The incredible world of millipedes

advertisement

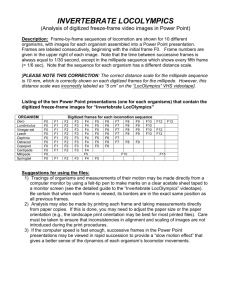

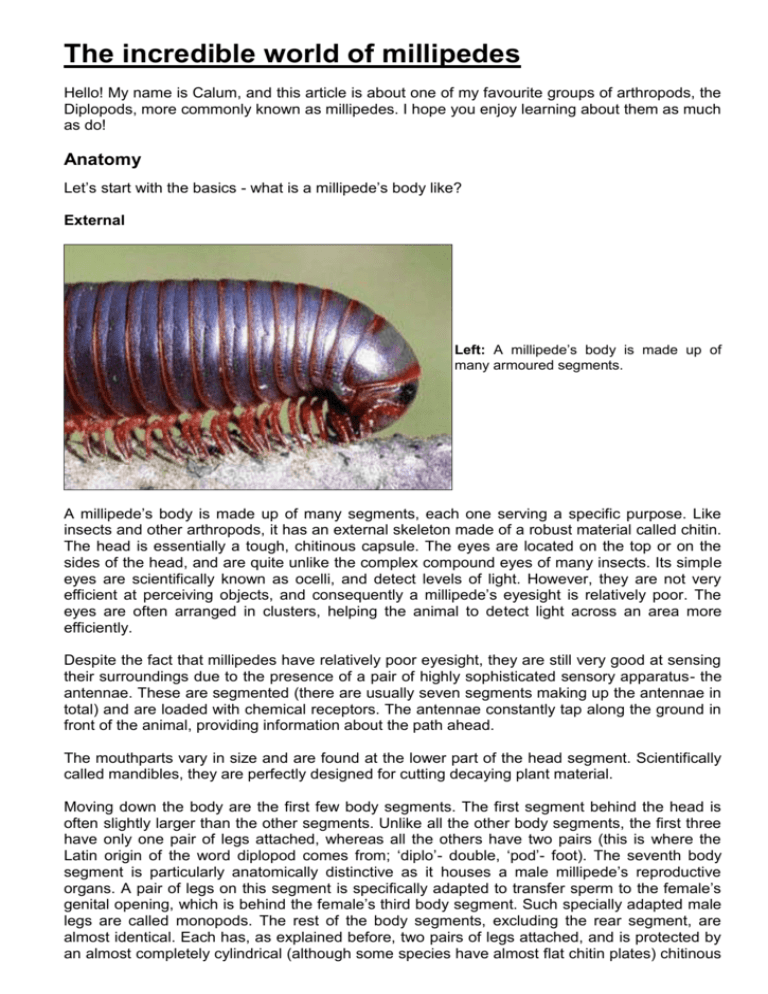

The incredible world of millipedes Hello! My name is Calum, and this article is about one of my favourite groups of arthropods, the Diplopods, more commonly known as millipedes. I hope you enjoy learning about them as much as do! Anatomy Let’s start with the basics - what is a millipede’s body like? External Left: A millipede’s body is made up of many armoured segments. A millipede’s body is made up of many segments, each one serving a specific purpose. Like insects and other arthropods, it has an external skeleton made of a robust material called chitin. The head is essentially a tough, chitinous capsule. The eyes are located on the top or on the sides of the head, and are quite unlike the complex compound eyes of many insects. Its simple eyes are scientifically known as ocelli, and detect levels of light. However, they are not very efficient at perceiving objects, and consequently a millipede’s eyesight is relatively poor. The eyes are often arranged in clusters, helping the animal to detect light across an area more efficiently. Despite the fact that millipedes have relatively poor eyesight, they are still very good at sensing their surroundings due to the presence of a pair of highly sophisticated sensory apparatus- the antennae. These are segmented (there are usually seven segments making up the antennae in total) and are loaded with chemical receptors. The antennae constantly tap along the ground in front of the animal, providing information about the path ahead. The mouthparts vary in size and are found at the lower part of the head segment. Scientifically called mandibles, they are perfectly designed for cutting decaying plant material. Moving down the body are the first few body segments. The first segment behind the head is often slightly larger than the other segments. Unlike all the other body segments, the first three have only one pair of legs attached, whereas all the others have two pairs (this is where the Latin origin of the word diplopod comes from; ‘diplo’- double, ‘pod’- foot). The seventh body segment is particularly anatomically distinctive as it houses a male millipede’s reproductive organs. A pair of legs on this segment is specifically adapted to transfer sperm to the female’s genital opening, which is behind the female’s third body segment. Such specially adapted male legs are called monopods. The rest of the body segments, excluding the rear segment, are almost identical. Each has, as explained before, two pairs of legs attached, and is protected by an almost completely cylindrical (although some species have almost flat chitin plates) chitinous plate. The rear segment bears a pair of plates that cover the millipede’s anus, which open outwards during excretion. Internal Now let’s have a look at what’s inside a millipede. As I said before, only the outermost layer of the exoskeleton is visible. This layer is made up of dead cells and is hardened with calcium carbonate crystals. This robust exterior provides the millipede with a little defence against predators. The layer beneath is more flexible and absorbs shock from bumps and falls. The more flexible chitin that makes up this layer also provides added flexibility to the millipede’s body. The innermost layer is made up of epidermis. The cells here produce the chitins for the outer layers of the exoskeleton. The internal organs are many and each does its job very well. After being eaten and dealt with by the mandibles, food enters the three part digestive tract. After food is digested by the foregut, the mid-gut and the hind-gut, nutrients enters the bloodstream (or rather, ‘haemolymphstream’). The heart is a long, dorsal tube. Waste is removed from the blood by special organs called malphigian tubes, which then transport the waste to the rectum, after which it can be excreted. The nervous system is particularly complex. The body is controlled by a three part brain, and attached to it is a nerve chord that runs the length of the entire body. Attached to this nerve chord are nerve clusters responsible for leg movement. Above: This species of millipede is scientifically known as Archispirostreptus gigas, and is common in the entomological pet trade. Millipedes respire in a similar way to insects. Oxygen enters the body through tiny exterior holes, called spiracles. These lead to an extremely complex system of internal tubes which carry oxygen to all the parts of the body. Carbon dioxide is expelled through the tube system (the tubes are called trachea) and out of the body through the spiracles. This system is not very efficient, and it is believed by scientists that the inefficiency of this system is why millipedes (and insects) do not grow very large, as such a system can only function well in a smaller body. Millipedes also possess glands that produce noxious chemicals as a defence against predators. These glands, called metathoracic glands, contain different compounds depending on the species of the millipede. Group history The fossil record contains relatively few millipedes, possibly due to the fact that they live in habitats where fossilization is unlikely to take place. In the moist conditions in which the vast majority of millipedes live, animal remains usually decompose very fast. It is now widely believed that myriapods (millipedes, centipedes and relatives) evolved from aquatic arthropods. The fossils of myriapod-like arthropods have been found in rocks dating from the Cambrian period, and the first terrestrial myriapod fossils date from the late Silurian period. However, burrows have been discovered in late Ordovician rocks that may have been made by myriapods. If the burrows did belong to primitive myriapods, that would make the group millions of years older. The very oldest fossil millipede is called Pneumodesmus newmani, and, at 425 million-yearsold, this may be the very oldest terrestrial animal in the fossil record! Pneumodesmus newmani is also the oldest arthropod to possess a tracheal respiratory system. The first back-boned animals did not appear on land until 50 million-years later! Primitive myriapods would have lived amongst the first plants to get a foothold on land. Also living amongst the liverworts and moss-like plants were other arthropods, such as early terrestrial scorpions. Centipedes appear in the fossil record ten-million-years after Pneumodesmus newmani. Apart from altering their respiratory systems, the millipede’s ancestors probably needed to change very little to become terrestrial. Their segmented legs would have been just as functional on land as in water, and their chitinous bodies could support themselves on land as well as in the sea. As they do today, the primitive millipedes would have fed on plant material. At this stage, the plants amongst which these arthropod pioneers had created their basic ecosystems were only about five centimetres tall. But as more, larger plants evolved, the millipedes’ habitats became more complex. With new habitats evolving, millipedes could diversify into the wealth of species we know today. Above: There are thousands of millipede species alive today, perhaps because of the fact that they have been around for so many millions of years. In this time, some have diversified into vibrant forms, such as this appropriately named Red-Legged Millipede (unknown sp.). Ecological niche and diet Left: The RedLegged Millipede is more of a specialist species, feeding exclusively on decomposed plant material. Despite their huge variety in shape and size, the majority of millipedes hold a similar ecological niche- a ground-dwelling detritivore/herbivore, situated relatively low-down in the food-chain. A detritivourous (or saprophagous) animal is one that feeds on dead or decaying organic matter, and a herbivorous animal feeds on living plants. As with other animals, some millipedes are relatively specialised, whereas others are generalists, feeding on decaying plant material, including decaying wood and leaves, fallen fruit, fungi, animal dung, and even carrion. A few species have even become carnivorous, feeding on smaller invertebrates and moving a little up the food-chain. Development and survival Millipedes usually lay their eggs where there is plenty of decaying plant material. Some species lay their eggs in nests in the leaf litter, so the young have an immediate source of food when they hatch. During embryonic development, pairs of body segments, each bearing one pair of legs, fuse, producing the four legged segments that give diplopods their name. Most species hatch with only six legs, gaining legs and body segments as they shed their exoskeletons. A millipede would make an ideal meal for many animals, and so many have developed intriguing defence strategies. Many excrete chemicals produced in their metathoracic glands from between their body segments. Although many of the compounds produced are not very efficient at protecting the millipede from some predators, a few species can produce powerful chemicals including cyanide. Other species have developed particularly thick chitinous armour. Plated millipedes have a plate that extends laterally outwards on every body segment, and pill millipedes can curl into a tight ball with their head tucked under their last body segment, protecting the millipede’s underside and leaving only tough plates of hardened chitin exposed. Left: Millipedes curl into a tight coil when threatened, often excreting chemicals from their thoracic glands at the same time. Bye for now! From Calum Lyle, 9FNS Article originally appeared in Bug Club magazine, published by the Amateur Entomologists' Society and reproduced with kind permission.