INTRODUCTION - University of Washington

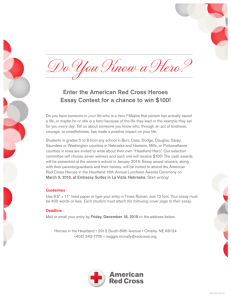

advertisement