Conquest of Mexico and Peru

advertisement

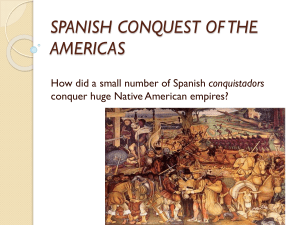

The Conquest of Mexico: 1519-1521 Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec empire was actually a five-mile island located in the valley of Mexico. It was a beautiful city containing botanical gardens and zoos. It was kept very clean. Nightsoil (human poop) and garbage were hauled away, the streets were cleaned, and most people bathed daily. Its population was between 80-250,000. Only four European cities were larger. The population of Mexico was 30 million. France at the time was 20 million, and Spain was 8 million. The Aztec empire was actually a coalition of city-states that paid tribute such as food, clothing, gems, and gold to the imperial center. Conquered towns provided soldiers and slaves, and Huitzilopochtli had to be recognized as the supreme deity. Otherwise, the Aztecs did not interfere in the religious practices, internal affairs, or traditions of those they conquered. This lack of unity in the Aztec empire turned out to be a fatal weakness. Tales of the riches of Mexico piqued the interest of many, including Hernando Cortes, a minor official in Cuba. Going against the orders of his superior, Cortes set sail in February of 1519 with 11 ships, 500 men, 16 horses, and 14 cannon to search for gold and other treasures. They landed on the island of Cozumel, where Cortes hooked up with Jeronimo de Aguilar, a survivor of a 1511 shipwreck who now had knowledge of the native language and customs. The first battle between the Indians and the Spaniards occurred at Potonchan (Tabasco). Although many Spaniards were wounded, only two died. However, 200 Indians died at that battle. The Indians believed the Spanish to be invincible. The real secret to the Spaniards’ success was superior technology. The Indians fought with weapons made of wood, while the Spanish had cannons, guns, metal helmets, metal breastplates, and horses. In addition, the Indians were awestruck by the Spanish. They believed the ships were giant birds and the men on horseback were a single animal – half-beast and half-human. They marveled at the magic sticks that made smoke and caused death. This created a great psychological advantage. Among the many gifts the Spanish received after this battle were 20 maidens. A woman the Spanish baptized as Marina (known to the Mexicans as La Malinche) knew Indian languages unfamiliar to Aguilar. She became Cortes’s mistress and advisor, and even eventually bore him a son. La Malinche became a traitor to Mexico. (The Spanish word for traitor is Malinchismo.) Tenochtitlan was 200 miles away, in the interior. However, Montezuma was well aware of the Spaniards’ activities. Cortes told a local chief to send word to Montezuma that the Spaniards “have a disease of the heart which could be cured only by gold.” It took runners only a day and half to inform Montezuma, who sent gifts back to Cortes along an apology that he would not be able to meet him because he was “feeling ill”, but he wished him well. Cortes continued up the coast and founded a settlement La Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz. Here he was joined by another ship from Cuba with 60 additional men and nine more horses. At this point, Cortes was ready to head inland and conquer the prize. But he had a serious legal problem. Spaniards must have royal permission to set out on explorations. Although Governor Velazquez had originally granted Cortes a commission to explore Mexico, he had revoked it. Cortes had ignored Velazquez and gone anyway. He was an outlaw, who was now willing to gamble everything, hoping all would be forgiven in the event of a glorious conquest. Cortes wrote to the king, telling of his progress in Mexico and his personal devotion. He sent off the letter and the treasures he had accumulated on a ship bound for Spain. At this point, some of Cortes’s men plotted a mutiny to return to Cuba. When he found out, Cortes had two of the men hanged, the feet cut off another, and 200 lashes given to many others. Only minor participants went unpunished. To assure the full support of the rest of his troops, Cortes shared all his supplies with his men and promised them a share in the booty. Then, just to fully ensure their loyalty, he had all the remaining ships wrecked. There was no going back. Leaving old and disabled men to manage Vera Cruz, Cortes and his troops set out for Tenochtitlan. In the meantime, Montezuma was getting pretty nervous. As if the tales of Cortes’s exploits were not enough, he was burdened by an even more ominous tale. According to Aztec legend, the feared plumed-serpent god Quetzacoatl was destined to return and claim the Aztec kingdom. Legend foretold that the ambassadors of Quetzacoatl would have white skin and beards. And by a fatal coincidence, according to the Aztec calendar, the year of Quetzacoatl’s promised return was the same year Cortes docked on the Mexican coast. The 200 mile trek to Tenochtitlan was a harsh, 7,500 foot climb from the tropics to the highlands, which was marked by minor skirmishes. It was around this time that Cortes first witnessed the practice of human sacrifice. When word reached Montezuma that the Spaniards were revolted by this custom, he was reminded that Quetzacoatl also abhorred sacrifice. Nevertheless, Montezuma ordered more sacrifices and magic to be used to halt the Spanish, but when these strategies failed, he ordered that the Spanish be given whatever they desired. The Spaniards stopped in the town of Cholula before continuing on to Tenochtitlan. Apparently, upon the orders of Montezuma, the Cholulan nobility were conspiring to eliminate the Spaniards. When Cortes received word of this he retaliated by killing 6,000 Cholulan warriors in a five-hour battle along with any women and children that got in the way. The massacre at Cholula was a turning point. Montezuma now made only half-hearted attempts to halt the Spanish, and Cortes had increased selfconfidence. This tragedy is blackest mark against Cortes, since most Mexicans believed he acted without provocation. To further unnerve the Aztecs, Cortes spread the rumor that the Spaniards don’t sleep or remove their armor. Montezuma was in a hopeless position. Although he could easily assemble an army large enough to defeat the Spanish, he hesitated. If the Spanish were the divine agents of Quetzacoatl, he would suffer even worse consequences. When the Spaniards reached Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, Cortes and Montezuma finally met and exchanged necklaces. Montezuma greeted Cortes as Quetzacoatl and welcomed him back to his throne. Although the Spaniards were well treated in Tenochtitlan, they realized they were essentially trapped in the city. The Aztecs became incensed when they were forced to stop their practice of human sacrifice and when their idols were smashed and replaced with crosses and images of the Virgin Mary. To ensure his safety, Cortes took Montezuma hostage, but allowed him to continue to rule his people. When Cortes received word that Velazquez was furious over his rebellion and had sent Panfilo de Narvaez to arrest him, he took half his troops (140 men) and returned to Vera Cruz. Immediately upon his arrival in Vera Cruz at midnight in a rainstorm, Cortes, Narvaez, and their respective troops engaged in a frenzied skirmish that ended when Narvaez got a pike in his eye and surrendered. This brief battle further enhanced Cortes’s prestige among both the Indians and Narvaez’s men who were eager to serve under him. Cortez was ready to return to Tenochtitlan, even before he heard that the Spaniards were pinned down in their quarters. Pedro de Alvarado had been left in charge in Tenochtitlan. When he heard that the Aztecs were planning to sacrifice the Spaniards after a religious festival, he elected to strike first. During the celebration, the Spaniards blocked the exits, drew their swords, and rushed the celebrants. In a wild and bloody scene, 200 Aztec nobles were killed. The Spaniards retreated to their quarters, where they were besieged by thousands of grief-stricken and enraged Indians. Montezuma used his last bit of influence to save the Spanish from annihilation. Cortes returned and entered the city unopposed. He was in the company of a thousand men, many of whom were Indians, and one-hundred cavalrymen. Inside the confines of the city fighting broke out. Cortes urged Montezuma to go up on a rooftop and convince the Aztecs to desist. By Spanish accounts, Montezuma was stoned to death by fellow Aztecs as he was appealing for peace. According to Indian sources, he was strangled by the Spaniards for refusing to cooperate. At any rate, in Mexican history Montezuma is viewed as less than heroic and is blamed for not resisting the Spanish. Fighting was at a standstill, and the Spanish were just about out of food and gunpowder. Unfortunately, the Aztecs rejected a truce, and retreat seemed too risky. Cortes planned an escape. On July 1, 1520, around midnight, in heavy fog and light rain, the Spaniards attempted to leave Tenochtitlan along the shortest route, a two-mile long portable bridge. Their horses’ hoofs were covered in cloth, and they were quietly making their way across when an old woman saw them and cried out. Thousands of Aztecs attacked, utter chaos ensued, and the portable bridge collapsed. That night alone, 450 Spaniards died, and within four days another 400 were killed. The event became known as El Noche Triste (the Sad Night.) In April 1521, Cortes began another assault on Tenochtitlan. He was aided by Spanish reinforcements from Cuba and thousands of Indians eager to overthrow their old masters. After a four-month siege, wherein the Aztecs fought with extreme bravery, the last Aztec emperor, Cuauhteoc (nephew of Montezuma) surrendered on August 23 amidst his starving people. Cortes took possession of the ruins that had once been the city of Tenochtitlan. The Conquest of Peru: 1531-1533 After Pedrarias Davila founded the town of Panama on the western side of the isthmus, it became a base for exploration on the Pacific coast. The Spaniards began hearing legends of a land of gold called “Biru.” The crown authorized an illiterate soldier of fortune named Francisco Pizarro to lead an expedition in search of this new land of gold. In December 1531, Pizarro left Panama with a force of about 200 men and arrived on the Peruvian coast several months later. He soon learned of a civil war that had ripped apart the Inca Empire. Two half brothers, Atahualpa and Huascar, were fighting over the throne. Atahualpa had defeated his elder brother Huascar in a particularly bloody war and had taken him prisoner. As Atahualpa was advancing on the imperial capital of Cuzco, he received news that white strangers had come. After an exchange of gifts, the armies of Pizarro and Atahualpa prepared to meet in the mountain town of Cajamarca. While Montezuma’s great mistake was passively accepting the divinity of the invaders, Atahualpa’s fatal error was underestimating the military strength of the small Spanish army. He had been led to believe that the Spaniards’ swords were no more dangerous than weaving battens, that the guns were only able to fire two shots, and that the horses were powerless at night. Although the meeting had been planned for noon, Atahualpa and his troops arrived at dust, (possibly to eliminate the threat of the horses). Atahualpa found the town square deserted, because Pizarro had cleverly concealed his men in the buildings around the square. A priest through an interpreter began badgering Atahualpa about his obligations to the Spanish king and the Christian God. In frustration, Atahualpa threw down a Bible they had given him. At that point, Pizarro gave his signal. The Spanish soldiers, cavalry, and artillery rushed out and began killing hundreds of terrified Indians. Atahualpa was taken prisoner. In an effort to gain his freedom, Atahualpa offered Pizarro a room full of gold as his ransom. Hundreds of llama-loads of gold began arriving from all throughout the empire. However, even after the room was filled, Pizarro kept Atahualpa under “protective custody” as a puppet ruler. Unfortunately, this situation did not work out as planned. Atahualpa became the focal point of a conspiracy to overthrow the Spanish. Thus, it was decided that Atahualpa must die. He was charged with treason and condemned to death by burning. However, on account that he had become a Christian, his sentence was reduced to strangling instead. Following Atahualpa’s death in November 1533, the Spaniards captured and pillaged the Inca capital of Cuzco. The gold and silver looted from Cuzco, together with Atahualpa’s enormous ransom of gold was melted down and distributed among the soldiers after King Charles V got his royal share. Pizarro attempted to establish another puppet regime by proclaiming Huascar’s brother Manco as the new Inca emperor. However, Manco refused to participate in this farce and began a ten-month insurrection against the Spaniards in Cuzco. Although they came close to winning back the Inca capital, the combination of superior Spanish weapons and food shortages proved to be too much for the Incas. Manco retreated to a remote stronghold in the Andean mountains, where he and his successors maintained a government in exile until 1572, when the last Inca emperor, Tupac Amaru, was captured and beheaded. Interestingly, other Tupac Amarus would come along later. In 1780-81, Tupac Amaru II, who claimed to be a descendant of the original, led a bloody revolt with about 80,000 Indians against the colonial powers in southern Peru and Bolivia. There was also an urban guerrilla movement in Uruguay in the 1960s and 70s that called themselves the Tupamaros. And of course there is the infamous Tupac Shakur, whose mother was a Black Panther and obviously inspired by the revolutionary group in Uruguay.