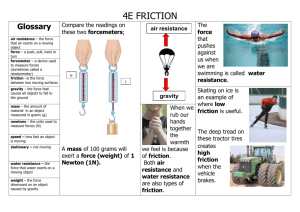

9. friction

advertisement

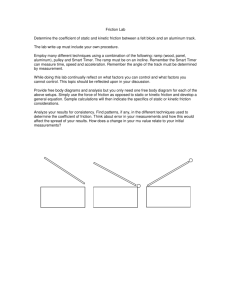

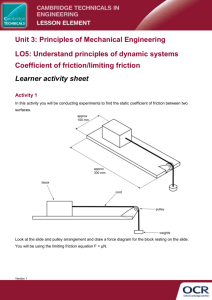

9. FRICTION 9.1 DRY FRICTION (Coulomb friction) The forces resulting from the contact of two plane surfaces can be expressed in terms of the normal force N and friction force f, or the magnitude R and angle of friction . If slip is impending, the magnitude of the maximum friction force is f s N s - coefficient of static friction (depends on the materials of the contacting surfaces and the conditions of the surfaces – Table 9.1) and its direction opposes the impending slip. The angle of friction equals the angle of static friction tan s s , or s arctan( s ) . The surfaces are not in relative motion. If the surfaces are sliding, the magnitude of the friction force is f k N k - coefficient of kinetic friction (generally, is smaller than that of s) and its direction opposes the relative motion. The angle of friction equals the angle of kinetic friction tan k k , or k arctan( k ) . 9.2 APPLICATIONS Effects of friction forces (wear, loss of energy, generation of heat) are often undesirable, but many devices cannot function properly without friction forces and may actually be designed to create them (e.g., car’s brakes and tires). THREADS - wood screws, machine screws - pitch – the axial distance p from one thread to the next slope – angle tan p 2r r – mean radius of the thread - the couple required for impending rotation and axial motion opposite to the direction of F is (Fig. 9.16b) M rF tan( s ) - the couple required for impending rotation and axial motion in the direction of F is (Fig. 9.17) M rF tan( s ) - replacing s with k in these expressions gives the couple necessary to rotate the shaft at a constant rate - if s = , the couple M is zero WEDGES - bifacial tools with the faces set at a small acute angle - when pushed forward, the faces exert large lateral forces as a result of the small angle between them; that large lateral force can be used to lift a load JOURNAL BEARINGS - supports designed to allow the supported object to move - the couple required for impending slip of the circular shaft is M rF sin s F – total load on the shaft - replacing s with k in this expression gives the couple necessary to rotate the shaft at a constant rate - this type of journal bearing is too primitive (the contacting surfaces of the shaft and bearing would quickly become worn), and designers usually incorporate “ball” or “roller” bearings to minimize friction BELT FRICTION - example: a rope wrapped through an angle around a fixed cylinder; a large force T2 exerted on one end can be supported by a relatively small force T1 applied to the other end (it is assumed that the tension T1 is known) - the maximum force T2 that can be applied without causing the rope to slip when the force on the other end is T1, is T2 T1e s is in radians - replacing s by k gives the force required to cause the rope to slide at a constant rate THRUST BEARINGS AND CLUTCHES - a thrust bearing supports a rotating shaft that is subjected to an axial load - example (Fig. 22): the conical end of the shaft is pressed against the mating conical cavity by an axial load; the couple necessary to rotate the shaft at a constant rate is 2 k F ro3 ri3 2 M 2 3 cos ro ri - a simpler thrust bearing: the bracket supports the flat end of a shaft of radius r that is subjected to an axial load F; the couple necessary to rotate the shaft at a constant rate is obtained by setting 0, ri 0 and ro r 2 M k Fr 3 - these bearings are good examples of the analysis of friction forces, but they would become worn too quickly, and designers usually minimize friction by incorporating “roller” bearings - a clutch is a device used to connect and disconnect two coaxial rotating shafts - example (Fig. 9.25): two disks of radius r attached to the ends of the shafts - when the clutch is engaged by pressing the disks together with axial forces F, the shafts can support a couple M due to the friction forces between the disks; the largest couple the clutch can support without slipping is 2 M s Fr 3