IGP-5 - Global Environmental Change and Food Systems

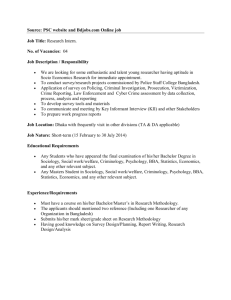

advertisement