Read the full report - University of Puget Sound

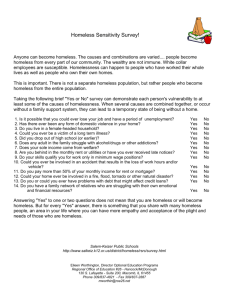

advertisement