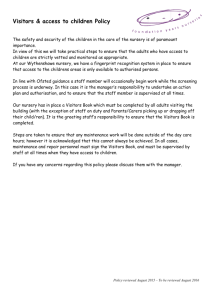

chapter 2: participation begins with me

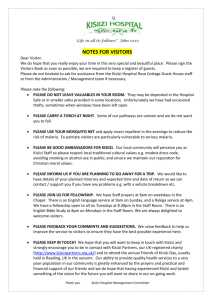

advertisement