NPC Project

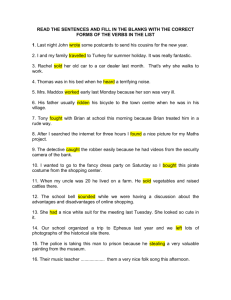

advertisement