Blanchard4e_IM_Ch18

advertisement

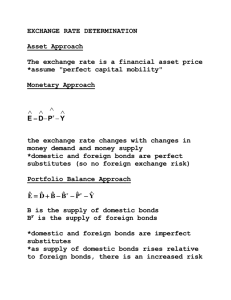

CHAPTER 18. OPENNESS IN GOODS AND FINANCIAL MARKETS I. MOTIVATING QUESTION How Does Openness Modify the Closed Economy, IS-LM, AD-AS Model? An open economy allows domestic residents to choose between home and foreign goods and between home and foreign assets. The first choice is governed by the relative price of foreign goods; the second by relative returns on foreign assets. II. WHY THE ANSWER MATTERS For countries other than the United States, open economy considerations have long had substantial effects on economic performance. In the United States, open economy issues are becoming increasingly important. This chapter describes the basic determinants of the trade balance and describes the implications of arbitrage between domestic and foreign bonds. Chapter 19 integrates the trade balance discussion into the closed economy goods market model (the Keynesian cross). Chapter 20 integrates the asset market discussion into the closed economy model of the money market, and develops an open economy IS-LM model. Chapter 21 discusses a medium run model of the open economy and considers exchange rate crises. III. KEY TOOLS, CONCEPTS, AND ASSUMPTIONS 1. Tools and Concepts i. The nominal exchange rate is the foreign currency price of domestic currency. The real exchange rate is the relative price of home goods to foreign goods. An increase in either of these variables is an appreciation from the perspective of the home country. ii. The balance of payments is a record of one country’s transactions with the rest of the world over a given period of time. The balance of payments consists of a current account, which records transactions in goods and services plus net international transfers plus net interest payments to individuals, and a capital account, which records transactions in assets. The chapter introduces basic balance of payments accounting and the balance of payments identity, which states that the current account and the capital account should sum to zero. iii. The uncovered interest parity condition equates the expected domestic currency returns on domestic and foreign bonds. Absent transactions costs and assuming that investors do not care about currency risk, investors will not be willing to hold both domestic and foreign bonds unless uncovered interest parity holds. 2. Assumptions i. The text assumes that domestic residents do not use foreign currency to purchase goods. This assumption is maintained throughout the formal work on the open economy. A footnote points out that U.S. dollars are often used for illegal transactions throughout the world and sometimes for legal transactions in economies with high inflation (or with a history of high inflation), but these phenomena are ignored in the formal work of the text. ii. The uncovered interest parity condition assumes that investors care only about expected returns and not about risk. This assumption is maintained throughout the formal discussion of the open economy. 85 IV. SUMMARY OF THE MATERIAL 1. Openness in Goods Markets Openness in goods markets means that domestic residents are able to buy foreign goods and sell domestic goods abroad. Goods sold to foreigners are called exports. Goods bought from foreigners are called imports. The difference between exports and imports is the trade balance. A negative trade balance is called a trade deficit, and a positive one a trade surplus. In the closed economy model developed earlier in the book, domestic residents made only one decision—how much to spend. In an open economy, domestic residents make two decisions—how much to spend and how much to spend on domestic (as opposed to foreign) goods. The latter decision depends on the real exchange rate, the relative price of foreign goods in terms of home goods. The real exchange rate depends on the nominal exchange rate (E), the home price level (P), and the foreign price level (P*). The nominal exchange rate is defined as the foreign currency price of home currency. So, for example, if the United States is the home country, and the price of one dollar is 100 yen, the nominal exchange rate is 100 yen/dollars. Given this definition, an increase in the exchange rate means that the home currency gains value (i.e., one unit of the home currency can buy more units of the foreign currency). Currency A depreciates vis-à-vis currency B if, after a change in the exchange rate, currency A will buy fewer units of currency B. Currency A appreciates vis-à-vis currency B if, after a change in the exchange rate, currency A will buy more units of currency B. Thus, an appreciation (depreciation) of the home currency means an increase (decrease) in E. Suppose the United States, the home country, produces only good, airplanes. If an airplane sells for P dollars, its price in yen is EP. Note that E has units of yen/dollar, and P has units of dollars/airplane, so EP has units of yen/airplane. Now assume that Japan, the foreign country, also produces only one good, cars. One could compare the yen price P* of cars produced in the Japan to the yen price of airplanes produced in the United States. This motivates the definition of the real exchange rate (): =EP/P*. (18.1) In this one-good-per-country example, the real exchange rate would have units of foreign goods per home good (in this case, cars per airplane). The nominal exchange rate has units of foreign currency per home currency. Since in fact there are many goods, in practice the real exchange rate is defined over baskets of goods, and P and P* refer to price indices. As such, the real exchange rate is also an index: its level is arbitrary (since one can choose any base year for the price indices), but its rate of change is well defined. In terms of price indices, the real exchange rate measures the price of a basket of goods in the home country in terms of baskets of goods in the home country. So, for example, if the real exchange rate is 2, the price of a home basket of goods is two foreign baskets of goods. Which basket depends upon which price index is used. If P refers to the GDP deflator, as in the text, then the real exchange rate measures the price of goods produced in the home country in terms of goods produced in the foreign country. An increase in the relative price of home goods is a real appreciation (an increase in ). An increase in the relative price of foreign goods is a real depreciation (a decrease in ). Since a country has many trading partners, the bilateral real exchange rate defined above is often replaced by a multilateral real exchange rate, which is a weighted average of the real exchange rate against each of the country’s trading partners. The weights are the shares of total home country trade with each country. 86 2. Openness in Financial Markets Openness in financial markets means that domestic residents are able to exchange assets (stocks, bonds, and money) with residents of other countries. There is a link between trade in assets and trade in goods. Trade in assets allows countries to borrow from one another. Thus, countries that run trade deficits can finance them by borrowing from countries that run trade surpluses.1 The balance of payments summarizes the transactions of one country with the rest of the world. It has two components. The first, the current account, is the sum of the trade balance, net investment income received from abroad, and transfers. As such, the current account is a record of net income received from the rest of the world. The second component of the balance of payments, the capital account, measures the purchase and sale of foreign assets. The capital account is defined as the net decrease in foreign assets (i.e., the increase in home assets held by foreigners minus the increase in foreign assets held by home country residents). Apart from a statistical discrepancy, the current account and the capital account sum to zero by construction. (The statistical discrepancy is often quite large even relative to the volume of exports and imports.) The intuition behind balance of payments accounting is simple. Think of a country as a single person. A country with a negative current account balance (a deficit) spends more than its income. To finance the deficit, it can either sell some of its existing assets to foreigners or borrow from foreigners (sell bonds to foreigners). By definition, these transactions have a positive sign in the capital account. Likewise, a country with a positive current account balance (a surplus) spends less than its income. It can dispose of the extra income by purchasing foreign assets or making loans to foreigners (buying foreign bonds). By definition, these transactions have a negative sign in the capital account. The capital account measures a country’s aggregate financial transactions with the rest of the world. Individual investment decisions are governed by the relative returns on home and foreign assets. The text assumes that domestic residents do not use foreign currency to purchase goods. Thus, there is no transactions motive for domestic residents to hold foreign currency. In addition, the text continues to assume that stocks and bonds are perfect substitutes, so it limits attention to home and foreign bonds. How does one choose between home and foreign bonds? Suppose a U.S. resident has a dollar to invest. Let i be the interest rate on U.S. bonds and i* the interest rate on Japanese bonds. Consider the choice between U.S. and Japanese bonds. Option 1: Buy U.S. bonds The return on one dollar equals 1+ it dollars. Option 2: Buy Japanese bonds. i. Exchange one dollar for Et yen. ii. Invest Et yen in Japanese bonds, with a return of (1+i*t)Et yen iii. Exchange (1+i*t)/Et yen for (1+i*t)Et/Et+1 dollars. The return on one dollar equals (1+i*t)Et/Et+1 dollars. The expected return on one dollar equals (1+i*t)Et/Eet+1 dollars. 1 Strictly, countries that run current account deficits borrow from countries that run current account surpluses. 87 Note that to transfer the return from the second option into dollars, the investor must exchange the return at the future period’s exchange rate Et+1, which is unknown at time t. The investor’s expectation of the future exchange rate is given by Eet+1. If investors care only about expected returns and not about risk, then they will choose the option with the higher expected return. If both U.S. and Japanese bonds are to be held by the private sector, it must be that the expected returns are the same under either option. In other words, 1+ i = (1+i*t)Et/Eet+1, which can be approximated by i≈i*t - (Eet+1-Et)/Et. (18.2) Equation (18.2) is called the uncovered interest parity condition. It is uncovered because an investor in foreign bonds is not protected from exchange rate risk. If the actual value of the exchange rate turns out to be lower than expected (i.e., the dollar is more valuable than expected), the investment in Japanese bonds produces a smaller return than the investment in U.S. bonds. In words, equation (18.2) says that the home interest rate equals (approximately) the foreign interest rate minus expected appreciation of the home currency. Expected appreciation of the home currency makes home assets more attractive, so investors are willing to hold them for less compensation (a smaller interest rate). 3. Conclusions and a Look Ahead Openness allows domestic residents two choices: the choice between home and foreign goods and the choice between home and foreign assets. Chapter 19 integrates the choice between home and foreign goods into the goods market equilibrium condition. Chapter 20 integrates the choice between home and foreign assets into the financial market equilibrium condition. Chapter 20 also combines goods and financial market equilibrium to analyze the short-run equilibrium of an open economy. Chapter 21 considers the medium run of an open economy and discusses exchange rate crises. V. PEDAGOGY The balance of payments is presented only in a rudimentary fashion in the text. The intuition that (apart from investment income and transfers) a trade deficit means that a country spends more than its income will be reinforced in Chapter 20, which presents the GDP identify for an open economy. It is worthwhile to emphasize this intuition more than the text does. As far as the mechanics of balance of payments accounting, it may help build intuition to imagine that all payments are made in terms of cash (in any given currency, say dollars). In this case, transactions in which the home country receives a cash payment get a positive sign in the balance of payments. Transactions in which the home country makes a cash payment get a negative sign. For example, the purchase by a U.S. resident of a Japanese car requires a cash payment to Japan. This gets a negative sign in the U.S. balance of payments. The purchase of a U.S. Treasury bond by a Japanese resident requires a cash payment to the United States. This transaction gets a positive sign in the balance of payments. 88 VI. EXTENSIONS 1. The Balance of Payments The text presents the balance of payments in the traditional manner, with a current and capital account. The U.S. presentation of the balance of payments has changed, however. Essentially, what was previously called the capital account is now called the financial account. In addition, a new category – called the capital account – has been created. The new capital account consists of a small set of asset movements that were previously recorded in the current account. The value of the items in the new capital account is typically very small for the United States. The text also omits several details of balance of payments accounting. An important one is that changes in official reserves are part of the financial account (which the text calls the capital account). Official reserves are foreign financial assets held by the central bank. For historical reasons, reserves include gold. An increase in reserves gets a negative sign in the financial account. Instructors may wish to explain how reserves fit into the balance of payments and to note that reserves affect the money supply. Doing so now helps prepare for a discussion of the central bank balance sheet in the context of fixed exchange rates (Chapter 20). 2. Uncovered Interest Parity Although uncovered interest parity is a foundation of open economy models, it has not been an empirical success. There are essentially two categories of explanation for this phenomenon. The first is that investors care about risk and there is a time-varying risk premium for any given exchange rate. The second is that investors make systematic forecast errors. Possibly forecast errors result from so-called Peso problems, i.e., large-cost, low probability events. If these events occur very rarely, then it will often turn out (ex post) that expectations based on these events are incorrect (although not irrational). Instructors may wish to point out how a risk premium on a currency increases the interest rate paid on bonds denominated in that currency. Unfortunately, little is known about how or why the risk premium changes over time. 3. The Foreign Exchange Market The text does not discuss alternative exchange rate regimes until Chapter 20. Instructors may wish to distinguish fixed and floating exchange rate regimes and to provide a brief history of the postwar transition from fixed to floating rates. Such a discussion fits naturally within the presentation of evidence on U.S. bilateral exchange rates in the postwar period. VII. OBSERVATIONS In Table 18-3, interest paid by the United States is less than interest received, despite the fact that the United States is a large net debtor. As it happened, the rate of return paid on U.S. assets held by foreigners in 2003 was much smaller than the rate of return paid on foreign assets held by U.S. residents. 89