It is important to understand how propaganda is utilized because it

advertisement

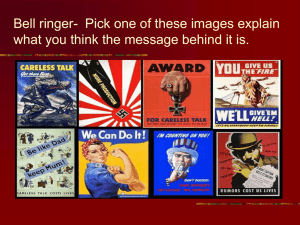

“Propagandism is not, as some suppose, a “trade,” because nobody will follow a “trade” at which you may work with the industry of a slave and die with the reputation of a mendicant. The motives of any persons to pursue such a profession must be different from those of trade, deeper than pride, and stronger than interest.” - George Jacob Holyoake Propaganda and Influence The seeds of propaganda are all around us, in the newspapers, magazines, popular culture – just about anywhere that the printed word or images can be utilized. It is used to persuade individuals or whole groups to buy, sell, love, hate, or believe in ideas about everything from toilet paper to organic foods to whole nations. Propaganda is defined by the Webster’s New World Dictionary as “any widespread promotion of particular ideas, doctrines, etc.”1 In his book The Strategy of Persuasion, Arthur E. Meyer admits that propaganda “can be based on selected truths, half-truths, or outright falsehoods, separately or in combination.”2 There is, then, no accountability in the creation and distribution of propaganda. If there is no factual basis, or at the least a shaky one, for claims that are made in propaganda, then there is no reason for concern about the misconceptions which a particular view may give birth to. Despite these outright statements about what propaganda is and how it operates, it has been, and continues to be, used to promote and to oppose political views throughout the world. Understanding Propaganda It is important to understand how propaganda is utilized because this picture gives us an understanding of not only the ideology which the author or political system is promoting but also of the social and mental control which the rhetoric of propaganda is capable of asserting over the individual as well as the masses. The debate rages as to whether or not propaganda is a correct means through which to portray an idea or a cause, especially in a democratic nation such as the United States. Should the individual be persuaded in a direction which she may not have chosen had she been able to decide of her own volition or should she be left to her own free will and thinking? Does propaganda function 1 2 Victoria Neufeldt. Webster’s New World Dictionary. New York: Pocket Books, 1995, 472. Arthur E. Meyer. The Strategy of Persuasion. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1965, 79. 2 correctly when attempting to guide a nation away from a cause which the powers that be may see as harmful to their institution, under the guise of protecting the citizens? Or is there some merit in the fact that a whole nation would need to be persuaded to loathe an institution or initiative through propaganda? These are questions which I will attempt to address through an analysis of some pieces of propaganda aimed at defaming anarchy, which was deemed a “threat” to the United States government during the period of the Red Scare. I intend to show how the propaganda exploited the history of the movement from the perspective of anarchists and how it intentionally manipulated the minds of the audience for whom it was intended. I will also question the use of propaganda by a government which is based on the foundation that people ought to be able to choose their own political parties and have the basic, unalienable right to question and even overthrow the current political system should it be seen as tyrannous. By analyzing these pieces, I hope to show how propaganda operates and the danger which it may pose in a society which claims to be based on the ideals of freedom. Means of Persuasion The means through which the propaganda is conveyed shows how much of a threat the author or governing power believes that particular movement it attacks to be. Here I will focus on pieces of propaganda which reach a wide audience. While they were printed in newspapers which not everyone would have access to, they are presented in such a way that any reader, whether educated or not, could understand the message which they are sending. Printing propaganda in a newspaper guarantees that it will be seen by a very wide audience; using an image as the focal point of the message assures that the message will be plainly laid out and easily understood by almost any reader. All one needs is a simple understanding of the cultural norms and the message becomes quite clear. One important technique which creators of propaganda utilize is repetition; their audience will be more interested in a subject if it is repeated again and again. They also use objects and 3 ideas which they know are popular and will peak the interest of the audience.3 Examples of these sorts of things include the American flag and patriotic, strong men. The accessibility and prevalence of a message also points to how much of a threat the propagandist deems it to be. For instance, propaganda aimed more at the mainstream may be seen as attacking something which is more of a threat because it is targeted at the masses and thus conveys its message openly and widely. Something which is sandwiched into corners of newspapers or has a 30-second spot on the evening news is not generally a topic which is generating much discomfort amongst individuals or the government. Surface messages are often the most powerful while the underlying messages are perhaps the more dangerous (anarchists out of the country, but anarchists always portrayed as dangerous, thus the reader may draw the conclusion – consciously or not – that all foreigners should be out of the country). These underlying messages are intentionally placed into propaganda in order to increase its impact and to make it more powerful overall. Political cartoons were used in opposing the anarchist movement in America because it was not believed to be a true and legitimate threat. It was seen as more of a threat to corporations than to government due to the fact that anarchists aimed primarily to give the worker equal rights and were responsible for forming many of the workers unions which still exist today (thought not with anarchist leanings). While the possible threat to government was addressed slightly, the message was more that anarchy would violate the individual’s rights to freedom and the freedom which democracy supplies. What this ignores is that the basic foundation of anarchy is democracy, but democracy without government. Unfortunately, government and democracy are glued in most people’s minds, making it difficult to conceive of this. Understanding the History Understanding the historical happenings surrounding instances of propaganda is important to understanding how the propaganda functioned and to whom it was aimed 3 Arthur E. Meyer. The Strategy of Persuasion. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1965, 100. 4 and how effective it could have hoped to be. History also gives us a place of origin, a set time in which to place the propaganda. The prejudices which are preyed upon are easy to identify and the intentionality of the propaganda becomes visible. An understanding of said prejudices also makes the power of the propaganda more evident and places an amount of responsibility on the author. Accountability is forced into the mind of the reader once there is a stage set upon which to view the propaganda. The pieces are no longer just words on paper that have potential power but rather actual, intentional actions which aimed to uphold some certain ideology. Governing powers are no longer seen as protecting but rather potentially disabling their people from exercising their abilities to think and reason on their own. It becomes a form of conversion rather than a suggestion. The reaction against anarchy in the United States was harsh and deliberate. Anarchists had been in America since the beginnings of the nation, but their activity in organizing workers into unions and fighting for basic rights such as housing and a living wage during the period of the end of the 19th century and into the beginning of the 20th century brought its members to the forefront of the minds of the government as well as big business. Rallies that anarchists organized were brutally attacked by police officers and even the National Guard. Attempts to rally big business and the government to take action on behalf of the workers and common people were met with violence, arrests, and deportation. In 1918, the United States government began the Palmer Raids, organized by Alexander Mitchell Palmer. These raids aimed to rid the nation of the “Reds” in general; the government did not differentiate between the anarchists and communists when applying this title. It was believed that the anarchists (who were often times referred to mistakenly as communists) were attempting to take over the nation and demoralizing its citizens. Agents would enter the homes of supposed “reds,” seize their property and throw the unlucky citizen in jail. If any evidence at all was found to connect the person to either anarchism or communism, he or she could spend a significant amount of time in jail. If the person in question was an immigrant, he or she would most likely be deported to his or her place of citizenship. December 1919 saw the greatest of these raids, and the famous anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were among the 249 immigrants who were as a result. 5 The Propaganda Following are seven political cartoons promoting anti-anarchist sentiment. Each was published during 1919 in national newspapers which are still in print, with the exception of one cartoon which was published in a local journal that has been out of print for some 80 years now. The cartoons are placed in chronological order in order to show the progression of the response to anarchy. 6 The Gauntlet Flung Down Originally published in the Brooklyn Eagle May 21, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS007.HTM 7 This first cartoon, “The Gauntlet Flung Down,” was published in the Brooklyn Eagle on May 21st, 1919. The cartoon plays on the generalization of anarchists as violent at all costs. The sign on the government building in the background (presumably the White House) says “Free Government.” This is playing on the fact that anarchists often pushed their ideas by saying that anarchy was true freedom for the individual as well as the whole. The artist, however, is saying that a capitalist democracy is true freedom – free speech, free press, and free minds. It is odd, however, that the agenda to impress the freedom of the government upon the reader is conveyed through a piece of propaganda. What does this say about the true value which is placed upon freedom if the very message of freedom is coming through the slanted, narrow means of propaganda? What is interesting to the discussion of this piece is the date in question. On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives voted on the Amendment to the Constitution which would allow women the right to vote.4 While the cartoon is clearly aimed towards anarchists, it also seems to insinuate that total chaos is about to be unleashed upon the government – and what a more perfect day to emphasize this than the day that the House votes on whether or not women should have a political say. Also, the word “free” applied solely to white male nationals for so many years that the combination of the possibility of women being allowed to vote and the anarchists growing voice in politics and labor may have instigated some nostalgia to the old days when freedom was exclusive, safe, and controlled. 4 2005 Republican Freedom Calender [online]. April 18, 2005. (http://cox.house.gov/2005_calendar/may.cfm). 8 The Bomb-erang Originally published in the Baltimore American June 21, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS005.HT 9 This piece, “The Bomb-erang,” plays yet again on the stereotype of the anarchist as violent. It was published in the Baltimore American on June 21st, 1919. The use of the American flag as a target is interesting because it focuses on two issues: the anarchists’ alleged attempts to sabotage the United States and the power of America. In Canada at this time there was a huge general strike raging. On this date, the Canadian government decided that they had had enough with the protesters. The crowds were read the Riot Act and police were unleashed upon the crowd. The day became known as “Bloody Saturday;” 30 protesters were injured and one killed.5 The author of this cartoon sends the message that America will have none of the anarchists’ rioting and protesting for the rights of the worker. Since the American flag is typically something which signifies power, unity, and safety, portraying the anarchist as throwing a bomb at the flag sends the message to the reader that anarchists are out to not only violently attack one’s person but also to attack the very principles of freedom on which the United States is founded. The flag, however, repels the bomb and sends it flying back at the anarchist, plainly showing that the power of the nation is much stronger than any attack against it. What is interesting, however, is the fact that the flag flings the bomb back, intending to injure the person of the anarchist. This sends the message that any type of resistance against the United States government will be harmful to those who instigate it. How, then, does this align with the ideals of a nation which says that its citizens ought to question the motives of the government when they could possibly be askew and whose foundation is upon the very rebellion which the anarchists were accused of portraying? 5 Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 [online]. April 18, 2005. (http://www.answers.com/topic/winnipeggeneral-strike-of-1919). 10 The Patriotic American Originally published in the Chicago Tribune June 28, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS010.HTM 11 Anarchists were often times portrayed as foreign extremists by the media. They were also labeled “bolshevists” and depicted as either Russian or German. In this cartoon, “The Patriotic American,” a line is drawn between what constitutes a true American and what a foreigner is. The American is stronger, bigger, and packs a harder punch. It is no surprise that this cartoon was published on June 28, 1919, the same day the Treaty of Versailles was signed.6 While the “foreign extremist” in the cartoon does not have discernable facial features, it follows the general stereotype of the day to assume that he is European. American labor was said to have helped greatly with overcoming the Germans in the First World War, thus the representation of American labor in the cartoon strengthens the idea that American labor is intrinsic to the nation’s success and that those who interfere with production are looking for trouble. What is interesting is that American laborers at this time did not seem to share the same feelings as the man in the cartoon; in 1919 alone over 4 million workers went on strike across the nation.7 The average American worker was not content with his pay or conditions and was letting big business know under no uncertain terms. It seems, then, that cartoons such as this may have been intended to paint a better picture than actually existed and to subvert the seriousness of the conditions of labor in America at that time. 6 Treaty of Versailles, 28 June 1919 [online]. April 18, 2005. (http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/versailles.htm). 7 A.B. Chitty and Priscilla Murolo. From the Folks Who Brought You the Weekend. New York: The New Press, 2001, 166. 12 “Say – Do I Look Sick?” Originally published in the Farm Life, Spencer, Indiana July 5, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS016.HTM 13 This next cartoon contains no direct reference to anarchy; in fact, it portrays a Russian “bolshevists” instead. I am including this piece, however, because anarchists are so often lumped in with communism (which is what the little man in the cartoon represents) because of the generalizing nature of the Red Scare. This cartoon was published July 5, 1919 – as were the following two cartoons. The birthday of the nation is often a cause for a boost in patriotism, so it is no surprise that the political cartoons published the following day were brutally “patriotic” and ethnocentric. The “Republican farmer” represents a picture of the average Midwestern American who wants nothing to do with foreign politics. This portrayal seems fairly accurate, and I am not going to take too much of an issue with it. My concern is with the title, “Say – Do I Look Sick,” and the image of the “bolshevist’s remedy.” The farmer is, first of all, assuming that his situation is the only situation there is; whether or not the author intended it, this man is representing not only Midwestern ideals but America as a whole. Perhaps what is intended here is to show how Americans ought to feel about opposing views and political ideologies. The dichotomy between a strong America and a weak – and assumed – opposition creates an image of a healthy America, one which does not need critique or modification. It would seem, though, that if America were in such a great condition economically, socially, and politically, there would not have been so numerous amounts of strikes or race riots or political scares. Political cartoons such as this one sought to reassure the reader that America was in deed in a good place. 14 “Come Unto Me, Ye Opprest!” Originally published in the Memphis Commercial Appeal July 5, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS017.HTM 15 “Come unto Me, Ye Opprest!” plays upon the idea of American freedom and liberty and creates a dual interpretation of the phrase – one patriotic and one more sarcastic. The cartoon contains a picture of the Statue of Liberty, which is our monument to the freedom and possibilities of the United States. Behind her back, however, crouches the anarchist, ready to throw his bomb and blow her to bits or stab her to death with his knife. Anarchy was generally seen as something which came from across the seas; therefore, aliens were to be feared and met with caution. This view ignores the fact that many prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman became anarchists after having come to America and experienced life as a factory worker or seamstress. The threat, then, does not seem to be so much in who the government allows into the country as much as it is in the way that workers were treated. By placing the Statue of Liberty next to the dangerous looking anarchist, the author of this piece is juxtaposing two seemingly opposing views, painting a picture of the anarchist as attempting to destroy the peace and harmony which the Statue of Liberty represents for the United States. The artist seems to be playing on the idea of anarchists preying on America much like a dangerous man would prey on a woman. Most often anarchists were portrayed as men (unless the particular piece was depicting Emma Goldman). It was not until later in the Red Scare that images of women as accomplices began to creep into the “anti-Red” propaganda. Note that the anarchist is a bearded man and the Statue of Liberty wears an innocent, unaware look on her face. America, then, is above suspicion and the anarchist is to be guarded against. 16 Close the Gate Originally published in the Chicago Tribune July 5, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS018.HTM 17 This next image is overtly racist and does not even attempt to hide exactly what it is impressing upon the reader. We see again the image of the bomb – a usual representation of an anarchist. According to this image, he is “undesirable” and ought not to be allowed into the country. The same point may be made for this piece as the previous; anarchists often times became anarchists after living in America for some time. Assuming a superethnocentric view on immigration could not help to slow the growing force of anarchy and political protest; a reformation of social conditions would do a much better job on this front. The reader is being told in this situation that immigration and immigrants are both to be looked down upon. It is interesting to note that the untouchable caste in India is referred to sometimes as “undesirable.” This seems to be a direct acknowledgement that immigrants are poor, which gives the piece a classist as well as racist connotation. This image is disconcerting because it is a reoccurring type of image in American propaganda which demands for stricter borders. The immigrant is almost always pictured as dangerous and as a type of person whom we do not want to enter the borders of our nation. 18 Boosting Him Up Originally published in the Philadelphia Inquirer October 4, 1919 This may be viewed online at the web address http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS063.HTM 19 This final piece speaks again on the power of anarchy in protests. During the date on which this was published, October 4, 1919, America was witnessing the 1919 Steel Strike.8 It had begun on September 22, 1919 and did not show any signs of letting up on the day that this cartoon was published. By this time, over 365,000 steel workers across the nation had walked out on their jobs. Anarchists were blamed for instigating the strike; indeed, the strike was organized by the American Federation of Labor, an organization which was notoriously known as infiltrated by “Red radicals.” This cartoon places “bolshevist propaganda” as the foundation for strikes, which in turn enable anarchy to unleash its destructive power against America, which is again represented by the American flag. Anarchy was portrayed as being held up by false doctrines and as meddling with the affairs of the common worker. Big business, the government, and the media alike would have liked the average factory worker to accept his position and not ask questions; the anarchist brought to the workers’ attention and the attention of business owners, government officials, and the media exactly how bad the condition of the worker was. One might say rightfully, then, that the anarchist deserved to be described as interfering, meddling, and even as an annoyance; they did not, however, have an agenda in these circumstances other than fighting for the rights of the workers. Thus, pieces of propaganda such as this one were used to persuade the public that the anarchists were aiming to ruin the nation rather than build up the strength of the worker. Could it possibly be that this strength is what they feared? 8 A.B. Chitty and Priscilla Murolo. From the Folks Who Brought You the Weekend. New York: The New Press, 2001, 168-9. 20 Drawing Conclusions I have intentionally left questions unanswered in hopes that you, the reader, will engage with the text and draw conclusions of your own. It is important, however, to understand the purpose of these separate pieces when they are looked at together. A democratic, free nation such as the United States has used propaganda in this form since the beginning of printed media. Is this method of conveying a political message correct or is there some discrepancy between what the United States claims to be and how they act? Freedom of choice is one of the most important freedoms which this nation boasts, so it is odd that the readers of these political cartoons are being intentionally led in a direction, commonly without a clear understanding of the matter at hand. These ideas and stereotypes were conceived by the government, passed to the media, and then projected to a very wide audience. It is important as well to look not only at the past but to also ask questions about our present conditions and what they may lead to in the future. Over 80 years after these political cartoons were published, I am writing about their negative influence on the minds of the American people and on whether or not this is a proper way in which to promote the democratic ideologies of our nation. We must then ask ourselves if we are comfortable with the idea that the propaganda that is being used today to subvert political movements may someday be scrutinized through different lenses but with the same intent – to uncover how influence is exerted through propagandist messages. If accountability will not come from within the field of propaganda, as has already been stated, then there must be accountability from the outside. As citizens of a democratic nation, we should scrutinize the messages which are passed down to us from the media and government in order to extract the positive and negative messages and, further, to decide which parts are legitimate and which are not. In doing this, we as a people will gain a better understanding of how propaganda operates in society around us and how we can avoid falling into its clutches in the future. 21 Works Cited 2005 Republican Freedom Calendar [online]. April 18, 2005. (http://cox.house.gov/2005_calendar/may.cfm). Bernhard, Nancy E. U.S. Television News and Cold War Propaganda, 1947-1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Bomb-erang [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS005.H TM). Boosting Him Up [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS063.H TM). Chitty, A. B. and Priscilla Murolo. From the Folks Who Brought You the Weekend. New York: The New Press, 2001. Close the Gate [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS018.H TM). Gauntlet Thrown Down, The [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS007.H TM). Goldman, Emma. Anarchism and Other Essays. Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1969. Look Sick [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS016.H TM). Meyer, Arthur E. The Strategy of Persuasion. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1965. Meufeldt, Victoria, ed. Webster’s New World Dictionary. New York: Pocket Books, 1995. Patriotic American, The [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS010.H TM). Treaty of Versailles, 28 June 1919 [online]. April 18, 2005. (http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/versailles.htm). 22 Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 [online]. April 18, 2005. (http://www.answers.com/topic/winnipeg-general-strike-of-1919). Ye Oppressed [online]. March 12, 2005. (http://newman.baruch.cuny.edu/digital/redscare/HTMLCODE/CHRON/RS017.HTM).