IDEO success guide

advertisement

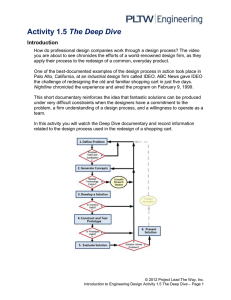

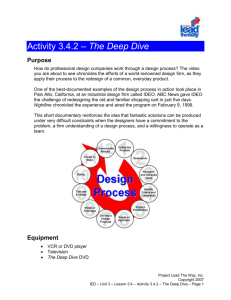

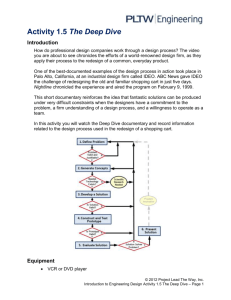

Shannon O’Leary Lawrence University PNACP 2011 Go-To Guide Strategies for solving problems/making progress in physics research Prepared by Doug Martin and Shannon O’Leary, following Nightline’s “Deep Dive”, a 20 minute segment about the design company IDEO in their 5-day quest to design a better shopping cart. Also included is the combined research experience of Professors Brandenberger, Collett, Martin, O’Leary, Pickett, Stoneking, and Clausen. (i) Identify the problem in need of a solution such as some system that needs replacing, or a computer routine that requires too much user involvement, or this post needs to be damped, or this laser needs to be less noisy. This problem should be well defined. In the Deep Dive, the participants were simply given a problem: Build a better shopping cart. (ii) Background phase: your goal is to think broadly about the problem, the origins of the problem, and reasons why you seek a solution. Deep Dive showed a broad-ranging discussion of issues with the current system, with the statement “Everyone has good ideas.” Some questions to ask yourself: what are the issues with the current system? (discuss with peers, self, advisors, etc.) what the required parameters of the solution (e.g. RMS noise of less than 1%)? If 1% is really necessary, fine. If 1% would be nice but 3% would be ok, do not make extra work for yourself. what is the background behind the problem.? Why do you need <1% RMS noise? What type of measurement will that enable? Is there another way to make the same measurement? Is there another way to conceive of the experiment? Who are experts who may have already dealt with the problem? These experts may include advisors, peers, other researchers (reports in the literature), etc. Some preliminary actions to consider: Keep active: work on other things and live with the problem for a while. Sometimes you’ll find solutions in related issues. Write up carefully what you have already done, up to the point you became stuck. Talk to smart people (your peers, advisors, friends). Explain where you are and how you got there, not what the problem is. Build a flow chart or story board of the system you’re working on, and identify unknowns. Draw out what you actually built/programmed. Then compare that to what you thought you did. Implement a simple, partial, temporary fix. (iii) Search for solutions (brainstorming). Once you’ve defined the problem and the reasons you seek solutions, you’re ready for a brainstorming session such as the Deep Dive itself in Deep Dive. Gather your audience, and prepare them: Present a specific problem; the reasons you want to solve it (e.g. we need to measure the line-width of a narrow transition); the history of past attempts, etc. Rules for successful brainstorming: shannon.oleary@lawrence.edu Shannon O’Leary Lawrence University PNACP 2011 Your problem must be well defined, but with an answer that is not simply a matter of more study on your own part (a poor example might be “I need help understanding interference phenomena”). Your audience must have some experience or expertise to bring to bear. Your preparation is essential to draw out constructive ideas. Once the stage is set, the goal is to encourage a large number of wild ideas (go for quantity). The rules IDEO sets are: o One conversation at a time (only one person talks at a time) o Stay focused on the topic at hand (only present ideas related to the brainstorming target) o Encourage wild ideas (but outlandish ideas are great) o Defer judgment (now is not the time to evaluate ideas, just to get them down) o Build on the ideas of others (if someone else has a good idea that you can enhance, suggest it) o Be visual (this is not an explicit rule, but lots of ideas have drawings associated with them, and are better communicated visually) In Deep Dive, one person is in charge of writing down the ideas – on a whiteboard, if possible – and also in charge of immediately stopping evaluation of ideas (with the bell). Finally, capture the range of ideas by copying them into your lab book, or taking a picture, printing it out, and copying that into your lab book. (iv) Evaluate and refine the possible solutions. In Deep Dive, mention is made of a time for grownups – this is it. Collect related ideas, and rank all of the ideas from the brainstorming session. Some possible ways to rank: which have the highest probability of success in the time available? Which have the biggest potential payoff? Which must be addressed before others can? You need to be realistic about what is doable in the time you have! Select one or two solutions to work on, but be prepared to return to the drawing board if they don’t pan out. The IDEO quote is “Adults take over to stop the cycle.” (v) Prototype. Build as simple, as quick and dirty, a solution as you possibly can. Your goal is to figure out whether this idea has any possibility of success, not to produce the perfect solution. There is real danger in doing everything down to the last epsilon and sigma at this point – you can spend days or weeks perfecting a prototype that doesn’t solve the problem! Remember that IDEO dictum, “Fail often to succeed sooner.” (vi) Refine. In Deep Dive, all the first prototypes had strengths and weaknesses, and all needed to be redone. David Kelly said “More work must be done before you can continue.” Expect your advisor to step in and demand substantial revision. This idea of revision is critical – successful innovations are not born, Athena-like, perfect on the first attempt. Instead, a successful innovation requires lots of hours and lots of hard work. On that dour note, remember that Deep Dive also has words of wisdom like, “Fresh ideas come faster in a fun place,” and “being playful is of huge importance!” Expect this summer to be filled with hard work, but that work will be more bearable if you have fun along the way. shannon.oleary@lawrence.edu