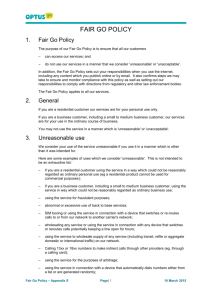

Cable & Wireless Optus

advertisement