stated (1996) “Quick Response is an apparel industry initiative intended to cut manufacturing and distribution lead times through a variety of means, including information technologies such as electronic data interchange, point of sales scanners, and bar-coding, logistics improvements such as automated warehousing and increased use of air freight, and improved manufacturing methods, ranging from laser fabric cutting to reorganization of sewing process in to modular sewing cells.” As the definition mentions, Quick Response is a holistic approach including nearly all the steps of manufacturing and distribution and tries to improve the system in the direction that the managers of fashion companies would want. Quick Response implementation is a long and difficult process and all the echelons of the supply chain must be willing to contribute to this improvement since it is a development concerning all the levels of the channel. In the apparel and textile manufacturing level, the necessary developments include using CAD systems for high-quality design, narrowing assortment before season by consumer style testing and limited introductions, helping retailer customers plan store assortments down to full SKU, implementing quality control programs to avoid duplication of effort and replacing adversarial customer and supplier relationships 1 with cooperative partnerships. In the retailers case, they should plan the assortments by individual store characteristics, rather than aggregate chain requirements, manage inventory and re-ordering by store rather than overall system and share sales data and other key information with suppliers and manufacturers. Technological developments and using them in appropriate places is an important step of Quick Response implementation. These technologies are Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) which creates an online linkage between retailers and suppliers and make them share information continuously, Shipping Container Marking (SCM) which is the bar-coding process of container and by this way retailer can easily manage the amount of incoming goods to the stores, Bar-coding of the fashion items, Computer-Aided Design (CAD), Unit Production Systems (UPS) which automates the movement of products in the manufacturing environment, Flexible Manufacturing equipment including electronic pattern making and laser-based cutting, Electronic Reorder, Line Planning System (LPS), Development Calendar System, Computerized Inventory systems and short cycle sewing. All together, these technologies help firms have the benefits of a Quick Response system. There many possible benefits of a Quick Response system. First of all, there is a great reduction in lead times both in production and in transportation. Reduced lead times create a decrease in inventory levels since safety stocks levels decrease and overall inventory costs become smaller. It makes the market share bigger and enhances the customer loyalty because of less stockouts. Quick Response improves flexibility to meet changing market demand because of the reduced lead times and increases productivity of the manufacturing environment with all the technological implementations. Thus, all of these improvements generate an increase in profitability of the company. However, as Brown et Al. declare, “Firms attempting to pioneer in product/market development, benefit most from quick response. These firms tend to offer a frequently changing product line and compete primarily by stimulating and meeting new market opportunities. They are also creators of change and uncertainty to which competitors must respond.” Accurate Response Accurate Response is a new approach to decrease the forecast accuracy by dividing the period into two or more small periods and making the orders after first sub-period with the information gathered and demand estimated in that period. The procedure is very simple; first with an inaccurate demand estimation which made long before the season is used to estimate the demand in the sub-period 1. An order of Q1 is issued according to this demand information. Then, after the period started, the company begins to collect the real demand data and make a new forecast with this actual demand information. Thus, the second forecast is much more accurate than the previous one and using this new forecast to estimate Q2 gives very accurate results and decreases the amount of inventory leftovers and stockouts. Although it seem there are two decision variables to decide, Q1 and Q2, before the season begins, only Q1 should be determined. Q2 should be determined in mid-season and with the demand information gathered throughout the season. However, it is essential to coordinate the determination of Q1 and Q2. Q1 can be determined correctly only if all the Q2’s possibilities are fully considered. The inventory surplus from the first season should be considered before determining the order amount for sub-period 2. Because if surplus is greater than the expected 2 demand in second part of the season, then it is unnecessary to make and order or if it is zero, all the expected demand should be reflected to the order. Some benefits of the accurate response is as follows: accurate forecasts related with the data gathering in the season, reduced mismatches between supply and demand, lower costs, increased profits and lower average inventory levels. In addition to these, since service level is increased and stockout amounts are reduced, customers will be more satisfactory than the previous applications. Literature Review Hammond (1991) explains the concept of Quick Response in apparel industry in a detailed manner. He includes necessary technological implementations, required duties of companies in different supply chain levels, the development and progress steps of methodology and possible echelon company types of a Quick Response system. Thus, this paper is an excellent reference to understand the main concept of Quick Response. Brown et Al. (2000) examine the effect of business type while implementing a quick response system and conclude that prospectors have the most benefit. Moreover, they investigate three stages of companies beginning to use the Quick response process: persuasion, decision and implementation. Perry et Al. (1999) describe the processes occurred during the implementation of quick response program to the textile, clothing and footwear (TCF) industry applied in Australia funded by Australian government. They give twelve steps to implement a quick response supply partnership development and real world example is discussed in the light of these twelve steps. Perry and Sohal (2001) investigates the benefits pf the companies gained by the implementation of QR program in Australia and the study includes the comments of managers of different TCF companies. Iyer and Bergen (1997)’s paper was one of the first articles that has an analytical approach to the effects of Quick Response. They investigate the effects of reduced lead times, which is achieved by QR, on a single period problem. They saw this system was always beneficial for retailer but for manufacturers if service level is less than 50%, it increases the profits. They suggest ways to increase the profit of the manufacturer to make the channel Pareto improving such as total minimum volume commitments, different service level issues and wholesale price adjustments. However, in their research, the manufacturer cannot change the wholesale price (w) and does not accept returns from the retailer. Moreover, the retail’s sales price is fixed (p) and retailer does not have the change to change the price. Lau HS and Lau AHL (1999) consider the impact of demand uncertainty in single period problems where manufacturer determines both wholesale price to retailer (w) and return credit amount (r). They find out that, as the demand uncertainty decreases, the profit of manufacturer increases, but profit of retailer decreases, at a certain wholesales price level (w), retailer may have nearly zero profit, and so the manager of the retailer may not be willing to sell the product. To prevent this, some constraints for retailer profit are considered and retailer has at least a predetermined amount of profit. However, these results also depend on their 3 willingness to take risk coming from demand uncertainty, because it is stated that main source of retailer’s profit is taking demand uncertainty risk. Thus, if retailer doesn’t take risk and manufacturer makes demand uncertainty too low, then using a retailer will not be necessary anymore. Lau HS and Lau AHL (2000) add the issue of valuation uncertainty to their previous research and examine customer demand uncertainty. Valuation uncertainty is the indefiniteness of sales price of the retailer and the value of the fashion goods to be sold and it makes the single period problem even more complex. Khouja (2001) examines the effect of large order quantities on the single-period problem. Due to the auto-correlation between the current season and following season, if the retailer order too much in this season and have discounted sales near the end of season, this will create a reduction on the demand of next period. Because for some item types, customer that purchase this necessary items in this season will not buy it in the next season. In addition to this, some customers may only purchase the item in discounted price, so a great deal of demand reduction can be observed in the following season. Lau HS and Lau AHL (2002) tries to expand the paper of Iyer and Bergen (1997) and their own paper in 1999 by including manufacturer’s wholesale price to retailer (w), return credit amount paid per unit (r) and retailer’s sales price (p) as decision variables. If wholesale price is high, then order quantity will be smaller. However, if demand uncertainty is low, then order quantity of the retailer will not be sensitive to the wholesale price. Explanation is simple; if variance is small then to meet the necessary service level requirement; retailer has to purchase the amount of product close to the mean of the demand. However, this paper assumes no coordination between parties; so, channel coordination may give better results both for manufacturer and retailer. Following table summarizes their findings (α is the price sensitivity of the customers): Decision Variables Fixed-value Variables Q w, r=0, p ∂M/∂σ < 0 if SL < 0.5 > 0 if SL > 0.5 ∂R/∂σ ∂T/∂σ < 0 always < 0 if SL > 0.5 > 0 if SL < 0.5 depends on p , depends on p , π , < 0 always π,s s Q,w r=0,p Q,p,w r=0 < 0 in most cases < 0 in most cases < 0 (high α) > 0 (low α) w,r,p,Q - < 0 (high α) < 0 in most cases < 0 (high α) > 0 (low α) > 0 (low α) 4 Next, the literature about Accurate Response comes. Fisher and Raman (1996) are the first academicians to consider the accurate response. They analyze accurate response and provide a methodology for performing this more complex response-based production planning. They consider multi-product case and they try to allocate production and ordering across two subperiods; given the predicted early forecast error of each product. Correlation between first and second sub-periods is found, since this correlation is the basis of this study. A method to estimate demand of first sub-period is proposed and with this method the order quantity for the sub-period 1 is assumed to be estimated in a good manner. Since there is limited capacity for the production for second sub-period, a capacity constraint is used. Minimum product lot size is used to make setups and fixed cost feasible because giving an order which is very small although setup costs are high is infeasible. At the end of the paper, they gave the results of a real life example, Sport Obermeyer case, and the results of the study were impressive. Lau HS and Lau AHL (1997) consider the reordering strategies for a single-period problem. Normal and Beta demand distributions are considered. Order quantity for sub-period 1 (Q1) is always less than total order quantity without accurate response (Q) and profits with accurate response is always greater than profits without it. For same retailer’s cost values, as demand uncertainty increases, the ability to delay ordering decisions become more valuable meaning that dividing the season into two periods and making orders later becomes more important. Percentage increase in expected profit increases with the (c/p) ratio and it decreases as the profit margin decreases which is sales price minus the cost per unit (p-c). Because a small profit margin mean that retailer does not have a satisfactory profit so accurate response losses its importance. Percentage increase in Total Volume is negative for small c-values but positive for larger c. Lau HS and Lau AHL (1997) investigate the same conditions above with uniform demand distribution and get similar results. Donohue (2000) try to develop supply contracts that encourage proper coordination of forecast information and production decisions between manufacturer and retailer operating in a two-mode production environment. The first mode is a slow mode which requires a long lead time and second one is a fast mode (Quick Response) with a short lead time. He tries to increase the overall profitability of the channel using some supply contracts and makes his study in an environment where a single period is divided into two or more sub-periods similar to previous research. Milner and Rosenblatt (2002) analyze a two-period supply contract which allows for order adjustment by the buyer or the retailer. The buyer is required to place orders for two subperiods. After observing initial demand, the buyer is then allowed to adjust the second order, paying a per unit order adjustment penalty. They describe the optimal behavior of the buyer under such a contract, both in determining the initial order quantities and in subsequently adjusting the order and compare the solution to a contract where no adjustment is allowed and to the case where adjustment is allowed without penalty. They demonstrate that flexible contracts can reduce the potentially negative effect of correlation of demand between two periods. 5 Model Proposition In my research, I tried to integrate the benefits of Quick Response and Accurate response systems to achieve even more accurate forecasts and decreasing inventory levels and customer dissatisfaction. My specific research question can be: “How can we integrate Quick Response and Accurate Response in order to increase the forecast accuracy for single-period items?” More specifically, my research consists of a single period divided into two sub-periods. Before sub-period 1, the retailer decides on the amount of order to be placed (Q1) and order quantity for sub-period 2 (Q2) will be determined in mid-season. There are two alternative pricing options in the model. Q1 has a cost of c1 and has a long lead time and Q2 has a cost of c2 and has a much shorter lead time. Eventually, c1 is less than c2 to make the problem feasible. Q1 should be predetermined by some forecasting methods or information taken from other companies and an order should be issued long before the season begins since the lead time of Q1 is long and the order should arrive before the season begins. After the season begins, the retailer starts to collect the actual demand data and create a new demand distribution based on actual information as soon as possible. For the ordering phase of the second sub-period, it is appropriate to use Quick Response to reduce the lead time and receive the order as quickly as possible. Moreover, since the approximate lead time of the Quick Response manufacturer is known and the retailer has a realistic demand distribution, the demand during lead time can be estimated. Using a continuous or periodic review, when inventory level is less than the safety amount plus the demand during lead time, second order will be issued and since second sub-period’s length and demand distribution is known, very accurate demand evaluation can be made. To formulate the model some alternatives can be thought. First of all, assuming a normal distribution will be appropriate because of the common stochastic behavior of all the industrial environments and markets. We have two distributions: a normal distribution before the season which has a large variance and a second normal distribution which is determined after the season begun and which has a smaller variance. Since we do not know the exact length of the sub-periods, the demand during these sub-periods will be related with the time concept and the possible length of the season. To find the demand in the first sub-period, an estimated length for this period can be used and the distribution can be multiplied by this length to find the demand. Before the second sub-period, since we know the remaining time to the end of the season, it will be easier to estimate the demand in the second period. So, time intervals of the periods will not be deterministic and the effects of this should be reflected to the formulation. With the help of the formulation in Donohue’s paper (2000), I tried to develop a formulation for my model. However, this formulation may have some mistakes since it was not a result of an academic research and it was not thought carefully. But, it may give some insight about the situation about the proposed model. The following is my formulation which assumed to reflect the model: 6 Max (Q1 | c1, c 2, r ) (c2 - c1)Q1 Q1 0 H(d , Q1) f (d )d , d 0 Where H(d, Q1) Max h(d , Q1) Q Q1 h(d , Q1) c 2Q d x 0 x d (px r (Q x)) f ( x | d )x ( pQ s( x Q)) f ( x | d )x In this formulation; c1 c2 Q1 Q2 Q p r s : cost of ordering for first sub-period : cost of ordering for second sub-period : order amount before sub-period 1 : order amount before sub-period 2 : Q1 + Q2 : sales price of the retailer per unit : return credit per unit : shortage cost per unit First of the possible results of the model is, in the optimum solution, Q1 will be as large as possible because of less ordering cost (c1<c2). There won’t be any surplus left from subperiod 1, unless Q1 is greater than the total demand of season which is like the Lau and Lau’s case (1997). Overall profit of the system will be increased before of reduced inventory levels and since Q2 is accurate, inventory leftovers and stockouts will be reduced and costs associated with these (holding and stockout costs) will be minimized. Future Research Directions In my research, I tried to examine a new point in both Quick Response and Accurate Response issues. But, since this subject is relatively new there are many other possible research aspects related with it. c1 and c2 can be variable. (manufacturer can determine these values) Effects of ordering with QR before sub-period 1 can be examined. Capacity of the manufacturer can be considered before ordering Q2. Lot size issues to make both orders can be considered. Multiple sub-periods can be used. 7 Conclusion As a conclusion, in this competitive world, where each firm or company search way to survive, it is necessary to find some methods to give them a competitive advantage. Quick Response systems, which aims to decrease lead times using many technologies such as information or improved logistics and accurate response systems, which aims to have accurate forecasts and reduce supply demand mismatches, could help them achieve this important mission. The research papers I examined show that these methods really have great impacts on the companies in a positive way, even if, they sometimes require a great deal of investment on technology and some other stuff. Thus, firms should be willing to implement these systems without losing time to gain their benefits and to make themselves stronger against the other companies. Many research, which aims to integrate these two systems gives an insight about how they can be used together and since both of these systems are beneficial, this research will be useful in every means possible with Quick and Accurate Response. Further research issues can be considered to have a better model and to have many other benefits by examining other possible environments. 8 References Brown, J., Kincade, D. and Ko, E. “Impact of business type upon adoption of quick response technologies” International Journal of Operations & Production Management Vol.20 No.9, 2000: 1093-1111. Donohue, Karen. “Efficient Supply Contracts for Fashion Goods with Forecast Updating and Twp Production Modes.” Management Science Vol.46 No.11 (2000): 1397-1411. Fisher, M. and Raman, A. “Reducing the cost of demand uncertainty through Accurate Response to early sales.” Operations Research Vol.44 No.1 (1996): 87-99. Hammond, J. H. “Quick Response in Apparel Industry.” Harvard Business School Note N9-690-038, Cambridge, 1991, Mass. Khouja, M. J. “Optimal ordering, discounting, and pricing in the single-period problem.” Int. Journal of Production Economics 65 (2000): 201-216. Khouja, M. J. “The effect of large order quantities on expected profit in the singleperiod model.” Int. Journal of Production Economics 72 (2001): 227-235. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “A semi-analytical solution for a newsboy problem with midperiod replenishment.” Journal of Operational Research Society 48 (1997): 1245-1253. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “Comparative normative optimal behavior in two-echelon multiple-retailer distribution systems for a single-period product.” European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003): 659-676. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “Demand uncertainty and returns policies for a seasonal product: An alternative model.” Int. Journal of Production Economics 66 (2000): 1-12. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “Manufacturer’s pricing strategy and return policy for a singleperiod commodity.” European Journal of Operational Research 116 (1999): 291-304. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “Reordering strategies for a newsboy-type product.” European Journal of Operational Research 103 (1997): 557-572. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “Some results on implementing a multi-constraint single-period inventory model.” Int. Journal of Production Economics 48 (1997): 121-128. Lau, HS and Lau, AHL. “The effects of reducing demand uncertainty in a manufacturerretailer channel for single-period products.” Computers & Operations Research 29 (2000): 1583-1602. Lin, Chen-Sin and Kroll, Dennis E. “The single-item newsboy problem with dual performance measures and quantity discounts.” European Journal of Operational Research 100 (1997): 562-565. Milner, J. and Rosenblatt, M. “Flexible Supply Contracts for Short Life-Cycle Goods: The Buyer's Perspective.” Naval Research Logistics 49 (2002): 25-45. Perry, M., Sohal, A. and Rumpf, R. “Quick Response supply chain alliances in the Australian textiles, clothing and footwear industry.” Int. Journal of Production Economics 62 (1999): 119-132. Perry, M. and Sohal, A. “Effective quick response practices in a supply chain partnership: An Australian case study.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management Vol.21 No.5/6 (2001): 840-854. Richardson, James. “Vertical Integration and Rapid Response in Fashion Apparel.” Organization Science Vol.7 No.4 (1996): 400-412. 9