Monopoly

advertisement

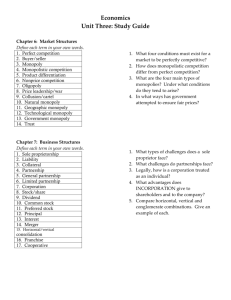

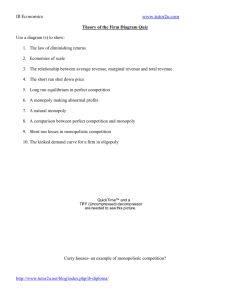

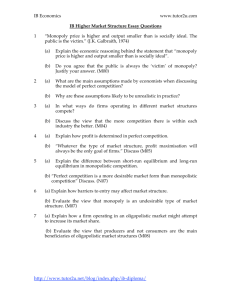

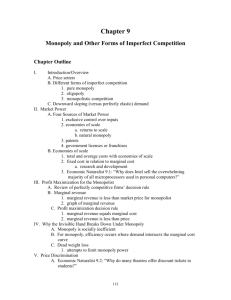

Chapter Monopoly CHAPTER OUTLINE 14 I. Explain how monopoly arises and distinguish between single-price monopoly and price-discriminating monopoly. A. How Monopoly Arises 1. No Close Substitutes 2. A Barrier to Entry a. Natural Barrier to Entry b. Ownership Barrier to Entry c. Legal Barrier to Entry B. Monopoly Price-Setting Strategies 1. Single-Price 2. Price Discrimination 2. Explain how a single-price monopoly determines its output and price. A. Price and Marginal Revenue B. Marginal Revenue and Elasticity C. Output and Price Decision 3. Compare the performance of single-price monopoly with that of perfect competition. A. Output and Price B. Is Monopoly Efficient? C. Is Monopoly Fair? D. Rent Seeking 1. Buy a Monopoly 2. Create a Monopoly by Rent Seeking 3. Rent-Seeking Equilibrium 4. Explain how price discrimination increases profit. A. Price Discrimination and Consumer Surplus 1. Discriminating Among Groups of Buyers 2. Discriminating Among Units of a Good B. Profiting by Price Discriminating C. Perfect Price Discrimination D. Price Discrimination and Efficiency 352 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 5. Explain why monopoly can sometimes achieve a better allocation of resources than competition can. A. Benefits of Monopoly 1. Capturing Economies of Scale 2. Strengthening the Incentives to Innovate B. U.S. Patent Law What’s New in this Edition? Checkpoint 14.5 has been rewritten. The material on regulating natural monopolies has been eliminated. In its place is a longer discussion of how monopoly can benefit society by capturing economies of scale and strengthening the incentive to innovate. The checkpoint concludes with a brief discussion of U.S. patent law. Where We Are In this chapter, we examine another market structure: monopoly. We discuss how monopoly arises and how a monopoly (single-price or price-discriminating) chooses its profit-maximizing output and price. Recognizing that monopoly creates a deadweight loss, we discuss whether monopoly is efficient and fair. The concept of rent seeking is examined and reveals that rent seeking is likely to extract all of the economic profit earned by a monopoly. Finally, benefits of monopoly is covered. Where We’ve Been The previous chapter studied perfectly competitive firms’ demand and marginal revenue curves. We combined them with the cost curve analysis in Chapter 12 to determine perfectly competitive firms’ profit-maximizing output and price decisions. Where We’re Going After this chapter we examine two more market structures: monopolistic competition, in Chapter 15, and oligopoly, in Chapter 16. Then, in Chapter 17, we move to a discussion of antitrust and regulation. All these chapters depend on the material presented in this chapter. Chapter 14 . Monopoly IN THE CLASSROOM Class Time Needed Because the students are familiar with firm behavior in perfect competition, this chapter is somewhat easier to present. You should spend between two to three class sessions on this material. An estimate of the time per checkpoint is: 14.1 Monopoly and How It Arises—15 minutes 14.2 Single-Price Monopoly—25 to 45 minutes 14.3 Monopoly and Competition Compared—30 to 40 minutes 14.4 Price Discrimination—30 to 40 minutes 14.5 Monopoly Policy Issues—10 to 15 minutes 353 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 354 CHAPTER LECTURE 14.1 How Monopoly Arises A monopoly has two key features: No Close Substitutes: There are no close substitutes for the good or service. Barriers to Entry: Legal or natural constraints that protect a firm from potential competition are called barriers to entry. Monopolies are protected by barriers to entry. Natural barriers to entry create a natural monopoly, which is an industry in which one firm can supply the entire market at a lower price than two or more firms can. When one firm owns all (or most) of a natural resource, it creates an ownership barrier to entry. DeBeers owns about 80 percent of the world’s diamonds. Legal barriers to entry create a legal monopoly, which is a market in which competition and entry are restricted by the granting of a public franchise (an exclusive right is granted to a firm to supply a good or service—the U.S. Postal Service has a public franchise to deliver first-class mail), a government license (when the government controls entry into particular occupations, professions and industries—a license is required to practice law), a patent (an exclusive right granted to the inventor of a product or service) or a copyright (exclusive right granted to the author or composer of a literary, musical, dramatic, or artistic work). There are many examples of government licensing. Licensing can protect consumers from fraud and abuse, but they can also hurt consumers by preventing competition from producing an efficient allocation of resources. Have the students debate the merits of the following licensing arrangements: 1) Doctors can receive a medical license to practice medicine only by graduating from an AMA approved medical program; 2) Lawyers can practice law only after passing an extensive Bar Exam; 3) Cab drivers in New York City can operate a taxi only if they have purchased a medallion from the city, of which there are a finite number; 4) Beauticians in many states cannot operate a beauty parlor without a state certification that requires training in sanitary practices as well as other courses completely unrelated to their profession (such as civics and history courses). Monopoly Price-Setting Strategies Price discrimination is the practice of selling different units of a good or service for different prices. Many firms price discriminate, but not all of them are monopoly firms. A single-price monopoly is a firm that must sell each unit of its output for the same price to all its customers. Chapter 14 . Monopoly 14.2 355 A Single-Price Monopoly’s Output and Price Decisions Price and Marginal Revenue The demand curve facing a monopoQuantity Total revMarginal ly firm is the market demand curve. Price demanded enue revenue Total revenue (TR) is the price (P ) $4 0 $0 multiplied by the quantity sold (Q ). $3 Marginal revenue (MR ) is the $3 2 $6 change in total revenue resulting $1 from a one-unit increase in the quan$2 4 $8 tity sold. The table shows the calcula$1 tion of TR and MR. $1 6 $6 A key feature of a single-price monopoly is that MR < P at each quantity so, as illustrated in the figure below, the MR curve lies below the demand curve. MR < P because a single–price monopoly must lower its price on all units sold to sell an additional unit of output. Marginal Revenue and Elasticity If demand is elastic, the MR is positive; if demand is unit elastic, the MR equals zero; and if demand is inelastic, MR is negative. A single-price monopoly never produces in the inelastic part of its demand because if it did, the firm could increase its total profit by decreasing its output, which would raise its total revenue and decrease its total cost. Output and Price Decisions To maximize its profit, a monopoly produces the level of output where MR = MC. The monopoly then uses its demand curve to set the price at the maximum possible price for which it will be able to sell the quantity it produces. In the figure, which uses the demand and MR schedules from the table above, the firm produces 200 units of output and sets a price of $160 per unit. The firm earns an economic profit if P> ATC, which is the case for the firm in the figure. The monopoly can earn the economic profit even in the long run because the barriers to entry protect the firm from competition. However, a monopoly firm is not guaranteed an economic profit. In the short run and/or long run, it might earn a normal profit, (P = ATC ) or in the short run, it might incur an economic loss (P > ATC ). Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 356 14.3 Single-Price Monopoly and Competition Compared Output and Price Perfect Competition: The market demand curve (D) in perfect competition is the same demand curve that the firm faces in monopoly. The market supply curve (S ) in perfect competition is the horizontal sum of the individual firm’s marginal cost curves. This supply curve also is the monopoly’s marginal cost curve, so in the figure above the supply curve is labeled MC. In a competitive market, equilibrium occurs where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied, which in the figure above is 250 units of output and a price of $140 per unit. Monopoly: The monopoly produces where MR = MC and sets its price using its demand curve. In the figure, the monopoly produces 200 units of output and sets a price of $160 per unit. Compared to a perfectly competitive industry, a single-price monopoly produces less output and sets a higher price. Is Monopoly Efficient? A perfectly competitive industry produces the efficient quantity of output. Because a single-price monopoly produces less output, it creates a deadweight loss. Though the monopoly creates a deadweight loss, the monopoly benefits its owners because it earns an economic profit. A monopoly benefits the owner because it redistributes some of the consumer surplus away from the consumer and to the monopoly producer. It is important for students to recognize that the source of the inefficiency of a monopoly firm’s output and pricing decision arises from the absence of competition in the market, rather than any change in the behavioral assumptions about the firm owners. So, “Mom and Pop,” the owners of a perfectly competitive firm, are maximizing their profit as surely as the owners of a monopoly. Rent Seeking The social cost of monopoly might exceed the deadweight loss it creates because of rent seeking, which is any attempt to capture consumer surplus, producer surplus, or economic profit. Rent seeking can occur when someone uses resources seeking the opportunity to buy a monopoly for a price less than the monopoly’s economic profit. Rent seeking also can occur when someone uses resources lobbying the government to restrict the competition faced by the lobbyist. The resources used up in rent seeking are a cost to society that adds to the monopoly’s deadweight loss. Because there are no barriers to entry in the activity of rent seeking, the resources used up can equal the monopoly’s potential economic profit. Chapter 14 . Monopoly 14.4 357 Price Discrimination Price discrimination is the practice of selling different units of a good or service for different prices. Price discrimination converts consumer surplus into economic profit. To be able to price discriminate, a firm must: Identify and separate different buyer types. Sell a product that cannot be resold Price Discrimination and Consumer Surplus Price discrimination occurs because of different willingnesses to pay for the good. A firm can charge the same buyer different prices for different units of a good or a firm can charge different prices to different groups of buyers. Discriminating Among Groups of Buyers: A firm can charge different customers different prices for the product. Groups with a higher average willingness to pay are charged a higher price and groups with a lower average willingness to pay are charged a lower price. An example is airline travel, where business travelers who have a high average willingness to pay and often make last-minute reservations are charged a higher price than leisure travelers, who have a low average willingness to pay and often make advance reservations. Discriminating Among Units of a Good: A firm can charge a higher price for the first units purchased and a lower price for later units purchased. An example is pizza delivery, where the second pizza is generally cheaper than the first. Perfect price discrimination occurs if a firm is able to sell each unit of output for the highest price anyone is willing to pay for it. In this case, the price of each unit is the same as the unit’s marginal revenue, so the firm’s (downward sloping) demand curve becomes the same as its marginal revenue curve. Output increases to the point where the demand (= marginal revenue) curve intersects the marginal cost and the efficient quantity is produced. The deadweight loss is eliminated. The firm’s economic profit is the greatest possible. But consumer surplus equals zero because the firm captures the entire consumer surplus. 14.5 Monopoly Policy Issues Benefits from Monopoly Economies of Scale: If a monopoly has economies of scale (so its ATC decreases as its output increases), it might be able to produce at lower cost than could several competing firms. Incentives for Innovation: Granting the discoverer a monopoly to an innovation increases the incentives to innovate. Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 358 Patents give the innovator a monopoly on the invention for 20 years. So patents strengthen the incentive to innovate but at the cost of granting a monopoly with the resulting deadweight loss. Consider the struggle for developing countries with populations dealing with world-wide epidemics such as AIDS. In the developed countries in which they operate, pharmaceutical companies are granted legal barriers (patents) on their drugs, granting them a legal monopoly and enabling them to earn a high economic profit once they bring a new and successful medicine to market. The anticipation of this profit provides the incentive for these firms to undertake the expensive (currently estimated at approximately $900 million per approved drug) and risky development of innovative cures for the terrible diseases afflicting mankind, such as AIDS. However, once the new medicines are made available, the absence of competition means the price is high, which decreases the use of these new medicines, especially among the population of the poorer, developing nations that have been hit the hardest by these diseases. So, once the drug is discovered, the monopoly creates a deadweight loss but without the economic profit the monopoly brings, the drug might not have been discovered. There is a tradeoff between current sufferers, who want a low price, and sufferers in the future, who want new and better medicines developed. Chapter 14 . Monopoly Lecture Launchers 1. Students love monopoly! Most of your students are taking an economics course because they think it will help them either get a better job or run a better business. Many of your students are aspiring entrepreneurs. You’ve just had them slog through a heavy chapter on perfect competition the bottom line of which is the bottom line is miserable. Normal profit might be the best that many people can achieve but it is not very exciting. This chapter teaches the students how to make a serious entrepreneurial income. Innovate, create a monopoly that produces something that people value much more than the cost of producing it, and price discriminate as much as possible. 2. After defining a monopoly, you can ask your students to discuss the economic factors which lead to the development of monopolies. To what extent are those conditions products of the free market? In which case, students can debate the role of government with regard to monopoly. If it is the result of natural coalescence in a free market, then is it equitable and/or efficient to intervene? Clearly there is no definitively correct answer to these questions, which is perhaps why they are so much fun to debate! 3. Explain that the monopoly model is a benchmark model. Similar to the case of perfect competition, although no real-world industry satisfies the full definition of a monopoly market, the behavior of firms in many real world industries can be predicted by using the monopoly model. Mention that this chapter examines the least competitive end of the spectrum of markets, just like Chapter 13 discussed the most competitive end. 4. Figure 14.5, the classic monopoly diagram, provides a good opportunity to tell your students about the contribution of one of the most brilliant economists of the 20th century, Joan Robinson. This diagram first appeared in her book The Economics of Imperfect Competition, published in 1933 when she was just 30 years old. You and your students can learn more about Joan Robinson at http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/profiles/robinson.htm . Women are still not attracted to economics on the scale that they’re attracted to most other disciplines. So the opportunity to talk about an outstanding female economist shouldn’t be lost. Joan Robinson was a formidable debater and reveled in verbal battles, a notable one of which was with Paul Samuelson on one of her visits to MIT. Anxious to make and illustrate a point, Samuelson asked Robinson for the chalk. Monopolizing the chalk and the blackboard, the unyielding Robinson snapped, “Say it in words young man.” Samuelson meekly obeyed. This story illustrates Joan Robinson’s approach to economics: work out the answers to economic problems using the ap- 359 360 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE propriate techniques of math and logic, but then “say it in words.” Don’t be satisfied with formal argument if you don’t understand it. Your students will benefit from this story if you can work it into your class time. Land Mines 1. Marginal revenue can be a sticking point for many students. Students find it easier to see the difference between the monopoly’s demand and marginal revenue curves if you take two steps. First develop a total revenue schedule using price and quantity data. Then add another column showing marginal revenue. As the text shows, place the marginal revenue values between the quantity values. In the next step, draw the demand and marginal revenue curves. Again, emphasize that marginal revenue is plotted between two quantity levels. By explicitly graphing the data, you also have the framework for showing that the price of the good is always less than marginal revenue of a monopoly. 2. Students differ in their learning styles. It is always wise to accommodate as many of these styles as possible. To more clearly show the deadweight loss, start with a numeric approach. Draw a figure, labeling points on the axes with prices and quantities. Use these values to make your point and explicitly calculate the deadweight loss. Then, realizing that some students learn better from a geometric approach, shade the appropriate areas. Chapter 14 . Monopoly 361 ANSWERS TO CHECKPOINT EXERCISES CHECKPOINT 14.1 Monopoly and How It Arises 1a. A large shopping mall in downtown Houston is not a monopoly because there are many other similar stores and malls nearby. 1b. Tiffany is not a monopoly because there are many other upscale jewelers. 1c. Wal-Mart is not a monopoly because there are many other similar retailers. 1d. The Grand Canyon mule train is a monopoly because there is only one firm providing mule-ride services in the Grand Canyon. 1e. The only shoe-shine stand licensed to operate in an airport is a monopoly. 1f. The U.S. Postal Service is a monopoly when it comes to first class mail. 2. The mule train is a natural monopoly because if two or more firms tried to produce mule train services, the costs would be higher because of congestion on the paths. The shoe-shine stand and U.S. Postal Service are legal monopolies. The shoe-shine stand can price discriminate because the service cannot be resold. The mule train ride and services of the U.S. Postal service can be resold, so they cannot price discriminate. CHECKPOINT 14.2 Single-Price Monopoly 1a. The table showing Fossett’s total revenue schedule and marginal revenue schedule is to the right. Price (thousands of dollars per ride) Total Marginal revenue revenue Quantity (thousands (thousands of (rides per of dollars dollars per month) per month) ride) 220 0 0 200 1 200 180 2 360 160 3 480 140 4 560 120 5 600 200 160 120 80 40 362 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 1b. Figure 14.1 illustrates Fossett’s demand curve and marginal revenue curve. 1c. Fossett’s marginal cost equals marginal revenue at 2 1/2 rides a month, where both equal $120,000. From the demand curve, the price is $170,000 a ride. The total cost of 2 1/2 rides a month is $320,000. Fossett’s total revenue equals the number of rides multiplied by the price per ride, which is (2 1/2 rides per month) ($170,000) = $425,000. So his total economic profit is total revenue minus total cost, which is $425,000 $320,000 = $105,000. 1d. As a result of the tax, Fossett’s fixed cost changes, but his marginal cost does not. His profit-maximizing level of output is still 2 1/2 rides a month and his price still equals $170,000. The tax decreases his economic profit by $60,000 so his new economic profit is $45,000. 1e. A $30,000 per ride tax increases Fossett’s marginal cost by $30,000 at every level of output. With the increase in his marginal costs, Fossett now sells 2 rides a month because this is the level at which his new marginal cost equals his marginal revenue (both equal $140,000). From the demand curve, Fossett sets a price of $180,000 a ride. Total profit equals total revenue minus total cost. His total revenue is 2 rides $180,000, which is $360,000. His total cost is $260,000 plus the tax of $60,000, which is $320,000. So his new economic profit is $360,000 $320,000 = $40,000. CHECKPOINT 14.3 Monopoly and Competition Compared 1. Bobbie’s barbershop is not efficient because she produces fewer haircuts than a perfectly competitive market would produce. The barbershop generates a deadweight loss of $3. The monopoly captures $6 of the consumer surplus. A rent seeker would be willing to pay $12, the amount of the economic profit. CHECKPOINT 14.4 Price Discrimination 1. For a firm to price discriminate it must be able to identify specific consumers’ willingness to pay different prices and must be able to prevent the resale of the good or service. So if a firm can identify customers’ willingness to pay different prices and if the firm can prevent resale of its good or service, then the firm can price discriminate. 2a. The diner is price discriminating. Chapter 14 . Monopoly 2b. The airline is price discriminating. 2c. The airline is price discriminating. 2d. The supermarket is price discriminating. 2e. Different interest rates reflect borrowers’ different risks, which is a possible cost. Charging different interest rates is not price discriminating. 2f. The water company is price discriminating. 2g. The cell phone company is price discriminating. 2h. The museum is price discriminating. 2i. If the price difference is based on different costs of generating electricity at different times of the day, then there is no price discrimination. CHECKPOINT 14.5 Monopoly Policy Issues 1a. The distribution of water is a natural monopoly because one firm can distribute water at a lower average total cost than could two or more firms. There are large economies of scale in water distribution because the cost of installing the water mains that must go down each street is high while the (marginal) cost of supplying another customer off of a main is quite low. As a result, as more customers are served, the average total cost decreases. 1b. Because water distribution is a natural monopoly, it cannot be supplied more efficiently by having competitive water companies. If there were several competitive water companies, each company’s average total cost would be higher than if there was only one company and so the total cost of supplying water with many companies would be higher than supplying it with only one company. 363 364 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE ANSWERS TO CHAPTER CHECKPOINT EXERCISES 1. The three types of barrier to entry are natural barriers to entry, ownership barrier to entry, and legal barriers to entry. A natural barrier to entry exists when one firm can meet the entire market demand at a lower price than two or more firms could. An ownership barrier to entry exists when one firm owns a natural resource that is necessary in order to produce the good or service. A legal barrier to entry exists when the government grants a public franchise, government license, patent, or copyright to a single firm. Local telephone service is a market with a natural barrier to entry. DeBeers, which owns more than 80 percent of the world’s raw diamonds, has an ownership barrier to entry. The pharmaceutical drug market has legal barriers to entry. Natural barriers to entry cannot be removed because they are the result of the existing technology. Ownership and legal barriers to entry are difficult to remove because the holder of the barrier will lobby intensively to protect its barrier. 2a. Technological change has made personal computers more affordable and has created a monopoly for Microsoft in the production of operating systems for PCs. Technological change has resulted in many new pharmaceutical drugs being developed and so has created a monopoly for the firms developing specific drugs. Technological change has created the Internet and has given MCI a virtual monopoly over “backbone” services for the Internet in many areas. 2b. Technological change has made it possible for many more firms to provide phone service, both local and long distance. Technological change has allowed home television dish systems to compete with cable television. Technological change has decreased the efficient size of electrical generating plants and has allowed more firms to enter the market to generate electricity. 3. The good or service produced by a monopoly has no close substitutes, so its demand is not perfectly elastic. In this case, when the monopoly raises the price of its good or service, people continue to buy some of it because they have nothing else that (perfectly) takes its place. The good or service produced by a perfectly competitive firm is identical to the good or service produced by its competitors, so its demand is perfectly elastic. If a perfectly competitive firm raises the price of its good or service, people buy none of it because there are perfect substitutes available. 4. Price discrimination occurs when a monopoly is able to sell different units of a good or service for different prices. In some instances, different consumers pay a different price for the good or service. In other instances, the same consumer pays a different price for different units of the good or ser- Chapter 14 . Monopoly 365 vice. Not all monopolies can price discrimination. In order to price discriminate, a monopoly must be able to identify which buyers have a higher willingness to pay and to be able to prevent resale of the good by the customers who buy for the lower price. 5. A monopoly’s marginal revenue curve is downward sloping because a monopoly faces a downward sloping (market) demand curve. As a result of the demand curve, in order for a monopoly to sell an additional unit of output the monopoly must lower its price. So when a monopoly sells an additional unit, there are two effects on its total revenue: First, the firm collects the new, lower price on the additional unit sold. Second, the firm loses the difference between the old, higher price and the new, lower price on all the units it had previously sold. As more units are sold, the new price decreases and the amount lost on all the previous units sold increases. On both counts, the marginal revenue decreases as the quantity produced and sold increases. 6a. Elixer Spring’s total revenue and marginal revenue schedules are in the table to the right. Figure 14.2 illustrates Elixer’s total revenue curve and Figure 14.3 illustrates Elixer’s marginal revenue curve and its demand curve. Total Marginal Price Quantity revenue revenue (dollars per (bottles per (dollars (dollars per bottle) day) per day) bottle) 10 0 0 9 1,000 9,000 8 2,000 16,000 7 3,000 21,000 6 4,000 24,000 5 5,000 25,000 4 6,000 24,000 3 7,000 21,000 2 8,000 16,000 1 9,000 9,000 0 10,000 0 9 7 5 3 1 1 3 5 7 9 366 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 6b. In Figure 14.4, the marginal cost curve runs along the horizontal axis because the marginal cost is zero. Elixir produces where the marginal cost curve intersects the marginal revenue curve, so the figure shows that Elixir produces 5,000 bottles a day. Elixir sets a price of $5 a bottle because that is the price at which 5,000 bottles a day is the quantity demanded. Elixir’s profit equals its revenue, which is $5 a bottle 5,000, = $25,000 a day, minus its cost, which is its fixed cost of $5,000 a day. So Elixir’s economic profit is $25,000 $5,000, which is $20,000 a day. 6c. The price, $5, is well above the marginal cost, $0. 6d. As Figure 14.2 shows, Elixir is producing where its total revenue is at its maximum. So the elasticity of demand for Elixir water equals 1.0. Chapter 14 . Monopoly 7a. Blue Rose’s total revenue and marginal revenue schedules are in the table to the right. Figure 14.5 illustrates Blue Rose’s total revenue curve and Figure 14.6 illustrates Blue Rose’s marginal revenue curve and also its demand curve. 367 Total Marginal revenue revenue (dollars (dollars per per day) bunch) Price (dollars per bunch) Quantity (bunches per day) 80 0 0 72 1 72 64 2 128 56 3 168 48 4 192 40 5 200 32 6 192 24 7 168 16 8 128 72 56 40 24 8 8 24 40 368 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 7b. The marginal cost schedule is in the table to the right. The marginal cost curve is illustrated in Figure 14.6 (on the previous page) as MC. 7c. To maximize profit, Blue Rose produces where the marginal cost curve intersects the marginal revenue curve. Figure 14.6 shows that Blue Rose produces 3 1/2 bunches a day. The demand schedule shows that the price is $52 a bunch because that is the price at which 3 1/2 bunches per day is the quantity demanded. The total revenue when 3 1/2 bunches a day are produced is 3 1/2 bunches $52 a bunch, which is $182 a day. Blue Rose’s cost schedule shows that the total cost of producing 3 1/2 bunches a day is $112. So Blue Rose’s total economic profit is its total revenue minus its total cost, which is $182 dollars a day $112 a day = $70 a day. Quantity (bunches per day) Total Marginal cost cost (dollars (dollars per per day) bunch) 0 80 1 82 2 88 3 100 4 124 5 160 6 208 7 268 8 340 8a. If there are 1,000 firms, the market is perfectly competitive. The price equals the marginal cost, so the price is zero. At a price of zero, the quantity demanded is 10,000 bottles a day. 8b. The monopoly price, $5 a bottle, is higher than the perfectly competitive price of zero. The monopoly quantity, 5,000 bottles a day, is less than the perfectly competitive quantity of 10,000 bottles a day. 8c. The consumer surplus is the triangular area under the demand curve and above the price. The area of a triangle equals 1/2 base height, so the consumer surplus equals 1/2 10,000 bottles a day $10 a bottle, which is $50,000 a day. 8d. Producer surplus equals the area above the supply curve and below the price. If the water is produced in perfect competition, the price is zero, so the producer surplus for Elixir water is zero. 8e. If a monopoly produces Elixir water, consumer surplus equals 1/2 5,000 bottles a day $5 a bottle, which is $12,500 a day. Producer surplus equals the area above the marginal cost curve and below the price. In the case of a monopoly producer of Elixir water, this area is a rectangle and equals $5 a bottle 5,000 bottles a day, which is $25,000 a day. 8f. The deadweight loss equals the total surplus (the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus) when the market is perfectly competitive minus the total surplus when the market is a monopoly. The total surplus when the market is perfectly competitive is $50,000 a day. The total surplus when the market is a monopoly is $37,500 a day. The deadweight loss equals $50,000 a day minus $37,500 a day, which is $12,500 a day. 2 6 12 24 36 48 60 72 Chapter 14 . Monopoly 369 9a. The most a firm is willing to pay to obtain a monopoly is the amount of economic profit. If there are no fixed costs, then the total economic profit when one firm produces Elixir water is $25,000 a day. So the most a firm is willing to pay is $25,000 a day. 9b. When Elixir water is produced by a monopoly, the price is $5 a bottle and the quantity is 5,000 bottles a day. Figure 14.7 illustrates the economic profit when Elixir water is produced by a monopoly. The economic profit is the shaded rectangular area. 9c. If the firm pays $25,000 a day to secure the monopoly, the firm has an additional cost of $25,000 a day. With this cost it is not earning any economic profit. Rent seeking has eliminated the economic profit. Total Marginal Marginal 10a. Bobbie produces revenue revenue Total cost the quantity such Price Quantity (dollars (dollars cost (dollars that marginal (dollars per (haircuts per per hair- (dollars per hairrevenue equals haircut) per hour) hour) cut) per hour) cut) marginal cost. 20 0 0 20 The table to the 18 1 right has Bob18 1 18 21 14 3 bie’s marginal 16 2 32 24 revenue and 10 6 14 3 42 30 marginal cost 6 10 schedules. The 12 4 48 40 2 15 table shows that 10 5 50 55 Bobbie produces 3 haircuts an hour at a price of $14 a haircut. Her economic profit is her total revenue, $42, minus her total cost, $30, which is $12. 10b. If Bobbie price discriminates, she charges the woman $18, the senior citizen $16, the student $14, and the boy $12. 10c. If Bobbie price discriminates, she sells 4 haircuts an hour. 370 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 10d. Bobbie’s economic profit is her total revenue minus her total cost. Her total revenue is $18 + $16 +$14 + $12, which is $60. Her total cost to produce 4 haircuts is $40, so her economic profit is $60 $40, which is $20. 10e. Because Bobbie is perfectly price discriminating, Bobbie is producing the efficient quantity of haircuts. 10f. Because Bobbie is charging each customer the maximum the customer is willing to pay, there is no consumer surplus. Consumer surplus is zero. Bobbie’s producer surplus is $33.50. The producer surplus on the first hair cut is $18 - $2 = 16, where the $2 is the marginal cost. The producer surpluses on the remainder of the haircuts are calculated similarly. 10g. Bobbie benefits because her economic profit is higher. The boy willing to pay $12 benefits because he now gets a haircut. Society benefits because the deadweight loss is eliminated. 11. The museum can offer discounts to senior citizens and students. It could offer free admission to children accompanied by adults to attract more visitors. Total Marginal 12a. Big Top’s total revenue and Price Quantity revenue revenue marginal revenue schedules (dollars per (tickets per (dollars (dollars per ticket) show) per show) show) are in the table to the right. 12b. Big Top’s marginal cost is con20 0 0 stant and equal to $6 per tick18 18 100 1800 et. So Big Top’s marginal rev14 enue equals its marginal cost 16 200 3200 10 when the quantity of tickets is 14 300 4200 350 tickets per show and the 6 12 400 4800 price is $13 per ticket. The total 2 revenue is 350 tickets $13, 10 500 5000 2 which is $4,550. The total cost 8 600 4800 of 350 tickets is $3,100. So the 6 6 700 4200 economic profit equals $4,550 10 $3,100, which is $1, 450. 4 800 3200 12c. The consumer surplus equals 1/2 ($20 $13) 350, which is $1,225. The producer surplus is the area above the marginal cost curve and below the price. Because the marginal cost curve is horizontal, this area is a rectangle equal to ($13 $6) 350, which is $2,450. 12d. When Big Top maximizes its profit, the circus is not efficient. At 360 tickets, the marginal cost of another ticket is $6 and the marginal benefit from another ticket (which is equal to the maximum a consumer is willing to pay) is $13. Marginal benefit is greater than marginal cost, so a deadweight loss exists. Chapter 14 . Monopoly 12e. If the industry was perfectly competitive, 700 tickets would be sold at a price of $6 per ticket. 12f. If Big Top offers a child discount, the consumer surplus decreases and the producer surplus increases. Big Top sells more tickets and so it operates closer to the efficient level of output. 371 372 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE Critical Thinking 13a. The NCAA is a legal monopoly. It effectively has purchased 100 percent of the market for college athletics. If another group tries to sanction a college sport, the NCAA would expel from all sports any college that joined the competing group. 13b. The colleges gain because they are able to limit competition and make an economic profit. The coaches and other participates whose incomes are not set by the NCAA also gain because they can demand higher income from the profit the colleges earn. 13c. The system operated by the NCAA is not efficient. It restricts the amount of athletic competition to less than the efficient quantity. 14a. Competition can be introduced into the market for baseball by declaring it no longer exempt from the laws designed to limit market power. 14b. If competition is introduced, quite likely the number of teams would increase and each team’s economic profit would decrease. One factor that suggests otherwise is the point that fans enjoy baseball because it is a competition with an uncertain outcome. If large market teams (such as New York) totally dominated the sport, fans might lose interest, in which case the league would contract. 14c. If, on net, the league expanded, then the number of players would increase and likely their salaries would rise. If the lack of effective competition amongst teams decreased the size of the league, the number of players would decrease. 14d. The current situation is inefficient but a “level playing field” amongst teams is, to some extent, preserved. If the student thinks that making baseball less of a monopoly would not harm the competitive balance, then the student might favor removing monopoly power. However if the student believes that removing monopoly power would unduly harm the competitive balance amongst teams, then the student might favor allowing the league to retain its monopoly power. 15. Before 1991, the Ivy League colleges operated as a monopoly. They set the price of education equal to the monopoly price. Since 1991, the colleges have been competitors. The price of education has fallen from what it otherwise would have been. The efficiency of the market increased. Producer surplus decreased, consumer surplus increased, and deadweight loss decreased. Chapter 14 . Monopoly Web Exercises 16a. Robert Barro’s central argument is that to pay for innovation, firms need a period of time during which they have a monopoly in the newly innovated product. So, government intervention that lowers the price decreases the profit from innovation and slows innovation, which harms consumers. 16b. Your students might or might not agree with Barro’s argument. You might note that Barro’s argument is consistent with a free-market view that the government ought not to intervene in the economy. 16c. Barro’s argument suggests that government intervention to limit monopoly power should, itself, be limited. In particular, Barro’s argument strongly suggests that intervention in rapidly innovating sectors of the economy should be eliminated. 17a. Microsoft was found to be a monopoly: “…Microsoft enjoys monopoly power in the relevant market.” This finding is in the “Court's Findings of Fact (11/5/99)”, at: http://www.usdoj.gov/atr/cases/ms_findings.htm. 17b. To determine that Microsoft is a monopoly, the court defined the relevant market as computers powered by Intel compatible chips and then noted Microsoft’s huge market share in operating systems in this market. 17c. The court eventually said that Microsoft can not retaliate against a computer manufacturer who ships computers with non-Microsoft software, that Microsoft must allow computer manufacturers to create computers that open to a screen developed by the manufacturer, and that Microsoft must make available to other software makers information about how to work well with Windows. 17d. Robert Barro would suggest that the government take no action in the Microsoft case. However, given the relatively limited sanctions imposed on Microsoft, he likely would not disapprove too strongly of the ultimate result. 18. Although your students’ answers will depend on the information they gather, what they will find is that the trips with the most restrictions generally have the lowest prices. And the restrictions are generally designed to separate vacation or leisure travelers from business travelers. The airline’s goal is to charge the highest price a traveler is willing to pay and business travelers are almost always willing to pay higher prices than leisure travelers. 373 374 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE ADDITIONAL EXERCISES FOR ASSIGNMENT Questions CHECKPOINT 14.1 Monopoly and How It Arises 1. Which of the following situations is a monopoly? 1a. The supermarket that stocks the best-quality products 1b. The supermarket that charges the highest prices 1c. The firm that has the largest share of the market sales 1d. The truck stop in the Midwest, miles from anywhere 1e. A firm that produces a good that has a perfectly inelastic demand 1f. The only airline that flies from St. Louis to Kansas City 2. Which of the cases in Exercise 1 are natural monopolies and which are legal monopolies? Which can price discriminate, which cannot, and why? CHECKPOINT 14.2 Single-Price Monopoly 3. Dolly's Diamond is a single-price monopoly. The first two columns of the table show the demand schedule for Dolly's Diamond, and the middle and third column show the firm's total cost schedule. Price Quantity Total cost (dollars per (carats per (dollars per carat) day) day) 2,200 0 2,000 1 3a. Calculate Dolly's total revenue schedule and 1,800 2 marginal revenue schedule. 3b. Sketch Dolly's demand curve and marginal 1,600 3 revenue curve. 1,400 4 3c. Calculate Dolly's profit-maximizing output, 1,200 5 price, and economic profit. 3d. If the government places a fixed tax on Dolly's Diamond of $1,000 a day, what are Dolly's new profit-maximizing output, price, and economic profit? 3e. If instead of imposing a fixed tax on Dolly's, the government taxes diamonds at $600 a carat, what are Dolly's new profit-maximizing output, price, and economic profit? 800 1,600 2,600 3,800 5,200 6,800 Chapter 14 . Monopoly CHECKPOINT 14.3 Monopoly and Competition Compared 4. The figure shows an industry. If the market is perfectly competitive, what is the equilibrium quantity that will be produced and the equilibrium price? If the market is a single- price monopoly, darken in the area of the deadweight loss. CHECKPOINT 14.4 Price Discrimination 5. What is price discrimination? Give some real-world examples of price discrimination. 6. Which of the following situations is price discrimination? 6a. The local drug store offers senior citizens a discount on all purchases made on Tuesdays. 6b. Domino’s offers “Buy 1 pizza for $15 and get a second one for only $1.” 6c. Farmers in Southern California pay a lower price for water than do the residents of Los Angeles. 6d. The U.S. Postal Service charges a lower price to mail a postcard than to mail a letter. Answers CHECKPOINT 14.1 Monopoly and How It Arises 1a. The supermarket that stocks only the best-quality products is not a monopoly. The statement does not say that no other markets stock these products. If indeed it is the only supermarket in the area that stocks these high-quality products, it still is not a monopoly because there are no barriers to entry to prevent other supermarkets from also stocking the best-quality products. 1b. A supermarket that charges the highest prices is not a monopoly. 1c. The firm with the largest market share is not necessarily a monopoly. 1d. A truck stop miles from anywhere is a monopoly. 375 376 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 1e. A firm producing a good with perfectly inelastic demand could be a monopoly. Inelastic demand implies that there are no close substitutes for the good (like insulin), but does not imply that other firms are prevented from entering the market. Unless there is a barrier to entry, the firm is not a monopoly. But, more generally, simply because the demand for a product is inelastic does not mean that the producer is a monopoly. 1f. An airline with the only service on a route has monopoly power on that route. 2. Because the truck stop is in the middle of nowhere, the market demand for automobile and truck services is relatively small, so the truck stop is a natural monopoly. If two truck stops supplied the market, costs would be higher. (The truck stop could have a legal monopoly if it has purchased all surrounding land or if it lobbied the government to allow it to have the only building permit for the area.) The airline might be a legal monopoly if it has been awarded sole landing rights at one of the airports. The airline can price discriminate because the service cannot be resold. CHECKPOINT 14.2 Single-Price Monopoly 3a. The table showing Dolly’s total Total Marginal revenue and marginal revenue Price Quantity revenue revenue (dollars per (carats (dollars per (dollars per schedules is to the right. carat) per day) day) carat) 2,200 0 0 2,000 1 2,000 1,800 2 3,600 1,600 3 4,800 1,400 4 5,600 1,200 5 6,000 2,000 1,600 1,200 800 400 Chapter 14 . Monopoly 3b. Figure 14.9 illustrates Dolly’s demand and marginal cost curves. 3c. Dolly’s marginal cost equals marginal revenue at 2 1/2 carats a day, where both equal $1,200. From the demand curve, the price is $1,700. Total cost of 2 1/2 carats a day is $3,200. Dolly’s total revenue equals (2 1/2 carats) ($1,700) = $4,250. Her total economic profit is $4,250 $3,200 = $1,050. 3d. As a result of the tax, Dolly’s fixed cost changes, but her marginal cost does not. Her profitmaximizing level of output is still 2 1/2 carats and her price still equals $1,700. The tax eliminates all but $50 of Dolly’s economic profit. 3e. A $600 a carat tax increases Dolly’s marginal cost by $600 at every level of output. With the increase in her marginal costs, Dolly now sells 1 1/2 carats a day because at this quantity marginal cost equals marginal revenue, which is $1,600. From the demand curve, Dolly’s sets a price of $1,900 a carat. Her total profit equals her total revenue minus her total cost. Her total revenue is (1 1/2 carats) ($1,900) = $2,850. Her total cost is $2,100 plus the tax of $600, which is $2,700. Dolly’s economic profit is $2,850 $2,700 = $150. 4. CHECKPOINT 14.3 Monopoly and Competition Compared If the market is perfectly competitive, 2 units are produced and the price is $30. The darkened triangle in Figure 14.10 shows the deadweight loss if the market is a single-price monopoly. 377 378 Part 5 . PRICES, PROFITS, AND INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE CHECKPOINT 14.4 Price Discrimination 5. Price discrimination is a firm offering the same good for sale at different prices. Examples are a shoe store offering one pair of shoes for $50 and a second pair for half price. A restaurant that offers early bird specials for dinners before 6 pm or a movie theater that offers lower matinee ticket prices are engaging in price discrimination. 6a. The drug store is price discriminating. 6b. Domino’s is price discriminating. 6c. The residents might not face price discrimination. There could be higher costs to transport the water to Los Angeles. If the different prices are based on volume use or if the different prices are based on different types of users, then there is price discrimination. 6d. If the price difference is based on different costs of mailing a letter versus a postcard, then there is no price discrimination. Chapter 14 . Monopoly USING EYE ON THE U.S. ECONOMY Airline Price Discrimination The story provides a good example of how airlines identify many buyer types. Charging different prices alone does not guarantee price discrimination. Airlines effectively price discriminate by requiring passengers to show identification. Before security scares, passengers could board a plane without showing identification so airlines could not prevent the resale of tickets. At that time, price discrimination was more difficult. You might see tickets advertised in the newspapers. There were businesses devoted to reselling low-priced tickets! For example, at that time, you could buy your grandmother’s ticket for which she paid a reduced senior citizen fare. Today, even are valid security reasons for showing identification, so it is much easier for airlines to prevent resale of tickets. You can no longer resell tickets and so airlines can more easily and more effectively price discriminate. 379