The Marijuana Smokers

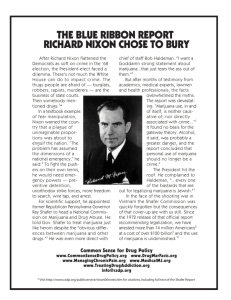

advertisement