Services - General

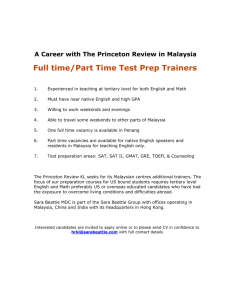

advertisement