Research Paper - Hannah Goldberg

advertisement

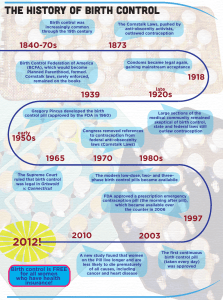

The Pill, Page 1 Hannah Goldberg, Megan Schrek, and Rita Gates Ms. A. Lockett English 015 August 10, 2011 A Woman's Liberation: The Birth Control Pill Taking oral contraceptives has recently become a daily routine for women across the globe. You may have heard of Yaz, Ortho-Novum, or Triphasil among it's many brand names. Most people today think of the birth control pill as nothing more than a drug to regulate hormones. However, the significance of the birth control pill is deeper than its prescribed function. This tiny pill has emerged as a technological object that carries enormous social, political, and cultural power. We will take you through a historical journey to show you how it redefined traditional gender-based roles, expanded the possible social roles a woman could have in society, and ultimately changed family lifestyles. Since ancient times, women have been seeking effective ways to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Ancient Greek and Roman scriptures describe practices of "using honey as a spermicidal barrier and jumping backwards seven times after intercourse" to prevent pregnancies (CQ). The picture to the right displays various sea sponges that were primitive compared to the modern contraceptives in use today. These sponges, soaked in vinegar, were thought to be effective spermicides (London 2). Years later, The Pill, Page 2 "the discovery of chewing gum, hair pins, needles, tallow candles and pencils lodged in female patients' urinary bladders," caused professionals to realize the serious effects of women being uneducated about their own reproductive health (Tone 491). Interestingly, historians have found evidence of birth control methods that were described in ancient scriptures. A list of some of the methods found were: “withdrawal by the male; melting suppositories designed to form an impenetrable coating over the cervix; diaphragms, caps, or other devices which are inserted into the vagina over the cervix and withdrawn after intercourse; intrauterine devices; douching after intercourse designed to kill or drive out the sperm; condoms; and varieties of the rhythm methods” (London 3). All of these methods are in use today, with the addition of the birth control pill. Douching was also very popular in ancient times, but not very effective. The most effective contraceptive device in use was a pessary. This was a vaginal suppository designed to block sperm from passing through the cervix or to kill it before entering. The ingredients used in the making of pessaries ranged from crocodile dung, to honey or sodium carbonate in the form of a gum-like material. The pessaries would melt at body temperature and create an impenetrable layer over the cervix. Most birth control methods were dangerous and did not offer high success rates. Coitus interruptus (the withdrawal or pull-out method), which is said to be one of the earliest birth control methods, was safe but still offered no guarantees that pregnancy would not occur (PBS Timeline 1). Abstinence became a woman’s only hope of confidently knowing that she would not become pregnant. The Pill, Page 3 It was of great importance to find an effective form of contraception in other countries, as well as in America, to control the size of families. Until recently, the French had relied solely on the withdrawal method to limit family size (McLaren 3). Their need for effective birth control was denied to them by those in power who thought the idea conflicted with social, moral, or religious doctrines. America was also slow to accept the idea of contraception. Anthony Comstock, a puritan born in 1844, felt the need to supervise the morality of the public. In 1873, the Comstock Act was passed which banned contraceptives and the distribution of information on any obscene or lascivious material. With the introduction of this new law, twenty four states quickly began their own mini Comstock Acts to reinforce these bans. Together, these laws prevented doctors from conducting research on effective contraceptives. Seeking a way to prevent unwanted pregnancies, women continued to practice unhealthy and ineffective methods of birth control into the 1900’s. Pregnancy, throughout the ages, was dangerous in itself. It was not uncommon for women to die during childbirth or to have severe complications during the nine months of pregnancy. The ability of women to perform their extensive household responsibilities was compromised by the physical effects of being pregnant. Women who already had children were burdened by the thought of having to care for yet another needy infant. Another child would also impact the family financially and take time away from caring for the husband, which caused even more distress for women. Margaret Sanger, an advocate of women’s rights, recognized these hardships endured by women. As a child, Sanger was aware that her mother suffered through eighteen pregnancies resulting in only eleven live births. She spent much her childhood caring for her younger siblings and being responsible for household chores. Later, as a nurse in the slums of the Lower East Side of New York City in 1912, Sanger was able to witness what happens to women who The Pill, Page 4 are pregnant with unwanted children. She observed the suffering caused by frequent childbirths and self-inflicted injuries. The turning point for Sanger came when she was called to Sadie Sachs’ apartment to assist the doctor after complications arising from a self-induced abortion. After begging for advice about ways to prevent future pregnancies, Sadie was told by the doctor that the only way was to practice abstinence. A few months later, Sanger was called back to the same apartment and was horrified to find Sadie dead from yet another self-induced abortion. Situations like Sadie’s were not uncommon during this time period. Sanger felt the responsibility to find a way to help these desperate women before they were driven to engage in unsafe abortions. She also realized that in order for women to be more equal in society and to have physically and mentally healthy lives, they needed to be able to decide when a pregnancy would be most convenient for themselves (Viney 34). She believed that women should have the freedom to fully enjoy sexual relations without being burdened by the fear of pregnancy. Sanger began to speak out for the need of women to be educated about birth control. In 1914 she began to publish a monthly newsletter called The Woman Rebel. This publication, which coined the term “birth control”, encouraged women to be in control of their bodies through the use of contraceptives. She also distributed suppositories and douches through the mail which led to her being charged for violating the Comstock Laws. She fled the country and learned many new and exciting discoveries about contraception while she was away. In 1915, while in Holland, Sanger visited a birth control clinic where she became convinced that diaphragms were a more effective method of birth control. She began to illegally smuggle diaphragms back into the United States with the help of her husband from whom she was then separated. It was very uncommon for a wife and husband to be separated in the early 1900’s. This even caused some reformers to turn against Sanger’s attempts to make contraceptives The Pill, Page 5 readily available. Another interesting fact regarding Sanger is that she was raised as a devout Roman Catholic. Typically, devout Catholics view the use of any form of contraception as a mortal sin. Evidently, Sanger’s belief in contraception and a women’s right to control her own body rose above her ingrained religious beliefs. She sacrificed most of her life to help women gain knowledge about their bodies and make birth control commonplace. In 1916, she opened America’s first family planning and birth control clinic in Brooklyn, New York. Nine days later she was arrested and went to prison for 30 days, but her actions triggered a court case which ruled that contraceptive devices could legally be promoted for the prevention and cure of disease. Finally, changes were being made. The Great Depression of 1929 triggered the demand for contraceptives to help limit the size of families during these economic hardships. Slowly, contraceptive industries began to arise even though, according to the Comstock Act, it was still illegal to manufacture, distribute, or sell contraceptive devices. The advertising industries took advantage of the new opportunities for sales by hiding the true use of their products through adopting the term “feminine hygiene”. Suppositories and douches were sold for the purpose of internal cleansing, instead of their true contraceptive uses. Tone also notes that sadly, women's magazines and advertising companies, The Pill, Page 6 "were conspicuously silent about the safety and efficacy of the products they tacitly endorsed" (Tone 493). Seen to the left is an advertisement from the 1930‘s that shows Lysol, a household cleaner, being advertised as a product for “feminine hygiene”. Unfortunately, government regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) could not prevent these companies from selling harmful products because their intended purposes were hidden by this false advertising. During this time, advertisements in women’s magazines primarily targeted females who were married because legally, only they were permitted to engage in sexual behavior. Advertisements such as the one to the right insinuated that women had the responsibility of finding a birth control method. However, if you look closely at the bottom right, to receive information on this particular contraceptive the consumer must fill in her date of marriage. Although this is a small part of the advertisement, it demonstrates that women were still considered to be the property of men because confirmation of a marriage was necessary to allow the woman to regulate her own body. By appealing to women’s fears, “[a]ds conveyed the message that ineffective contraception led not only to unwanted pregnancies, but also to illness, despair, and The Pill, Page 7 marital discord” (Tone 494). They preyed on a woman’s fear of losing her childhood, the burden of motherly responsibilities, and the dread of growing old. Women were made to feel solely responsible for any marital conflicts and the contraceptive companies took advantage of this to promote their products. Margaret Sanger did not give up at this point. Her efforts were beginning to make a difference on the laws surrounding contraception and a woman’s role in society, but she had still not found a convenient and effective method of birth control. At age 72, Sanger made a final effort to create the magic pill she had always envisioned. She joined forces with Gregory Pincus, a hormone researcher, who helped in the development of a progesterone pill to trick the body into thinking it is pregnant, thereby inhibiting ovulation. Katherine McCormick, a wealthy widow and good friend of Sanger’s, fully funded the research and development of this pill. Although there were still laws in place banning this research, they were able to carry out their work secretly. When it was time for FDA approval in 1954, they needed a physician to carry out a study involving humans. Dr. John Rock, already involved in progesterone studies, assisted in the first clinical trial which consisted of fifty women testing the newly invented pill. The results were astounding. One hundred percent of the women in the study showed no signs of ovulation during the twenty-one days of taking the pill (American Experience 4). The early formulation of the pill had some dangerous side effects, which were later minimized by incorporating estrogen with the progesterone and significantly lowering the dosage. The pill must be taken every day for twenty-one days followed by a seven day period (no pun intended) in which pills containing no hormones are ingested (UChicago 1). Sanger’s vision was made a reality. The Pill, Page 8 The pill was met with worldwide acceptance and by 1965, 6.5 million women were taking birth control pills. Doctors and professionals had joined the birth control movement in growing numbers around the 1930’s in order to decrease the injuries and deaths surrounding self-induced abortions. Others who joined this movement included those who supported women’s rights in general. Together, public supporters of the birth control movement helped to convince juries of the injustice of the Comstock Laws. Finally, in 1965, the Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut overturned the Comstock Act, ruling that the private use of contraceptives was a constitutional right (The Oyez Project 1). Without these obstacles, it was possible to gain public support and the financial resources necessary to market and distribute the newly found birth control enterprise (Shaffer 3). By 1967, 12.5 million women worldwide were taking the pill. Religious canons concerning birth control were being ignored. Contrary to church doctrine, two-thirds of all Catholic women were using contraceptives, 28% of whom were taking a birth control pill (American Experience 11). Women were finally taking control of their own lives. By finding a means to control the occurrence of pregnancies, women were ultimately able to break free from their traditional role as housewives. The pill entitled women to the freedom to decide their own future. It was possible for a woman to join the workforce without the encumbrance of an unexpected pregnancy. It also enabled couples to space out their children in a time frame that was more convenient for them. As Tone notes, birth control revealed a world in which “industry, gender and reproduction were frequently and intimately intertwined" (Tone 501). The Pill, Page 9 It is also important to mention the role that compulsory education played during Sanger’s lifetime. A woman's place was still in the home, without the right to vote or obtain a job in a patriarchal world that denied women their freedom. Compulsory education, which required all children (girls and boys) to attend school, became an effective law in every state by 1918. This was a significant step on the road toward female empowerment because it enabled women to gain the education necessary to enter the workforce. This, in combination with having a reliable form of contraception, enabled women to control their destiny. The vision of women and men being valued as equal citizens in society was on the horizon. The working woman not only transformed the female’s power, but also readdressed the role of the traditional man. During World War I and World War II, when men were sent to war, women were left to take over their jobs in the factories. Upon returning, the men were surprised to see that their positions both in the workforce and at home were redefined. He no longer was the sole breadwinner nor could he suppress his wife’s aspirations. Birth control enabled women to stay in the workforce as long as they desired. Shortly following, population control became a worldwide concern. In 1956, China’s leaders realized that the rapidly growing population could become a liability to economic growth, so mass birth control efforts were encouraged. By the early 1970’s, there was a recommended maximum of two children per family living in the city, and three to four per rural family. In 1978 the One-Child policy was put into effect for both rural and city families. The purpose was to help alleviate social, economic, and environmental problems in China. This could not have been possible without the invention of the birth control pill, as it was the safest, most effective method of birth control known at this time. “Thus a movement which began as an The Pill, Page 10 effort to rescue individual women from “biological slavery” has broadened into a global effort to promote social and political stability by limiting the number of children born” (Shaffer 1). Even today in the United States, birth control has assumed a legitimate place in society. Presently, under the Obama administration, health insurance plans must cover birth control as a preventative treatment for woman with no co-pays permitted. Women have also made their mark in the workforce as is demonstrated by the following additional aspects of this law to be covered without co-pays effective January 1, 2013: breast pumps for nursing mothers, an annual "well-woman" physical, screening for the virus that causes cervical cancer, and counseling on domestic violence (Alonso-Zaldivar). The emergence of the birth control pill as a viable method has been a slow process, but the work of Sanger has evidently made an impact on society. The birth control pill as a technological object has redefined gender-based roles through the expansion of women’s power in society. During a time when women's sexuality, contraceptives, and sexual intercourse were taboo, a passionate and persistent Sanger shed light on the controversial idea of contraceptives and aided in removing the stigma that society had placed upon the issue. Works Cited: 1. "American Experience | The Pill | Timeline." PBS: Public Broadcasting Service. Web. 26 July 2011. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/pill/timeline/timeline2.html>. 2. Tone, Andrea. "Contraceptive Consumers: Gender and the Political Economy of Birth Control in the 1930's." Journal of Social History. 3rd ed. Vol. 29. Peter N. Stearns, 1996. 485-506. Print. The Pill, Page 11 3. Clemmitt, Marcia. "Birth-Control Debate." CQ Researcher 24 June 2005: 565-88. Web. 1 Aug. 2011. http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre2005062400&type=hitlist &num=1 4. Battaglia, Mary Ann. "Margaret Sanger 1879-1966." New York City Women's Biography Hub. 14 Dec. 1998. Web. 6 Aug. 2011. <http://www.library.csi.cuny.edu/dept/history/lavender/386/msanger.html>. 5. "Birth Control Pill." University of Chicago Student Care Center, 2008. Web. 26 July 2011. <http://scc.uchicago.edu/pdf/library/birth_control_info.pdf>. 6. Glazer, Sarah. "Birth Control Choices." CQ Researcher 29 July 1994: 649-72. Web. 1 Aug. 2011. <http://library.cqpress.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrr e1994072900&type=hitlist&num=43> 7. Shaffer, Helen B. "Contraceptives and Society." Editorial Research Reports 1972. Vol. I. Washington: CQ Press, 1972. 415-38. CQ Researcher. Web. 1 Aug. 2011 <http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre1972060700&type=hitlist &num=6> 8. London, Kathleen. "82.06.03: The History of Birth Control." Yale University. Web. 01 Aug. 2011. <http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1982/6/82.06.03.x.html>. 9. Shaffer, Helen B. "Status of Birth Control." Editorial Research Reports 1958. Vol. II. Washington: CQ Press, 1958. 773-92. CQ Researcher. Web. 1 Aug. 2011. <http://library.cqpress.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrr e1958101500&type=hitlist&num=80> 10. "American Experience | The Pill | People & Events." PBS: Public Broadcasting Service. Web. 04 Aug. 2011. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/pill/peopleevents/e_comstock.html>. 11. Hopkins, Keith. "Contraception in the Roman Empire." Comparative Studies in Society and History. 1st ed. Vol. 8. Cambridge UP, 1965. 124-51. Print. The Pill, Page 12 12. "1963 Ad for Birth Control - Found in Mom's Basement." Advertising Is Good For You. Web. 02 Aug. 2011. <http://pzrservices.typepad.com/vintageadvertising/2008/08/1963-adfor-bir.html>. 13. Woody, William D., D. Brett King, and Wayne Viney. A History of Psychology. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Baco, 2003. Print. 14. McLaren, Angus. Abortion in France: Women and the Regulation of Family Size 1800-1914. 3rd ed. Vol. 10. Duke UP, 1978. 461-85. Print. 15. "Griswold v. Connecticut | The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law." The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law | U.S. Supreme Court Oral Argument Recordings, Case Abstracts and More. Web. 3 Aug. 2011. <http://www.oyez.org/cases/19601969/1964/1964_496>. 16. "Compulsory Education: Overview." NCSL Home. National Conference of State Legislatures. Web. 4 Aug. 2011. <http://www.ncsl.org/IssuesResearch/Education/CompulsoryEducationOverview/tabid/1294 3/Default.aspx>.