Impacts - Department of Premier and Cabinet

advertisement

afford

affordable age areas believe cars charges cheap city closures community

cost

costs due education efficient electricity

every everyone expensive facing feel

get getting giving good

high

form free

fuel further

future gas

government health

home homeless house

include income installation issues

make may

food

enterprises entry ever

heating help here

of houses housing important

less

living low

just keep

money most

life like live

must my

need new night north of off oil old one

people poor population

power prices provide reduce safe school services solar think

transport use utilities volunteers water

outcome over

owned panels particularly pay

price

place

Cost of Living in

Tasmania

COMPANION REPORT 2 - IMPACTS AND RESPONSES

OCTOBER 2011

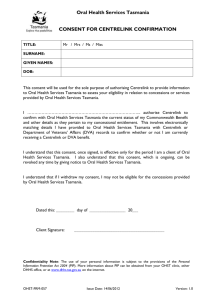

Cover image:

Over 5 000 Tasmanians participated in the community consultation process for the

Tasmania Together 10 Year Review, which was held between September and

December 2010. The cover image is a cloud tag, which documents the frequency of

words that were used in community responses on the theme of cost of living. The

larger the word in the cloud tag, the greater is the frequency of use of this word in

survey responses received.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 6

IMPACTS............................................................................................. 9

Households ............................................................................ 11

People ..................................................................................... 21

Places ...................................................................................... 30

RESPONSES .....................................................................................40

Increasing productivity ......................................................40

Building financial capability .............................................46

Strengthening consumer protection ............................ 55

Building networks of support .......................................... 60

Strengthening the safety net .......................................... 67

Appendices

Appendix 1 Flanagan, J and Flanagan, K, 2011 The price of poverty: cost of living

pressures and low income earners, Hobart: Anglicare Tasmania.

Appendix 2 Fudge, M. 2011 Local voices: enquiry into community assets in Circular

Head, Tasmania. Hobart: Relationships Australia Tasmania.

Appendix 3 Dare, M, Kimber, J and Schirmer, J, 2011 Tasmanian Drought Evaluation

Project, Hobart: University of Tasmania and JS Consulting.

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Community Inclusion Workers, Child and Family Centres Project 2011

Community consultation report for the Social Inclusion Unit,

Department of Premier and Cabinet.

Council on the Ageing Tasmania, 2011 A sense of belonging: social

inclusion issues for older people in Tasmania, Hobart: COTA Tas.

4

5

Introduction

This report examines the impacts of cost of living pressures on particular

households, population groups, and places. It provides additional detail to that

contained in A Cost of Living Strategy for Tasmania, regarding a selection of

responses to cost of living pressures facing Tasmanian communities.

Individuals and households can be more included or excluded from social and

economic participation depending on the level of cash and non-cash resources

available to help them manage costs and sustain a decent quality of life1. The

question of which groups are most affected by cost of living increases is determined

by the complex interplay of price increases, household expenditure and the

resources that households have available to absorb price increases.

There are a variety of methodologies available to determine the groups most

affected by cost of living increases and depending on the methodology a different

ordering of groups is likely to result. A Cost of Living Strategy for Tasmania uses the

Relative Price Index (RPI) as the principle methodology for determining groups most

likely to be impacted as this approach provides current Tasmanian specific data that

accounts for the differing expenditure patterns of household groups 2.

This report considers data and analysis from a variety of qualitative and quantitative

sources in relation to the vulnerability or resilience of various households, people

and places experiencing cost of living risk.

Cost of living risk is defined in A Cost of Living Strategy for Tasmania as risk of

electricity disconnection, housing eviction and homelessness, food insecurity, ill

health due to inability to afford health services, debt and financial pressures, and

presentations to emergency relief services. Factors that contribute to cost of living

The debate about adequate living standards generally occurs with reference to concepts such as ‘absolute

poverty’ and ‘relative poverty’. Absolute poverty refers to a minimum standard below which no one anywhere in

the world should ever fall and which is the same in all countries and does not change over time. Relative

poverty refers to a standard which is defined in terms of the society in which an individual lives and which

therefore differs between countries and over time – minimum standards can rise and fall if and as a country

becomes richer. http://www.poverty.org.uk/summary/social%20exclusion.shtml

Recent research on poverty in modern Australia (2006 and 2010) has found that the majority of Australians

consider the following items to be essential for a decent life – i.e. that no-one in Australia should have to go

without: warm clothes and bedding, if it’s cold; a substantial meal at least once a day; computer skills; a decent

and secure home; a roof and gutters that do not leak; secure locks on doors and windows; heating in at least

one room of the house; furniture in reasonable condition; a washing machine; a television; up to $500 in savings

for an emergency; home contents insurance; comprehensive motor vehicle insurance; regular social contact with

other people; a telephone; presents for family or friends each year; a week’s holiday away from home each year;

medical treatment if needed; able to buy prescribed medicines; dental treatment if needed; children can

participate in school activities and outings; an annual dental check-up for children; a hobby or leisure activity for

children; new schoolbooks and school clothes; a separate bed for each child; and a separate bedroom for

children aged 10 and over. See Saunders, P, and Wong, M, 2009 Still doing it tough: an update on deprivation

and social exclusion among welfare service clients, Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, p.10; and Saunders, P,

and Wong, M, 2011 Social impact of the Global Financial Crisis, Newsletter No. 108, Sydney: Social Policy

Research Centre, p.6.

2 See Companion Report 1 for further information about the Relative Price Index.

1

6

risk include income adequacy, the affordability of essential goods and services,

information about the products and prices available in the market, access to support

networks and emergency buffers to cope with price shocks, and individual skills and

capacity including physical and mental health.

Tasmanians are facing financial difficulty as a result of cumulative cost of living

impacts. As a consequence of financial difficulty, people adopt one or more ‘coping’

strategies such as:

Substitution;

Rationing;

Seeking increased resources through personal, family or community actions;

Falling into the social safety net; and/or

Simply going without the basics.

The Anglicare Report The price of Poverty (Appendix 1) provides a current picture of

the impacts of current cost of living pressures for low income households. It

identifies a number of ways in which low income Tasmanians are subject to an

additional cost in money, time or health which they incur in their attempts to

purchase basic goods and services (poverty penalty). It suggests that affordability of

essential services is approaching crisis point.

The Relationships Australia Report Local Voices (Appendix 2) identifies community

assets and strengths that support a regional community’s resilience and capacity to

recover and recreate in the face of economic challenges. It shows the importance of

strong social connections and relationships, formal and informal institutions and

infrastructure to support and foster participation, as well as the skills and capacities

of local people and their willingness to work together to support each other in

practical ways and with emotional support.

The Tasmanian Drought Evaluation Project (Appendix 3) highlights the interactive

nature of drought impacts and drought initiatives in farming communities, and how

it impacts people in different ways depending on their circumstances. It identifies

three key forms of support that families and communities need to survive the

negative impacts of drought (including cost of living impacts) – emotional and social

support, financial support and the support of farm production (their means to make

a living).

The Community Inclusion Workers’ Community Consultation Report (Appendix 4)

provides insights into how people in rural and urban communities are coping with

cost of living pressures, and how they think cost of living issues should be tackled.

While some people offered suggestions and good practice ideas, it reports that

many people have given up and are simply trying to survive – they are weary and

resigned to ever increasing costs and a bleak future.

The Council on the Ageing Tasmania (COTA Tas)’s report A Sense of Belonging

outlines the result of consultation with older Tasmanians about being connected to

7

community and key issues as they age. Although money and cost of living were not

raised as key issues, this report featured the cost of activities or being involved,

including telecommunications and cost of transport. Key issues were transport and

availability of information.

8

Impacts

The extent to which cost of living pressures become a significant issue for people

can depend on how quickly prices increase over time (pace of change) and by how

much (rate of change) relative to the income and resources of individuals and

households. Cost pressures can be exacerbated when people face an increase which

is more than expected, a number of bills hit at the same time and exceed the

capacity of regular household income and economic resources to respond, or

unexpected and unbudgeted expenses arise because of an emergency or

catastrophic event. The resilience and capacity of households, people and places to

cope with shocks is a key factor in the level of financial hardship they experience.

Faced with too many price shocks (i.e. the number of price rises and their amount)

people are finding it increasingly difficult to absorb these within the family budget.

It’s pretty tough ... for instance this month we had registration on the

vehicle which was $409; new muffler and service on the vehicle –

another $200 odd ... and we pay a pretty high rent of $170 a week.

So it doesn’t leave anything for any luxuries.

Age Pensioner Couple, North West Coast3

Got to constantly juggle bills just to get by.

Derwent Valley community consultation4

If I get one unexpected bill we will go under and cannot feed

ourselves.

Geeveston community consultation5

Recent research by the Commonwealth Bank has found that many Australians are

worried over pressure on household budgets, and a high proportion would struggle

to cope with an unexpected expense6. It found that 53% of respondents said they

would have difficulty finding $5 000 to fund an unplanned expense, with regional

respondents facing even greater challenges. It also found that 58% of women

compared to 48% of men said they would have difficulty raising $5 000 in an

emergency7.

Anglicare Tasmania recently asked low income Tasmanians about their expenditure

on essential services and products, and the decision making that drives their

budget8. It found that the most significant budget strategy employed by

TasCOSS, 2009 Just scraping by? Conversations with Tasmanians living on low incomes, p.15

Community Inclusion Workers, Child and Family Centres Project 2011 Community consultation report for the

Social Inclusion Unit, Department of Premier and Cabinet

5 Ibid

6 Commonwealth Bank & NATSEM, September 2010. Economic Vitality Report, Issue 2.

7 Ibid

8 Flanagan, J, and Flanagan K, 2011 The price of poverty: the cost of living for low income earners, Hobart:

Anglicare Tasmania.

3

4

9

households is to prioritise the payment of rent or mortgage costs, followed by

electricity and telecommunications9. This entails trade-offs that include food

rationing, compromises on electricity consumption, withdrawal from social

participation, and the use of credit to pay for essential purchases. Juggling bills and

using the money made available through delaying payment of bills is also an

important financial management strategy. Some research participants, for example,

reported that they delayed bill payments to purchase food and a cycle of small

loans from family members. If unable to reduce their electricity usage but also

unable to afford the cost of what they use, age pensioners cut back on their food

intake, while families accrue arrears and use emergency relief as a coping strategy

Yeah I get what I need first because if I got food first I would go

overboard, and then I wouldn’t have money for what I need. So I get

what I need and then I can see if I need extra loaves of bread.

21 year old part-time carer and student (New Start Allowance)10

External shocks on a household can include emergency events such as the

breakdown of a car or whitegoods, or as a result of transition in lifecycle (e.g. extra

school costs when a child starts high school).

For many people, it only takes one incident – a medical emergency,

the need for car repairs, an essential appliance breaking down, an

unexpectedly large bill or a number of bills arriving at the same time

– to tip them over the edge and to make a manageable situation

unmanageable.11

The availability of No Interest Loans to Tasmanians on low incomes is an important

way in which the Tasmanian Government is helping vulnerable households to meet

the cost pressures associated with these kinds of price shocks. The decision by the

Commonwealth Government to provide school uniform and other school cost

rebates is another example of the kind of support governments can provide to help

offset cost pressures.

If an emergency arises you have no money to put aside. You never

get on top. You end up having to borrow and the cycle goes on. If

your kids get sick it has to be on pay day, otherwise you can’t afford

it, then you have to borrow and you have to pay it back.

North East Tasmania12

Ibid keeping a phone connected was considered important for emergencies; being available to children,

families and schools, being accessible for casual work, and staying in contact with Centrelink and community

services.

10 Flanagan and Flanagan 2011

11 TasCOSS, 2009, p.30

12 Ibid, p.31

9

10

HOUSEHOLDS

Companion Report 1 identifies households that are disproportionately impacted by

the increasing costs of living, including:

Low income households

Unemployed households

Other households dependent on government pensions and allowances as the

principle source of income

Lone person households

Single parent households

Community sector reports and other data show that these households are more

likely to experience multiple cost of living risks in relation to food security, electricity

usage, transport disadvantage, housing, health risk factors and insurance. However,

it is also important to note that these households also have cost of living strengths

including resourcefulness and being good managers with the resources they have.

A common misconception is that poverty is due to poor money management, when

in fact most low income households are very good at managing their finances on a

day-to-day basis13.

Food insecurity14

The 2009 Tasmanian Population Health Survey found more than one-quarter

(28.4%) of Tasmanian adults claimed cost as the reason for not buying the quality or

variety of preferred food. 42.5% of adults in the least affluent households cited

being unable to buy the quality or variety of preferred food due to cost, compared

to only 14.0% in the most affluent households. Compared to the state average of

5%, 10% of adults in the lowest income households reported they ran out of food in

the last 12 months and could not afford a replacement.15

I pay my rent, my power, and other bills...food comes last, if there

isn’t anything left I don’t eat for days...sometimes I ration so I eat

every third day.

Geeveston community consultation16

Landvogt, K, 2008 Money, dignity and inclusion: the role of financial capability. Collingwood: Good Shepherd

Youth and Family Service.

14 Draft Tasmanian Food Security Strategy (unpublished). Food security is defined by the Tasmanian Food

Security Council as “the ability of individuals, households and communities to acquire food that is sufficient,

reliable, nutritious, safe, acceptable and sustainable”. Food insecurity can be a consequence of the cost and

availability of food, as well as access to food supplies. Cost and transport can be critical issues, particularly for

people on low incomes. People experiencing food insecurity may substitute or ration food, compromising on

the quality and/or quantity of food. In some cases meals may be missed altogether, or the support of

emergency food relief may be sought.

15 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2009 2009 Tasmanian Population Health Survey, selected

findings, Menzies Research Institute.

16 Community Inclusion Workers, 2011

13

11

The 2009 Tasmanian Child Health and Wellbeing Survey found that 4% of

households with children aged 12 years and under had experienced an occasion in

the last 12 months when their household had run out of food and could not afford

to buy more17, while 6% had experienced financial stress leading to difficulties with

food security and education expenses18. Tasmanian households where food

insecurity was more likely to have occurred included sole parent households (9%),

those with annual incomes below $40 000 (18% of those earning less than $20,000

and 14% of those earning from $20 000 to less than $40 000), jobless households

(10%), and those located in the North region (10%).

A 2009 Anglicare survey of financial hardship among emergency relief clients found

that three-quarters (76.8%) of participants always or mostly worried about whether

they could afford to buy enough food19. A shortage of money had resulted in

three-quarters (75.1%) of participants going without meals in the previous year 20,

while more than one-third (36.2%) had needed to seek assistance because of the

cost of food21. The vast majority of emergency relief clients were people dependent

on Government pensions and allowances, and many of these were long-term

recipients of social security payments22.

A 2009 TasCOSS Report found that people hardest hit by cost of living pressures

consistently go without food in order to meet other basic living costs, such as

housing, utilities, medical expenses and transport. They regularly forgo adequate or

nutritious food to make the money stretch further23:

“My kids went to school with no lunch today24.”

“Food will be the last thing. They’ll make sure that everything else is paid

and they’ll just make do on next to nothing for groceries or access

emergency relief to get them by25.”

Anglicare’s 2011 report on the cost of living for low income earners points to the

cost of food as one of the most problematic expenses for low income households.

For many research participants, food was a notional priority in the disposable

income they had left after housing and a number of other costs had been met26.

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2009, Tasmanian Child Health and Wellbeing Survey: report

of survey findings, North Melbourne: The Social Research Centre, p.28

18 Ibid, p.6

19 Anglicare surveyed 411 clients of emergency relief and financial counselling services from around Tasmania

between 20 April and 1 May 2009. Emergency relief clients are people who need to seek assistance from welfare

organisations as a result of financial difficulty. See Flanagan, K, 2009 Hard times: Tasmanians in financial crisis,

Anglicare Tasmania, p. 59

20 Flanagan, 2009 pp.50-51

21 Op.cit, p. 65

22 Anglicare Australia 2010, In from the edge: state of the family report, October, 2010, p.2

23 TasCOSS 2009 p.35

24 Ibid, p.30

25 Ibid, p.16

26 Flanagan and Flanagan 2011, pp.22-23

17

12

Many participants described rationing food by either buying less food in general, or

less fresh food than they wanted of felt they needed27.

Electricity usage

At 1 August 2010, one in three residential customers received an electricity

concession to help with the cost of their power bills28.

Low income households are more likely to use Aurora Energy’s prepaid electricity

service, Pay As You Go (APAYG)29, which is available to Tasmanians as an alternative

to standard tariffs. APAYG offers ‘time of use’ pricing30 which allows customers to

tailor their electricity consumption to cheaper times of the day and week and

maintain greater control over their electricity costs. Comparisons between APAYG

and standard tariffs are difficult to make as standard tariff customers are charged by

consumption for each tariff per quarter while APAYG customers pay according to

time of year and time of use31. However, on average APAYG prices are higher than

prices for standard tariffs32. This is principally due to differences in average

increases in network costs, the technological costs required to support pre-payment

meters, and the costs associated with maintaining a point of sale agent network 33.

In July 2009 the Tasmanian Government guaranteed that APAYG price rises for

concession holders would align with standard tariff increases, to ensure that low

income households would not be further disadvantaged34. At 30 June 2010, 40 089

(17%) of residential customers were using APAYG, of which 17 000 (42%) were

concession cardholders. This represented a higher proportion of the total number

of customers using APAYG than those on standard tariffs35. Although a changed

Ibid, p.40

Office of the Tasmanian Economic Regulator (OTTER), January 2011, Tasmanian energy supply industry

performance report 2009-10, p.179

Holders of a Tasmanian Pensioner Concession Card or Health Care Card received a rebate in the order of $340

per annum. In addition, the Tasmanian State Government made a one-off payment of $100 to customers

eligible for a concession as at 1 September 2010.

29 Ibid, p.125

The 2009 Anglicare survey of emergency relief clients reported that groups of participants most likely to be

using APAYG included households with two children (64.3%), people on Parenting Payment Single (59.6%),

public housing tenants (57.5%), single parent households (56.8%), and people aged 24 years and under (56.8%).

Groups least likely to use APAYG were people renting privately. See Flanagan, 2009, p.94

30 APAYG ‘time of use’ pricing is currently unavailable to residential customers on standard tariffs. Pricing is set in

four time blocks during the day which varies between summer and winter, weekdays and weekends. This allows

APAYG customers to shift their electricity usage in order to take advantage of cheaper rates.

31 For a full comparison refer OTTER 2011, pp.183-185

32 OTTER, December 2010, 2011 Aurora Pay As You Go price comparison report, pp.2-3

APAYG rates increased 8.8 % from 1 January 2011, which equates to approximately $100 per year for low

consumption customers and $210 per year for high consumption customers. Standard regulated tariffs

increased by 8.8% on 1 December 2010

32. Following the introduction of these higher power prices and a changed timed tariff structure for electricity

charges, paying in advance using the pre-payment APAYG option is likely to prove more expensive than being

billed quarterly. It is estimated that households could be paying up to $8 a fortnight (or $216 a year) more by

continuing to use this pre-payment option than being charged standard tariffs by Aurora.

33 OTTER, 2010, Annual Report 2009-10, p.31

34 Aurora Energy 2010, Aurora Annual Report 2009-10: customer care and billing system, p.27

35 OTTER, 2011, p.125

27

28

13

timed tariff structure for electricity charges has resulted in the pre-payment APAYG

option being more expensive than quarterly billing for standard customers,

concession card holders were still likely to find APAYG a cheaper option36.

Research undertaken by Anglicare indicates that not all concession card holders are

aware of the electricity concession and therefore are not receiving its benefit.

Although 90% of the emergency relief clients surveyed by Anglicare were eligible for

electricity concessions, only half (50.7%) received a concession. Of the survey

participants who were single parents, 66.7% did not receive a concession because

they did not know about it.37

Households in receipt of a government benefit or allowance are more likely to have

their electricity supply disconnected. In the 2009-10 financial year, 1 396 residential

customers had their electricity supply disconnected. Of these, 544 (38.9%) were

concession holders and 218 (15.6%) had been disconnected more than once within a

rolling 24 month period. Of the repeat disconnections, more than one-quarter

(28.4%) were concession cardholders38. Most disconnections were related to

inability to pay39.

A 2006 TasCOSS-commissioned survey of APAYG customers found that 23% of

customers had run out of electricity in the previous year. Single parent households

(43%) and households where at least one person was unemployed (33%) were most

at risk of running out of electricity40. Of the 345 respondents who reported that

they had run out of electricity, most (58%) had simply forgotten to recharge their

APAYG card, but one in five (21%) had found it hard to find the money for

household bills41. A 2009 Anglicare survey of emergency relief clients found that

participants using APAYG (45.7%) were more likely than participants using other

payment methods to go without heating their home or have the electricity supply

disconnected42.

The 2011 Anglicare report on cost of living notes that some households are

managing electricity consumption below the levels they need to keep their homes

warm and run important appliances due to lack of income. The APAYG meters

allow greater capacity to reduce consumption through rationing and selfdisconnection. These households will often use the emergency credit of $16 to help

them manage their electricity consumption. Some households are turning off all

appliances and lighting when they are down to their last one dollar or two of

OTTER, 2010, p.2

Flanagan, 2010, pp.104-105

38 OTTER, 2011 p.129

39 OTTER, 2008, Tasmanian energy supply industry performance report 2007-08, p.131

40 Ross, S, and Rintoul, D, 2006, Pre-payment meter use in Tasmania: consumer view and issues: a research report

carried out for the Tasmanian Council of Social Service by Urbis Keys Young, TasCOSS, Hobart, p.3

41 Ross and Rintoul, 2006, p.35

42 Flanagan, 2009, p.12

36

37

14

emergency credit43. These households are not appearing in Aurora’s selfdisconnection data.

In winter I’m always going into the emergency money. I’ve never been

disconnected but I’ve got down to $2 credit to last and turned off all the

power and used candles. But we’ve never been cut off. In winter I’m

always up at [emergency relief provider] for power money. I use Pay As

You go – it’s more expensive but you don’t have the massive bill.

Sole parent, 24 year old mother of four children44

APAYG is a popular payment method for households on low income because it

prevents customers being confronted with large quarterly power bills, however

other pre-payment options are available to standard tariff customers to help them

manage bills. These include making regular direct debits from bank accounts45 or

using Aurora Energy's direct debit, CentrePay46, EasyPay47 or PrePay48 options.

TasCOSS believe these are better alternatives to APAYG, but tend not to be as

widely publicised49.

Transport disadvantage

Low income households, unemployed households, and households dependent on

government pensions and allowances are more likely to experience transport

disadvantage50 and difficulty with transport costs such as motor vehicle fuel,

registration and insurance51. Factors affecting the level of transport disadvantage

include proximity to services, adequacy and availability of public transport services,

ability to use alternative methods of transport, and ability to access vehicles

belonging to others52 (sharing transport and getting lifts is particularly important for

low income groups53).

If APAYG customers are unable to recharge their meter they will not have access to electricity unless

supported by emergency relief services. Standard tariff customers, on the other hand, have the benefit of

extended payment options which can be crucial to cash flow management in a financially constrained

household, and allows them to remain connected to the power supply. See Flanagan, 2009, p.100

44 Flanagan and Flanagan, 2011, p.42

45 Payment is made automatically from a nominated bank account on the due date. As an added bonus, all

customers who pay their electricity bill by Direct Debit using their savings or cheque account receive the Aurora

Direct Debit Discount of $5 (5.5c per day GST inclusive) off the total bill for a standard 91-day statement period.

46 Centrepay allows customers to have fortnightly deductions made from their income support payment, which

are then deducted from their next electricity bill.

47 EasyPay allows customers to make regular, even payments, spreading the cost burden across the year and

avoiding those big bills over winter.

48 PrePay is a secure and convenient way to make advance payments against electricity charges.

49 Flanagan, 2009, p.100

50 TasCOSS, 2009.

51 Flanagan, 2009, p.81

52 Stanley, J, Stanley, J, and Currie, G, 2007 ‘Introduction’, in No way to go: transport and social disadvantage in

Australian communities, edited by Currie, G, Stanley, J, and Stanley, J, Melbourne: Monash University ePress, pp.

1.1-1.11

53 Currie, G, and Senbergs, Z, ‘Exploring forced car ownership in metropolitan Melbourne’, 30 th Australasian

Transport Research Forum, 25-27 September 2007, p.12

43

15

In 2006, only 77.5% of people aged 18 years and over in the lowest income quintile

could easily get to the places they needed to go compared with the state average of

88.1%, indicating that this group still faced barriers to accessing transport54.

TasCOSS research has found that people at particular risk of transport disadvantage

include older people, people with a disability, people with young families, children,

students and young people, unemployed people, people on low incomes, and

people with poor health55. Anglicare research had similar results, finding that

people most vulnerable to transport disadvantage include people in rural and

regional areas, people with poor health, people with a disability or families raising

children with a disability, disadvantaged job-seekers and young people56. Research

into financial disadvantage among Home and Community Care clients identified

people hardest hit by transport costs include those dependent on income support

payments, single people without their own home, people vulnerable to exploitation

by partners, and people with major health issues57.

Housing

Low income households spend a higher proportion of gross weekly income on

housing. Nationally, low-income owners with a mortgage spent 27% (or $281) of

their gross weekly income on housing costs, compared with 18% (or $384) for all

households. Low-income households renting from a private landlord spent 28% (or

$236) of their gross weekly income on housing costs, compared with 18% (or $267)

for all households58.

In order to purchase a home and service a home loan, many households now rely

on having two incomes59. Home owners or home purchasers are generally

regarded as groups less likely to be affected by financial hardship. However, the

2009 Anglicare report on emergency relief clients found that some low income

home purchasers, most of whom were income support recipients, were facing

considerable hardship. 60 The 2011 Anglicare report on cost of living also found that

low income home owners are not immune from financial difficulty. It found that the

costs directly associated with their home ownership that cause problems are rates,

maintenance costs and water and sewerage bills. Most of these households

managed the cost pressures through bill juggling and opting for small regular bill

payments and prepayment options across a range of purchases and services. 61

Low income, lone person and single parent households are more likely to rent

rather than own or purchase their home62. Public and private renters rate highly in

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, General Social Survey, Tasmania, 2006 (cat. no. 4159.6.55.001)

TASCOSS, 2009

56 Anglicare Australia 2010, p.5

57 Flanagan, 2009, p.86

58 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, Housing occupancy and costs, 2007-08: summary of findings

59 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2002, Australian Social Trends, 2002: Housing arrangements: renter households

60 Flanagan, 2009, p.94

61 Flanagan and Flanagan, 2011, p.26

62 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008, Australian Social Trends, 2008: Renter households

54

55

16

terms of disadvantage in national and Tasmanian studies63. They are among the

groups most likely to be lacking a number of essentials such as lacking a decent and

secure home, home contents insurance and being unable to buy prescribed

medication64. While older people generally have lower levels of hardship overall,

older renters experienced much higher levels of deprivation and were more likely to

go without essentials such as decent and secure housing65.

In 2007-08, more than one-quarter (26.5%) of all Tasmanian households rented

their home. Of all households, 17.2% rented from a private landlord and 6.9% rented

from the state housing authority compared with 4.5% nationally 66. Tasmanian data

suggests that public housing and private renters are over-represented in emergency

relief statistics and experience high rates of hardship.

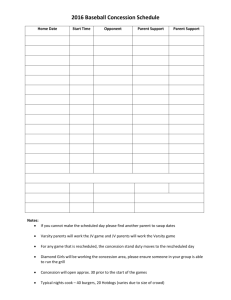

Table 1 – Hardship by tenure67

Indicator of hardship:

“this happened to participant’s household in

previous year due to a shortage of money”

Tenure

Public

housing

Private

rental

Could not pay electricity or phone or gas bill

65.3

68.4

Could not pay rent or home loan

30.8

58.1

Pawned or sold something

61.9

60.1

Went without meals

70.2

72.3

Unable to heat your home

52.6

57.8

Had the phone disconnected

34.6

41.5

Had the power off

28.3

27.3

Health risk factors

The costs associated with illness and disability can be an additional financial

burden68. For example, an unexpected illness can cause unanticipated cost

pressures as household budgets suddenly have to accommodate medical and

pharmaceutical goods and services result, sometimes exacerbated by reduced

economic circumstances (not being able to work as a result of illness or as a result

of becoming a primary carer).

63Davidson

2008 Who is missing out? Hardship among low income Australians ACOSS p.1, Saunders, P, Naidoo, Y,

Griffiths, M, 2007 Towards new indictors of disadvantage deprivation and social exclusion in Australia, Social Policy

Research Centre pp74-75; Flanagan, 2009, p27

64 Davidson, 2008, p1

65 Ibid, p.1

66 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, Housing occupancy and costs, 2007-08; State and Territory Data Cube:

Table 22 and Housing and Occupancy Data Cube: Table 3 (cat. no. 4130.0)

67 Adapted from Table 34 Flanagan, 2009, p.165

68 TasCOSS, 2009, pp.34-38

See also, Mental Health Community Coalition ACT, 2010 Submission to the National Advisory Council on Mental

Health Inquiry: ‘Daily bread income and living with mental illness’.

17

Surveys undertaken by the community sector indicate that low income households

are more likely to be embarrassed to seek medical services for fear that they would

not be able to afford the costs69.

My illness means periodically managing a roller coaster of paranoia

and mood swings. This can be challenging enough, without added

financial stress and feelings of hopelessness. When I see my

psychiatrist it costs $185.00 per half hour – simply to oversee a

change in medication. Part of this is later refunded but it’s very

difficult for vulnerable people to come up with large amounts of cash

at the very time help is needed.

Richard’s story – SANE Australia70

A 2005 Tasmanian survey71 found that single parents were much more likely than

other Tasmanians to report they had not sought health care when they needed it

and /or did not fill a prescription ordered by a doctor due to a shortage of money.

Anglicare’s 2009 survey of emergency relief clients indicated that people aged 3544 years experienced the greatest difficulty with health-related costs, with 37.1%

reporting big problems with the cost of prescriptions and 34.5% with the cost of

medical appointments72.

Couple only households were more likely to spend disproportionately more per

week (5.5%) than the state average (4.8%) on medical care and health expenses73.

This is likely to be a reflection of the older age profile of Tasmania.

The availability of concessions for households dependent on Government benefits

and allowances (eg for prescription medicines and basic hospital and medical

treatment) helps in making the cost of medical and health care manageable for

these households and has resulted in their weekly household expenditure on

medical care and health expenses being 4.1%, less than the state average of 4.8%74.

Households most likely to experience financial hardship are also more likely to have

health risk factors associated with obesity, smoking and stress.

In 2004-05, nationally, around one-fifth (21%) of adults in low-income households

were obese compared with 15% of adults in high income households 75. 32.1% of

households in the lowest income quintile smoked compared with 15.6% in the

highest income quintile76 and these households are more likely to spend a higher

TasCOSS, 2009, p.37

Hocking, B, 2011 Mental health care and poverty – intersections and policy implications, ACOSS National

Conference 2011

71 Madden, K, and Law, M, 2005, The Tasmanian Community Survey: financial hardship, Hobart: Anglicare

Tasmania, p.21

72 Flanagan, 2009, pp.124-126

73 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2003-04

(Reissue), Tasmania Data Cube (cat. no. 6530.0)

74 Ibid

75 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, Australian Social Trends, 2007: Overweight and Obesity (cat. no. 4102.0)

76 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2008, State of Public Health Report 2008, p.20

69

70

18

proportion of average weekly expenditure (2.6%) on tobacco products, compared

with the state average of 1.9%77.

Lone person households were more likely to spend slightly more on discretionary

spending items such as alcohol (3.7%) than the state average of 3.5%78.

Single parent, lone person and unemployed households were more likely to have

higher levels of financial stress than other household types 79. 46.4% of unemployed

households experienced at least one cash flow problem in the last 12 months80, and

59.5% of jobless single parent households experienced at least one cash flow

problem in the last 12 months81. Compared with the Australian average of 20%,

29% of unemployed people nationally were at a higher risk of developing mental

disorders than the Australian average of 20% and 34% of people living in one

parent families with children had a higher risk of developing mental disorders82.

Low-income households were less likely to participate in recreational activities83.

37.2% of children of single parent households participate in selected sport or

cultural activities compared with 23.2% of children in couple families; 50.8% of

children in a single parent family where the parent was not employed were even less

likely to participate compared to families where the parent was employed 27.8%84.

Insurance

Low income households are more likely to be uninsured. In 2003-04, 5% of

Tasmanian households (approximately 7 200 owner occupied households) did not

have building insurance85. Households in the bottom two income quintiles

accounted for three-quarters (74%) of these uninsured households, exposing those

households least able to afford it to greater risk in the event of loss86. Low take-up

of insurance by low-income groups may in part be due to the affordability aspect of

insurance, but also in part to the perception that these products are not for ‘people

like them’87. Non-insurance of building and contents was found to be associated

with single parent households.

In regard to health insurance, 12.3% of people without private health insurance were

likely to have found cost a barrier to purchasing their medication compared with

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006

Ibid

79 Arashiro, Z. 2010, Financial inclusion in Australia: towards transformative policy, Social Working Paper No. 13.

Melbourne: Brotherhood of St Laurence and the Centre for Public Policy University of Melbourne, p.10

See also Davidson 2008, p. 17; Lloyd, Harding and Payne (2004, pp. 10-12) in Flanagan, 2009

80 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, General Social Survey, Tasmania, 2006 (cat. no. 4159.6.55.001)

81 Ibid

82 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008, National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007

(cat. no. 4326.0)

83 TasCOSS 2009, pp. 15-16

84 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, Children's participation in cultural and leisure activities, Australia, 2009

85 Building insurance is only applicable for home-owners whose dwelling is not insured by a body corporate.

See Insurance Council of Australia, ‘The non-insured: who, why and trends’, Prepared by Dr Richard Tooth and

Dr George Barker, Centre of Law and Economics, Australian National University, May 2007, p.4

86Insurance Council of Australia, Submission to the Tasmanian State Taxation Review, Feb 2011, pp.8-9

87 Arashiro, 2010, p.7

77

78

19

6.5% of people with private health insurance. Younger people were more likely than

older people to have found the cost of medication a barrier, due in part to older

people being eligible for concessions for PBS medication 88.

‘Working poor’ middle income households

While the increasing cost of items such as housing, food, utilities and petrol have

become pain points for low-income households, middle income households are also

now at risk of financial hardships and becoming part of a growing number of

‘working poor’ households.

‘Working poor’ households are those in which people are in paid employment but

are still struggling to make ends meet89. Nearly half of working poor households

(48%) are supported by one part-time employee only, and these households are

likely to include sole parents, full-time students, people having difficulty finding

more substantial work opportunities, and those who cannot work longer hours due

to disability or illness. One quarter of the working poor (24%) live in households

with one full-time employee, and just over one-quarter (28%) live in households

with two employees of whom one is part-time90.

Working poor households are below the poverty line and often find it difficult to

maintain a reasonable standard of living, for example because of the nature of their

employment (part-time versus full-time), low levels of pay, or expenses relating to

dependent children (couples with children make up a sixty percent of working poor

households)91. While some of these households may not include recipients of

Government pensions or allowances92, others will comprise a mix of income from

wages or salaries and government pensions or allowances. These households are

also likely to include people with higher educational qualifications and couples with

children93. The 2009 Anglicare survey found that among the participants

experiencing the greatest difficulty across a range of expenses were home owners

with a mortgage, people aged 35-44 years, and families with dependent children

(couple and single parent families)94.

Some of the high and often hidden costs for the ‘working poor’ include childcare95,

maintaining a car and acceptable clothing, as well as having to buy products they

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010, Health Services: Patient Experiences in Australia, 2009; Barriers to selected

health services Data Cube: Tables 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 (cat. no. 4839.0.55.001)

89 Victorian Council of Social Service, Emergency Relief Victoria, RMIT University and Good Shepherd Youth and

Family Service 2009, Under pressure: costs of living, financial hardship and emergency relief in Victoria, p.20

90 Payne, A. 2009, ‘Working poor in Australia: an analysis of poverty among households in which a member is

employed’, Family Matters No. 8, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p 19.

91 Ibid

92 Ibid

93 Ibid

94 Flanagan, 2009, pp.8-9

95Wilkins, R, Warren, D, Hahn, M, and Houng, B 2010 Families, incomes and jobs, Volume 5: A statistical report on

waves 1 to 7 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Survey. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic

and Social Research: University of Melbourne, pp.17-18.

In 2007, 17.9% of Australian households experienced difficulties with the cost of childcare. The survey also found

that problems with the cost of childcare were persistent over time.

88

20

would otherwise have used their own labour to produce given that many work long

and unsocial hours96.

I think there’s a big gap, like I said, a gap of sorts, those in between, the

working poor ok? A gap in the system where we earn too much to be

eligible for a lot of things but we don’t earn enough to do everything

private…We are missing out because we are not in crisis.

Laura (single mother with 2 children, works part-time and studies parttime)97

Emergency relief providers reported that middle-income families were increasingly

accessing their services98, with the ‘working poor’ identified as one of the groups

experiencing the greatest increase in difficulty99.

PEOPLE

People with disabilities, their carers and families

People with disabilities, their carers and families have consistently been described as

groups vulnerable to cost of living pressures due to the strong correlation between

disability and poverty100.

By the time you pay for rent, hydro, the telephone bill, the groceries,

everything is gone. It’s really hard.

Disability Support Pensioner, Greater Hobart101

In 2009, Tasmania had the highest rate of disability of all states/territories (22.7%),

compared with a national average of 18.5%102. Rates of profound or core activity

limitation103 were also highest in Tasmania (6.8%). Nationally, 5.8% of the

population reported a profound or severe core activity limitation. Tasmania had the

second highest proportion of carers (13.3%) after South Australia (13.4%). This was

higher than the national average of 12.2%104.

Masterman-Smith, H, May, R, and Pocock, B. 2006. Living low paid: some experiences of Australian childcare

workers and cleaners, CWL Discussion Paper 1/06, Centre for Work + Life: University of South Australia, pp.5-6.

97 Arashiro, Z. 2011, Money matters in times of change: financial vulnerability through the life course, Fitzroy:

Brotherhood of St Laurence, p 2.

98 Anglicare Australia 2010, p.2

99 Flanagan, 2009, p.19

100 Saunders, Naidoo, Griffiths, 2007, Hinton, T, 2006 My life as a budget item: disability, budget priorities and

poverty in Tasmania, Anglicare Tasmania; Hinton, T, 2006 Forgotten families: raising children with disabilities in

Tasmania Anglicare Tasmania.

101 TasCOSS, 2009, p. 15

102 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, Disability, ageing and Carers, Australia: summary of findings, 2009

103 A profound core activity limitation is where the person is unable to do or always needs help with

communication, mobility or self-care tasks. A severe core activity limitation is where the person sometimes

needs help with communication, mobility or self-care tasks. See Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 ibid.

104 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, Disability, ageing and carers, Australia:

96

21

People on the Disability Support Pension (DSP) are among the highest users of

emergency relief services in Tasmania. In a recent survey of emergency relief clients,

almost 60% of people in receipt of the DSP said that they had financial problems

regularly or always, a much higher proportion than participants on other types of

income support payment. They also ranked among the groups most likely to have

more debts and experiencing the most difficulty.105

The DSP is one of the highest Commonwealth income support payments – equal to

the Aged Pension and significantly higher than Newstart or Youth Allowance

payments for example, but disability pensioners face a range of additional costs as a

result of their disability106.

These additional costs may be incurred as a result of:

The need for special equipment – eg wheelchairs, walking frames, audio

devices, custom footwear, guide dog;

Maintenance costs of equipment and assistive technology – electric

wheelchairs, grooming for guide dogs;

The need for house modifications;

The need for car modifications;

Additional transport costs – due to frequent medical appointments and

difficulty accessing public transport;

The need for medications – especially those not covered by the

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS);

The need for additional items such as continence aids and bandages;

The need for additional electricity use e.g. for Multiple Sclerosis and arthritis

sufferers who need to regulate their temperature.

There is a range of financial assistance available to people with disabilities, but this

assistance does not meet the range of additional costs incurred as a result of having

a disability. These additional costs mean that ‘secondary poverty’ is forced upon

households that would otherwise manage if they did not have the costs associated

with a disability107.

My life is total stress about everything. I have two kids with disabilities. The

pension nowhere near meets their needs. I spend $100 per fortnight just on

nappies for the two children. The pension doesn’t meet the needs of that

child and it doesn’t address the specific needs to provide for them.

Launceston Participant, Hearing the Voices108

Flanagan, 2009, pp.97-98, Cameron, P, and Flanagan, J, 2004, Thin ice: living with serious mental illness and

poverty in Tasmania, Anglicare Tasmania, p58

106 TasCOSS, 2009 p. 21

107 Hinton, 2006, p.19

108 Flanagan, J, 2000 Hearing the voices vol. 1. of the Just Tasmania series, Anglicare Tasmania, p24

105

22

With arthritis you need a warm house: that’s extra heating and extra wood

and on a pension this is too hard.

Burnie Participant, Hearing the Voices

“We go into Burnie three or four times a week. Fuel is a huge thing…When

we had Rosie in hospital for three weeks it cost us over $2,000 just with

fuel.”

Forgotten Families109

All of the families interviewed in Anglicare Tasmania’s 2007 research described

difficulties in managing on their incomes. Families were cutting back on

expenditure like insurance, food, clothing and heating. They had delayed paying

bills or negotiated repayment arrangements with creditors. Several families had

gone into debt to meet their basic needs and to pay for disability-related services110.

“At the moment I am stuck in an extremely bad cycle of debt. I have put

the rent on credit cards, paid the therapists with credit cards. I am about

to have to go bankrupt I think…. It’s been really hard in the last six weeks

where I’ve diminished all my savings to pay off the reminder of the

speech pathology and the remainder of the ABA therapists that I hired

last year. It’s a very strange position to be in where you have no money

to go and buy essentials like food”.111

People with a disability have been found to be more likely to experience:

Unemployment112, low income113, and lower socio-economic status114;

Additional anxiety and hardship with the cost of food due to specific dietary

requirements. Such foods may be more expensive to procure, and higher

levels of waste may result from particular circumstances, with associated extra

costs to the household115.

Difficulties in meeting regular housing costs, such as rates, insurance,

mortgage repayments, and maintenance costs. Additional costs were incurred

by some, through body corporate fees or the need to modify their homes for

a disability116.

Hinton, T, 2006 Forgotten Families: Raising children with disabilities in Tasmania, Anglicare Tasmania, p122

Hinton, T, 2006 Forgotten Families: Raising children with disabilities in Tasmania, Anglicare Tasmania, p128

111 Hinton, T, 2006 Forgotten Families: Raising children with disabilities in Tasmania

Social Action and Research Centre, Anglicare Tasmania, P128

112 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2009:

Second Staggered Release (cat. no. 4430.0). Also see Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2008,

State of Public Health Report 2008, p.16

113 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2008, State of Public Health Report 2008, p.16

114 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2008, State of Public Health Report 2008, p.16

115 Flanagan, K. 2009, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania, p.52

116 Tasmanian Council of Social Services (TasCOSS) 2009, Just scraping by? Conversations with Tasmanians living

on low incomes, p.24

109

110

23

Difficulty paying electricity bills (reported by 40.4% of people on a DSP in the

2009 Anglicare survey of emergency relief clients117).

Barriers to accessing transport118, despite a range of concessions and benefits

being available to them under the Transport Access Scheme. In 2006, only

71.5% of people with a core activity restriction (disability) could easily get to

the places needed. The 2009 Anglicare survey of emergency relief clients

found that ‘other’ transport costs, which included public and community

transport and taxis, were a problem for 41.0% Disability Support Pension

recipients119.

A higher risk of developing mental disorder. Nationally, 43% of people with a

severe disability were at a higher risk of developing mental disorders than the

Australian average of 20%120.

The 2009 Anglicare survey also found that households where the participant or

someone in their household had had a serious illness in the previous year had

experienced greater difficulties with health costs than those with a disability or

mental health issue (44.6% with a serious illness had reported a big problem with

the cost of prescriptions compared with 38.0% of people with a disability and 32.8%

of people with mental illness, while 38.0% of people with a serious illness had

reported a big problem with the cost of medical appointments, compared with

30.7% of people with a disability and 24.8% of people with mental illness 121). ‘Other’

transport costs were a problem for 43.2% of households where someone had

experienced a serious illness.

Seniors (aged 65 years and over)

In 2009, people aged 65 years and over accounted for 15.3% of the Tasmanian

population, compared with 13.5% nationally122. Population projections indicate that

almost one-third (30.2%) of Tasmania’s population will be aged 65 years and over

by 2041123.

The level of weekly expenditure on goods and services for households in which the

reference person was aged 65 years and over ($462) was substantially below the

Flanagan, K. 2009, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania, pp.97-98

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, General Social Survey, Tasmania, 2006 (cat. no. 4159.6.55.001)

119 Flanagan, K. 2009, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Social Action and Research Centre, Anglicare

Tasmania, p.81

120 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008, National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results,

2007 (cat. no. 4326.0)

121 Flanagan, K. 2009, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Social Action and Research Centre, Anglicare

Tasmania, p.125

122 In 2009, there were 76 900 people aged 65 years and over in Tasmania. Tasmania had the second highest

proportion (15.3%) of people aged 65 years and over among the states and territories, after South Australia

(15.4%). The proportion of people aged 65 years and over increased from 14.2% at June 2004 to 15.3% at June

2009. See Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010, Population by Age and Sex, Regions of Australia, 2009

(cat. no. 3235.0)

123 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2008, State of Public Health Report 2008, p.9 Data source:

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008, Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101 (cat. no. 3222.0)

117

118

24

Tasmanian state average of $759 for all households124. In 2003-04, these households

spent disproportionately more per week than the state average on food (20.2%

compared with the state average of 17.8%), medical care and health expenses (7.8%

compared with 4.8%), and domestic fuel and power (4.7% compared with 3.7%).125

Poverty rates126 nationally were found to be consistently high among the elderly127,

particularly single elderly people.

Seniors (65 years and over) were less likely to find cost a barrier to seeing a GP. This

may largely be due to increased government assistance for older age groups, by

way of Pensioner and Health Care Card concessions128. They were also less likely to

smoke or have a mobile phone. In 2007-08, current smokers129 accounted for 8.4%

of people aged 65 years and over, compared with 37.3% of people aged 18-24

years130. The 2009 Anglicare survey found that while 83.7% of participants had a

mobile phone, of those that did not, 74.1% were aged 45 years and over131.

Households in which the reference person was aged 65 years and over have been

found to be more likely to experience the following:

Live in a couple only household or a lone person household.

Own their home outright. Despite Tasmania’s ageing population, the

proportion of home owners without a mortgage has decreased over time,

from 42.0% in 2000-01 to 36.4% in 2007-08. The decline in outright home

ownership may, in part, be due to increasing uptake of flexible low-cost

financing options which allow households to extend their existing home

mortgages for purposes other than the original home purchase132.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2003-04

(Reissue), Tasmania Data Cube: Table 19 (cat. no. 6530.0)

125 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2003-04

(Reissue) (cat. no. 6530.0)

126 Based on the 50% median poverty line. See Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research,

University of Melbourne, 2010, Families, Incomes and Jobs Volume 5, ‘A Statistical Report on Waves 1 to 7 of the

Household, Income and Labour Dynamics of Australia Survey (HILDA), p.34

127 Note, however, that elderly people are more likely to own their own house than are younger people, and this

income poverty measure does not account for in-kind services provided by owner occupied housing. The

income poverty rates for the elderly are therefore likely to overstate the extent of their relative deprivation. See

Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne, 2010, Families, Incomes

and Jobs Volume 5, ‘A Statistical Report on Waves 1 to 7 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics of

Australia Survey (HILDA), p.38

128 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010, Health Services: Patient Experiences in Australia, 2009 (cat. no.

4839.0.55.001)

129 Current smokers include current daily smokers and other current smokers. See Australian Bureau of Statistics

2009, National Health Survey: Summary of Results, 2007-08 (Reissue); Glossary (cat. no. 4364.0). Data for current

smokers is also presented in Tasmania Together Indicator 4.3.3: Proportion of Tasmanians aged 18 and over who

are current smokers. See www.ttbenchmarks.com.au

130 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, National Health Survey: Summary of Results; State Tables, 2007-08

(Reissue); Tasmania Data Cube, Table 11.3 (cat. no. 4362.0)

131 Flanagan, K. 2010, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania, p.110

132 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2007-08: Summary of Findings

(cat. no. 4130.0)

124

25

Have high net wealth and relatively low income. Typically, wealth accumulates

with age. There is also a strong correlation between net worth and home

ownership, as for many households, their dwelling is their main asset.

Households with high net worth are more likely to own their own home with

only a small or no mortgage outstanding, and therefore only have low housing

costs133. However, people who own their own home without a mortgage can

experience difficulties in meeting regular costs, such as rates, insurance, and

maintenance costs. Additional costs may also be incurred by some, through

body corporate fees or the need to modify their homes for a disability134.

Have increased frequency of visits to GPs and prescription of medicines as age

increases135 and as the prevalence of chronic health conditions increases136.

Be uninsured. With regard to building and contents, non-insurance was found

to be associated with retiree households with a mortgage. With regard to

private health insurance, in 2007-08, 57.6% of people aged 75 years and over

did not have this kind of insurance137. Of those Tasmanians without private

health insurance, 65.1% cited cost ('cannot afford it/too expensive') as the main

reason for not insuring. Compared to other state/territories, Tasmanians were

least able to afford private health insurance138.

Spend disproportionately more on discretionary spending items such as

recreation (12.8%) than the state average of 12.5%139.

Aboriginal Tasmanians

A national study has found that Indigenous Australians are at risk of missing out on

a range of essential items, including dental care, a substantial daily meal, prescribed

medications, a decent and secure home, school activities and outings for children,

and a hobby or leisure activity for children 140.

Aboriginal Tasmanians have been identified as having lower incomes than nonAboriginal Tasmanians141 and being at greater risk of financial stress. In 2008, 31.0%

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, Household Wealth and Wealth Distribution, Australia, 2005-06; Summary

of Findings (cat. no. 6554.0)

134 Tasmanian Council of Social Services (TasCOSS) 2009, Just scraping by? Conversations with Tasmanians living

on low incomes, TasCOSS, Sandy Bay, p.24

135 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010, Age Matters, Dec 2010 (cat no 4914.0.55.001)

136 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2008, State of Public Health Report 2008, p.8

137 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, National Health Survey: Summary of Results, State Tables, 2007-08

(Reissue); Tasmania Data Cube: Table 16.3 (cat. no. 4362.0)

138 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, National Health Survey: Summary of Results, 2007-08 (Reissue); Data

Cubes: Table 19 (cat. no. 4364.0) and Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009, National Health Survey: Summary of

Results; State Tables, 2007-08 (Reissue); State Data Cubes: Table 17 (cat. no. 4362.0)

139 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2003-04

(Reissue), Tasmania Data Cube (cat. no. 6530.0)

140 Saunders, P, Naidoo, Y, Griffiths, M 2007 Towards new indictors of disadvantage deprivation and social

exclusion in Australia, Social Policy Research Centre, p52

141 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, Census Basic Community Profile Series 2006: Indigenous Profile,

Tasmania (cat. no. 2002.0)

133

26

of Tasmanian Aboriginal households were unable to raise emergency money, while

17.9% ran out of cash for basic living expenses.142

Aboriginal people have been found to be more likely to experience the following:

Food insecurity, including missing meals due to shortage of money 143.

Difficulties with utilities bills, electricity disconnections (and often not in receipt

of an electricity concession even if eligible) and being unable to heat their

home144.

Have their phone disconnected145.

The cost of wood as a problem for their household146.

Be renting their dwelling, living in public housing147 and over-represented in all

categories of the homeless population148.

Transport disadvantage – in 2002, only 78.0% of Tasmanian Aboriginal people

aged 15 years and over reported that they could easily get to places

needed149).

Participate in gambling activities150.

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Tasmanians

The 2006 Census found that 3% of Tasmanians speak a language other than English

at home. It is recognised nationally that refugees151 and people of non-English

speaking background152 face financial hardship and financial stress153 as a result of

poor access to the employment market. There is also data to suggest that people

142Australian

Bureau of Statistics 2009, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2008;

Tasmania State Tables (cat. no. 4714.0)

143 Department of Health and Human Services, 2004. Adams, D. 2009, A Social Inclusion Strategy for Tasmania,

pp.27-28, Flanagan, K. 2010, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania p48

144 Flanagan, K. 2010, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania p48, 104,105

145 Flanagan, K. 2010, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania p48

146 Flanagan, K. 2010, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania, pp.105-107

A report by the ABS on energy use and conservation found that heaters are a major contributor to household

energy costs in Tasmania, and of Tasmanian households with heaters, 26.9% were fuelled by wood.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008, Environmental Issues: Energy Use and Conservation, Mar 2008, Chapter 4

Heaters and Coolers Data Cube: Table 4.8 (cat. no. 4602.0.55.001)

147 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Housing Occupancy and Costs, Australia, 2005-06 (cat. no. 4130.0.55.001,

Table 2)

148 Chamberlain, C, and MacKenzie, D, 2009 Counting the Homeless 2006: Tasmania, Cat No HOU 208, Canberra:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. P47,48

149 Adams, D. 2009, A Social Inclusion Strategy for Tasmania; Appendix 1: The Evidence for Social Inclusion in

Tasmania, p.A1.71

150 The South Australian Centre for Economic Studies Final Report: June 2008; Social and Economic Impact Study

into Gambling in Tasmania: Volume 2 – The Prevalence Study, p.13

151 http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/2002-04/poverty/report/c15.htm,

Flanagan, J 2007, Dropped from the Moon, Social Action Research Centre, Anglicare p25

152 Flanagan, K. 2009, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania, p25

153 Arashiro, Z. 2010 Financial inclusion in Australia: Towards Transformative Policy, Social Working Paper No. 13.

Brotherhood of St Laurence and the Centre for Public Policy University of Melbourne; Melbourne, p.10

27

from Asian and other non-western countries are more likely to be uninsured for

buildings and contents154.

There are bills to pay, electricity, house rent and when you look at these

things you find that you are only left with maybe $20 for the fortnight. It

is not enough money. These are some of the things that are really hard.

Young man from Northern Africa, living in Hobart155

The problem for me, my house is very cold and the floor [has] no carpet.

Very cold. The children are sick every day in winter. Money $420 for

rent a fortnight. Very cold...it is not enough heating and it cost me a lot

of money to buy the gas.

Woman from North Africa, living in Hobart156

The Refugee Council of Australia has noted that lack of financial resources

combined with a lack of familiarity with living costs and budgeting can result in new

entrants experiencing severe poverty in their first years in Australia 157. A 2007

Anglicare report on the settlement experiences of refugees highlighted a number of

issues relating to cost of living risk158:

93% of participants surveyed were dependent on government benefits and

allowances as their main source of income.

Budgetary items most commonly cited as causing financial difficulties were

food, electricity, medicines and nappies and formula.

Transport problems limited shopping options and being able to find savings

from buying in bulk.

High rental costs were putting pressure on household budgets (even after

using financial counselling services, some participants remained in financial

stress).

Poor quality housing (including properties that were dirty, damp, leaking, had

no heating or malfunctioning wood heaters, no hot water and stoves that did

not work) was a significant problem.

154Tooth,

R and Barker, G. 2007, The Non-Insured: Who, Why and Trends, Insurance Council of Australia.

Accessed at http://www.insurancecouncil.com.au/Portals/24/Issues/The%20Non%20Insured%20-%20Report.pdf

155 Flanagan, J. 2007. Dropped from the Moon: the settlement experiences of refugee communities in Tasmania.

Anglicare Tasmania: Hobart, p. 63

156 Flanagan, J. 2007. Dropped from the Moon: the settlement experiences of refugee communities in Tasmania.

Anglicare Tasmania: Hobart, p. 67

157 Refugee Council of Australia, 2008. Australia’s Refugee and Humanitarian Program: Community views on

current challenges and future directions. Accessed at

http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/resources/intakesub/2008-09_Intake_Sub.pdf

158 Flanagan, J. 2007. Dropped from the Moon: the settlement experiences of refugee communities in Tasmania.

Anglicare Tasmania: Hobart

28

As a group, refugees have few or no assets or possessions, low income levels

and few networks of support159. In spite of this some refuges find they are

required to find a substantial proportion of their bond and rent in advance.

A recent Sudanese community forum160 noted:

Community members sacrifice food and other bills to pay urgent bills.

There seems to be a 50/50 split between the use of Aurora Pay As You Go

(APAYG) electricity and quarterly bills and there is concern that APAYG is more

expensive than quarterly bills.

Many community members pay regular (monthly) amounts to stop the shock

of large quarterly bills.

The three main cost of living stressors, in order of priority, are the increasing

cost of rent, electricity and groceries.

Covert discrimination can add to the difficulty of finding affordable and

appropriate accommodation.

Subsequent research on financial hardship in Tasmania notes that people from a non-English speaking

background appear to experience much higher rates of hardship than the general community. See Flanagan, K.

2009, Hard Times: Tasmanians in Financial Crisis, Anglicare Tasmania, p47

160 Sudanese Community Forum held in Hobart on 17 September 2011.

159

29

PLACES

People who live in rural areas significant distances from major population centres,

urban fringe areas and areas of high disadvantage, may disproportionately suffer the

impacts of cost of living increases on the basis of where they live. This is especially

likely to be the case for people living on low incomes.

Broad-acre public housing estates, traditionally located at significant distances from

major population centres, can isolate residents from essential services, and reduce

their ability to access education, employment and recreation opportunities. These

expanding urban fringe areas161 have seen population growth outstrip the

development of adequate infrastructure, such as regular public transport services.

They are characterised by high population growth rates, higher proportions of

young people (aged 18 years and under), higher unemployment and larger

proportions of families with children compared to urban and rural areas. These

areas face high demand for travel to the major urban centres for school, work and

services162.

Key issues for people living in each of areas of location disadvantage include the

absence of services and the cost of transport which combine to make a significant

impact on costs of living across the board.

Areas of low socio-economic status

In 2006, the ABS Socio-economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD)163 revealed that Tasmania had the highest proportion

The urban fringe includes the towns of Sorell, Brighton, New Norfolk, Huonville, Kettering, Woodbridge,

Exeter, George Town, Deloraine, Cressy, Longford, Perth, Evandale, Wynyard, Penguin, Ulverstone and Port

Sorell. See Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources 2007, Connected Communities: Better Bus