Conclusions, Part 1: A Long Way To Go

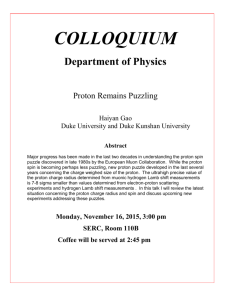

advertisement