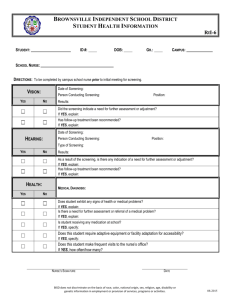

CDPHE Vision Screening Guidelines for Infants and Toddlers

advertisement