The World Bank and Environmental Assessment (EA)

advertisement

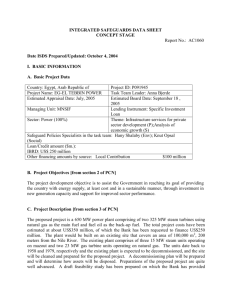

The World Bank and Environmental Assessment (EA)1 Jean-Roger Mercier Draft Wednesday, March 09, 2016 c.j.bastmeijer@uvt.nl Timo.Koivurova@ulapland.fi Table of contents The World Bank Group and its activities ........................................................................... 2 History............................................................................Error! Bookmark not defined. Environmental Assessment of Investment Projects ............................................................ 2 History............................................................................................................................. 2 Intent and Content ........................................................................................................... 3 Outcome of the EA process ............................................................................................ 4 The institutional context ................................................................................................. 6 New challenges ............................................................................................................... 6 Environmental Assessment of Policy Reforms, Plans and Programs ................................. 6 History............................................................................................................................. 6 Intent and Content ........................................................................................................... 7 Outcome of the EA process ............................................................................................ 7 The institutional context ................................................................................................. 7 New challenges ............................................................................................................... 7 A focus on Transboundary Environmental Assessments.................................................... 7 Origin and nature of TEA ............................................................................................... 7 Case studies ..................................................................................................................... 7 Lessons learned ............................................................................................................... 7 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 7 1 The views expressed in this chapter are those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank The World Bank Group and its activities The World Bank Group lends and provides technical assistance to developing countries and those in economic transition. It also manages grant funding, for instance from the Global Environmental Facility (GEF). The World Bank Group is made up of five organizations, (i) the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which was established in 1945 and has as its clients middle-income country governments, (ii) the International Development Association (IDA), which was established in 1960, and which provides credits to poorer client country governments at concessionary rates2, (iii) the International Finance Corporation (IFC) which finances private investments, (iv) the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) which provides guarantees to Governments and (v) the International Centre for Settlement of International Disputes (ICSID) which facilitates the settlement of investment disputes between governments and foreign investors. Currently, the World Bank3 has 184 member countries and assists its client countries (about 100 countries with nearly 5 billion inhabitants) in reducing poverty4 and supporting environmentally and socially sustainable development5. The basic focus of World Bank assistance to any given country is determined by a ‘country assistance strategy’, which describes the priority activities and reforms that form the mutuallyagreed programme in the country that will be supported by the Bank, in order to reduce poverty in a sustainable manner. This priority setting is supported by country-specific analytical work as well as by a dozen Bank-wide sectoral strategies, including the Bank’s Environment Strategy, approved by the Board of Directors in July 2001 (World Bank, 1999c). A specialized annex of the Environment Strategy provides details on the importance of SEA for policy, plan and programme analysis (Kjoerven, 1996). Lending by IDA and IBRD over the last three years has averaged a total of about US$20 billion per annum. Since 2003-04 approximately two-thirds of this lending went to investment and the rest to macro-economic and sectoral adjustment. Environmental Assessment of Investment Projects History The Bank’s Articles of Agreement establish the legal mandate for its activities; operational policies define the “rules of the game” by which these activities are carried out. Broadly speaking, such rules may be based on specific instructions that have been codified by Senior Management and issued as Operational Manual statements for guidance to staff. In 1989, the World Bank produced an Operational Directive on Environmental Assessment (OD 4.00), which was converted in 1991 to OD 4.01. During most of the 1990s, Bank operations followed the environmental requirements of that Directive. In the late 1990s the Bank began to convert Operational Directives—which combined elements of policy, procedure, and guidance—into separate short statements of mandatory policy (Operational Policies—OPs), mandatory instructions for carrying out the policy (Bank Procedures—BPs), and advice on good practice. Experience and feedback with this and other related administrative requirements from both environmental and operational staff led to a series of consultative and review processes that 2 Countries eligible for IDA financing are those that had a per capita income of less than $875 in 2002 See http://www.worldbank.org for a general introduction to the World Bank, its mission and activities 4 See http://www.worldbank.org/poverty 5 See http://www.worldbank.org/sustainabledevelopment 3 culminated in the release of Operational Policy 4.01 in January 1999, which became effective in March 1999. The World Bank has accumulated a decade of experience in assessing the environmental impact of its investment projects. This report represents the third in a series of documents that review. The first review of the effectiveness of the Bank’s environmental assessment (EA) policies and procedures was carried out in 1992, three years after the advent of Operational Directive (OD) 4.00. The second review covered the period FY693–95, following the 1991 amendment. And the third (and to this day, last) EA review covered the period FY95-00 and was published in May of 20027. Intent and Content The purposes of the Bank's policy and procedures for environmental assessment (EA) are to ensure that development options under consideration are environmentally sound and sustainable8 and that any environmental consequences are recognized early and taken into account in project design. As concern has grown worldwide about environmental degradation and the threat it poses to human wellbeing and economic development, many industrial and developing nations, as well as donor agencies, have incorporated EA procedures into their decision-making. Bank EAs emphasize identifying environmental issues early in the project cycle, designing environmental improvements into projects, and avoiding, mitigating, or compensating for adverse impacts. By following the recommended EA procedures, the Bank as well as implementing agencies, designers, and borrowers are able to address environmental issues immediately thereby reducing subsequent requirements for project processing and avoiding costs and delays in implementation due to unanticipated problems. World Bank-funded9 projects that apply Environmental Assessment are initially screened as part of an internal process. The Bank classifies the proposed project into one of four categories, depending on the type, location, sensitivity, and scale of the project and the nature and magnitude of its potential environmental impacts. (a) Category A: A proposed project is classified as Category A if it is likely to have significant adverse environmental impacts that are sensitive, diverse, or unprecedented. These impacts may affect an area broader than the sites or facilities subject to physical works. World Bank’s fiscal year spans over the July 1st-June 30th period. FY06, for instance, covers July 1, 2005 to June 30th, 2006. 7 It can be downloaded at http://intranet.worldbank.org/WBSITE/INTRANET/UNITS/ESSDNETWORK/INTSAFEPOL/0,,contentM DK:20456110~pagePK:64168332~piPK:64168299~theSitePK:584402,00.html 8 Sustainability at the project level is a very difficult concept to define. The Bank’s Environmental Assessment Sourcebook has a long explanation of what sustainability at project level means in operational terms. It boils down to recommending that, for renewable resources, harvest rates should not exceed regeneration rates and, for non renewable resources, depletion should be at a rate equal to or less than the rate of development of renewable substitutes. More on the subject in the EA Sourcebook, accessible at http://www.worldbank.org/environmentalassessment 9 The Bank’s safeguard policies, including EA, apply to all projects which receive World Bank funding, as stand alone loans/credits or through co-financing. The policies also apply to all projects funded by Bankmanaged funds, notably Global Environmental Facility (GEF), Carbon Finance (CF) and a variety of other funding sources. 6 (b) Category B: A proposed project is classified as Category B if its potential adverse environmental impacts on human populations or environmentally important areas-including wetlands, forests, grasslands, and other natural habitats--are less adverse than those of Category A projects (c) Category C: A proposed project is classified as Category C if it is likely to have minimal or no adverse environmental impacts. (d) Category FI: A proposed project is classified as Category FI if it involves investment of Bank funds through a financial intermediary, Over the years, additional specific environmental issues (several stemming from the adoption of international conventions like the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity – 1992 – ) as well as social and legal issues created the need for additional operational policies and bank procedures which, along with Environmental Assessment, constitute the ten safeguard policies10 of the World Bank. The application of the EA policy and procedures in World Bank funded11 projects is the subject of many evaluations and assessments by groups internal to the Bank (see institutional context). Perhaps as importantly, external scrutiny on Bank’s application of its safeguard policies, including EA, is very high. Any policy conversion or update is the subject of intensive public consultation all around the world, a huge task, but with very robust results. Outcome of the EA process The issue of EA effectiveness has been the topic of the evaluations of the policy’s implementation record ever since Operational Directive 4.00 was published in 1989. Over the years, the approach of effectiveness of EA has gradually focused on two key aspects: Preparation and adoption by the borrower of an Environmental Management Plan (EMP), the operational section of the EA report, Increased local capacity to prepare, review, clear and monitor the application of EA. The EMP is an instrument that details (Error! Bookmark not defined.) the measures to be taken during the implementation and operation of a project to eliminate or offset adverse environmental impacts, or to reduce them to acceptable levels; and (Error! Bookmark not defined.) the actions needed to implement these measures. The EMP is 10 Natural Habitats (OP/BP 4.04), Pest Management (OP 4.09), Indigenous Peoples (OP/BP 4.10), Physical Cultural Resources (OP/BP 4.11), Involuntary Resettlement (OP/BP 4.12), Forests (OP/BP 4.36), Safety of Dams (OP/BP 4.37), International Waterways (OP/BP 7.50), Projects in Disputed Areas (OP/BP 7.60). 11 EA and the other safeguard policies also applies to investments financed by instruments managed by the World Bank, including Global Environment Facility (GEF) grants, Carbon Finance emissions reduction purchases, and a few others. For investment projects co-financed by the World Bank or one of the instruments above, EA and the safeguard policies apply (i) to all project components and (ii) to the other co-financiers, unless they apply stricter policies and procedures than World Bank’s. an integral part of Category A EAs (irrespective of other instruments used). EAs for Category B projects may also result in an EMP. Three consecutive EA reviews have looked into EA effectiveness. Although the latest EA Review is as old as 2001, anecdotal evidence shows that most of its findings and recommendations remain valid. Although Category A projects are being handled increasingly well, Category B projects often require closer attention. • Too many projects with serious impacts on the environment are mistakenly categorized as “B” rather than “A,” so that key elements such as analysis of alternatives and potential environmental impact on a wider area than the project site, public consultations, and supervision do not receive adequate attention. The categorization issue and the related question of the Bank’s incentive system and how it affects such decisions need to be addressed. Another theme repeated in many of the reviews is the importance of involvement by environmental specialists. Such involvement, both in the early stages of project design and later, during supervision, is seen by several of the reviews as a factor contributing toward greater success in meeting safeguard provisions. Yet the most recent QAG assessment revealed that even some Category A projects are not being overseen by environmental specialists. One of the barriers is clearly cost; the reviews suggest that greater reliance on local specialists and more local capacity building may be the best way to improve environmental supervision, including monitoring of environmental management plan implementation, given resource restraints. Consultation and disclosure issues were raised in several of the reviews, particularly in relation to projects located in China. Another persistent theme was the need to develop better tools to identify underlying and long-term environmental and social impacts of Bank activities. That is, staff need to become more skilled at looking beyond the immediate project area to see the broader implications of changes likely to occur—to the environment or to the people located nearby—as a result of planned activities. Despite these shortcomings, the sum of the assessments reviewed shows that the Bank has made tangible progress in many areas of EA/safeguard performance. Several of the reviews note that the more recent the project, the more likely it is to be in compliance with Bank safeguard policy. Findings of the most recent Quality Assessment review— no projects were rated unsatisfactory or environmental aspects and no Category A projects received ratings below “satisfactory”— demonstrate tangible progress. This is undoubtedly due, in good part, to the training and guidance efforts undertaken over the last five years. Two areas that have received considerable attention over the past few years, and show resulting improvement, are public disclosure of information and public consultations on the EA process. Chapter 4 takes a close look at progress in these two areas. Reviews of Bank progress on public consultations are encouraging. More than three-quarters of projects reviewed were holding consultations at the two stages when they are required, and the quality of the consultations was also improving steadily. Studies demonstrating the positive impact of consultations, among other factors, have apparently helped to convince Bank staff and clients of the value of bringing public opinion into the EA process at critical moments, disclosing project information in a timely and appropriate manner, and involving local citizens in monitoring and evaluation of environmental projects. A set of recommendations for improving public consultations—such as more training for Bank staff, improved record-keeping, and improving the country legal environment—should contribute toward ongoing positive results. In regard to disclosure and supervision, the Review found that while some projects demonstrate best practices, in other cases compliance is spotty. Systems have been put in place to improve the record on disclosure within the Bank, through the collection of information in the InfoShop and Public Information Centers in several countries. Two aspects of EA quality are analyzed. It begins by looking at efforts to make project legal documentation reflect the new safeguards by tightening contractual language and the terms of reference (TORs) for consultants working on EA. The Legal Department, having reviewed EArelated language in 50 projects, is developing a guide to help project staff craft more adequate contractual documents and thus avoid legal loopholes that have permitted noncompliance in the past. While some attention has been devoted to sharpening TORs, this is an area requiring greater awareness and consideration. The review also covers the critical area of capacity building—both within and outside the Bank and through projects specifically aimed at institutional development (ID) in client countries. ESSD, the Regions, and the World Bank Institute have undertaken diverse training initiatives, which undoubtedly have contributed to improvements noted throughout the report. A new, online Safeguards Training Course being developed and tested at the time of this writing should constitute a particularly useful tool for continuing these efforts, given that it addresses all safeguard concerns and can be used anywhere in the world. Finally, a 1999 review of 28 institution-building projects identified some key problems specific to client countries (such as the “newness” of environmental issues and the agencies handling them) and the Bank (time pressures, incentives). A common theme is that managing environmental issues frequently requires cross-sectoral approaches and coordination, which is not the way that most countries or the Bank are accustomed to operating The institutional context New challenges Environmental Assessment of Policy Reforms, Plans and Programs History While the rest of the world was discovering the benefits of Strategic Environmental Assessment, the World Bank looked back in the late 90’s at the experience with its borrowers’ preparation of Environmental Assessments of Plans and Programs. It became clear that Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA) had indeed already used in operations financed by the World Bank. In July 2001, when the World Bank adopted its first environmental strategy Intent and Content Outcome of the EA process The institutional context New challenges A focus on Transboundary Environmental Assessments Origin and nature of TEA Case studies Lessons learned Conclusion