The Law is Not Blind

advertisement

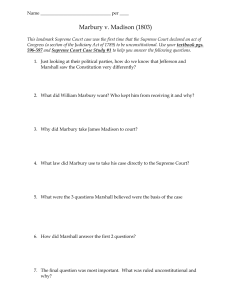

1 Patrick Context rules the Court. Politics ultimately prevail. The aura of sacredness that surrounds the Supreme Court is mere myth and while the 19th century American public tended to view the Court as a non-political institution, ruled by unbiased judges, its early history is one of response to social, political, regional and economic context. The law is not blind, nor is it deaf, as its vagueness has been given definition through decisions influenced by public opinion, political ideology and historical social need. The Supreme Court’s concept of law changes with the times, extending the scope of federal power during a perceived national crisis and upholding slavery when regionalism trumped reason.1 Supreme Court Justices have been overwhelming reactionary, overturning past decisions in landmark cases during both the Marshall and Taney eras of the Court, where the overall jurisprudence swung from a focus on federal power to state rights and then decisions were balanced between regional viewpoints. The very establishment of the Court as a legitimate branch of government was in itself one of the most politically strategic actions in American history. The Supreme Court responds to context because the institution understands its own vulnerability. With no constitutionally granted power of judicial review and a power that was only established as a result of the institution’s own political beginnings, the Court’s legitimacy depended on the American people’s willingness to uphold its decisions and opinions.2 Understanding its own vulnerability, the Court acknowledged that while it may not be checked by another branch of government, its power is accompanied by a check through civic opinion. For this reason, the Supreme Court is an institution that responds to political, social, 1 The Oyez Project, Dred Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1851-1900/1856/1856_0). 2 Milestone Documents in the National Archives [Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1995] 23-24. 2 economic, and regional context. Responding to societal needs and public opinion and interrupting law with regard to context has shaped the history of the Supreme Court, specifically its beginnings in the 19th century. This essay will demonstrate the political nature of the early Supreme Court by addressing its responses to context during its establishment, contract law debates and issues of slavery brought before it and during the Marshall and Taney Courts. The Supreme Court’s first response to context and its vulnerability to political power will be noted through Chief Justice John Marshall’s giving the institution its legitimacy in Marbury v. Madison (1803), a “case [which] establishes the Supreme Court's power of judicial review.”3 This discussion will present the Court’s path to legitimacy by highlighting its early years as a fluid and inferior branch of government that may not have continued to exist where it not for the shrewd establishment of judicial review. The Taney Court will then be presented as a reaction to the Marshall era. Again, the reactionary nature of the supposedly neutral justices will be highlighted. Comparing the Marshall and Taney Courts will exemplify the political influence and notion of judicial vulnerability that existed throughout the history of the Supreme Court having its roots in the institution’s 19th century beginnings. Political influence’s shaping Court opinion will be noted in highlighting the case Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837) as a reaction to the Marshall Court’s unyielding support of nationalism, as perpetuated by his own Federalist Party. The Taney era will also demonstrate how the Supreme Court upholds and responds to public opinion 3 The Oyez Project, Marbury v. Madison , 5 U.S. 137 (1803) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1803/1803_0). 3 through an examination of its Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) opinion. A decision which will also identity how the Court’s justices were not immune to the regional conflicts that lead up the Civil War. In modern times, “Americans' approval of the Supreme Court” has, on average, always hovered a little higher than “60%.”4 A clear majority consider the Court neutral and, therefore, the most powerful of the three branches of federal government. Many Americans, however, do not understand that the Supreme Court began powerless: blind, deaf, and dumb. Led by its first Chief Justice, John Jay, the institution was composed of only six judges, who would often ride to lower circuits throughout their terms as justices.5 Membership on the Court was very fluid, having three Chief Justices between the years 1789 and 1801 and the institution did not acquire its own building until 1935.67 Put simply, the Supreme Court maintained the scope of power of the current English Monarch, having majesty with no true influence on the magistrate. In fact, the Court even lacked a building and “many scholars cite the absence of a separate Supreme Court building as evidence that the early Court lacked prestige" let alone influence.8 In 1803, the Supreme Court became a legitimate institution during the case Marbury v. Madison, and through Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion, the Court became a branch of government that was neither blind, nor deaf, nor dumb. A branch of the federal government Carrol, Joseph. “1/3 of Americans Say U.S. Supreme Court is ‘Too Conservative: Plurality Still says Court’s Balance Between Liberal and Conservative is ‘about right’”. Gallup (2007) available at: (http://www.gallup.com/poll/28861/onethird-americans-say-us-supreme-court-too-conservative.aspx). 5 The Supreme Court, Part I: The Least Dangerous Branch. Prod. by Rob Rapley, Julia Elliot, and Jamila Wignot. HiddenHill Productions and Thirteen/wnet New York, 2006. 60 mins. (http://www.historyofsupremecourt.org/). 6 "A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. http://www.supremecourt.gov/about/briefoverview.pdf. 7 The Supreme Court, Part I: The Least Dangerous Branch. Prod. by Rob Rapley, Julia Elliot, and Jamila Wignot. 8 Scott Douglas Gerber (editor) (1998). "Seriatim: The Supreme Court Before John Marshall". New York University Press. (83-85). 4 4 which gave itself the power to declare actions on behalf of the other branches unconstitutional through use of its newly created concept of judicial review. It is important to understand that Marbury v. Madison (1803) and its establishment of judicial review demonstrate that the Court’s power rose out of context and that John Marshall’s majority opinion was largely a political tactic. At its core, Marbury v. Madison (1803) centered on a political dispute between federalists or nationalists, “who argued that a strong central government was essential to the unity of the new nation” and dual-federalists, as represented by the Jeffersonians, who “viewed the United States more as a confederation of sovereign entities woven together by a common interest.”9 These two political parties vehemently battled over how a new nation should be constructed and this battle permeated into the Supreme Court. Upon the election of Jefferson to the presidency, his predecessor John Adams attempted to stack the judiciary at various levels with loyal defenders of the Federalist Party. Due to various circumstances, not all commissions or notes that inform a candidate of his or her selection, were delivered to their respective judicial appointees before Jefferson was sworn in as the 3rd president of the United States. A believer in dual-federalism, “which favored states' rights and a strict interpretation of the Constitution,” Jefferson did not seek to seat any judicial appointments made by his rival Federalist Party, who had not received their commissions.10 This action left several men without a judgeship and one man, Marbury, asked the Secretary of State, James Madison, whose job it was to instate potential justices, to deliver his commission, so that he would be established as a justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. Madison, under the influence of his state’s rights focused dual-federalist president, refused to give Marbury his 9 Cunningham, Noble E., 1963. The Jeffersonian Republicans in Power: Party Operations, 1801–1809. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Univ. of North Carolina Press. (162-165). 10 Cunningham, Noble E., 1963. The Jeffersonian Republicans in Power: Party Operations, 1801–1809 5 commission. Marbury, in turn, brought suit against Madison and eventually this dispute reached the Supreme Court, where Marbury insisted the Court issue a writ of mandamus, effectively forcing Madison to instate him as a Justice of the Peace.11 Marbury justified the Court’s issuing him a writ of mandamus under Section Thirteen of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which stated “The Supreme Court shall . . . have power to issue writs of prohibition to the district courts ... and writs of mandamus ... to any courts appointed, or persons holding office, under the authority of the United States.”12 When the case reached the Supreme Court, John Marshall wrote the 6-0 majority opinion and stated “the authority given to the Supreme Court by the act establishing the judicial system of the United States to issue writs of mandamus to public officers appears not to be warranted by the Constitution.”13 In other words, Marshall declared that it was not within the power of the judiciary to issue writs of mandamus and in doing so effectively defined Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutional. Though Marbury did not become a justice of the peace, the major importance of this case lies in the fact that the Supreme Court, for the first time, had struck down an act of Congress. Marshall then furthered and cemented the Court’s newfound power in stating, “those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret the rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Court must decide on the operation of each” and thereby established the institution’s power of judicial review. 14 Gone were the days of Chief Justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth when the Court’s biggest decision was seen in 11 The Oyez Project, Marbury v. Madison. Judiciary Act of 1789, § 13. 13 Marbury v. Madison, 5 U. S. 137 (1803). 14 Marbury v. Madison, 5 U. S. 137 (1803). 12 6 West v. Barnes (1791) “a case involving a procedural issue.”15 After Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison (1803) the Supreme Court was not only a legitimate federal government, the institution became the most powerful branch of government, its justices having the ability to hold office for life “during good Behaviour” their only check being confirmed by the United States Senate. 16 Marshall’s majority opinion responded to the context of a political batter between nationalists and dual-federalists that made its way into the Court. Due to the politics behind Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Supreme Court faced the possibility of becoming illegitimate on two different fronts. A federalist, John Marshall faced a political battle with President Jefferson, a dual-federalist. If the Court findings dismissed Marbury’s right to become a justice of the peace and did not allow him to be commissioned, Marshall faced the almost certain political ramification of Jefferson ignoring his request to have Madison issue Marbury a commission to be established a justice of the peace.17 This potential political fall-out would have stripped the Supreme Court of the little influence it had in 1803. Additionally, Marshall and his Court faced a potential political upheaval from the Federalist Party – Federalist John Adams appointed Marshall Chief Justice - if he it did not grant Marbury’s right to become a justice of the peace.18 The pending decision presented a potential no win situation for the Supreme Court: become illegitimate or endure a political civil war with 15 Scott Douglas Gerber (editor) (1998). "Seriatim: The Supreme Court Before John Marshall". U.S. Constitution. 17 The Supreme Court, Part I: The Least Dangerous Branch. Prod. by Rob Rapley, Julia Elliot, and Jamila Wignot. 18 "A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. http://www.supremecourt.gov/about/briefoverview.pdf. 16 7 one’s own party. The supposedly blind justices had seen the light, a light which shone the true character of the Court and its proceedings as both political and contextual. A shrewd political who was not blinded by the law, Marshall was able to appease both sides, while subtly asserting his Court’s power. In a 6-0 decision, the Court sided in Marbury’s favor stating, “having this legal title to the office, he has a consequent right to the commission, a refusal to deliver which is a plain violation of that right, for which the laws of his country afford him a remedy.”19 Additionally, Marshall’s opinion appeased the Federalists, by means of scolding Jefferson and Madison by stating, “to withhold the commission, therefore, is an act deemed by the Court not warranted by law, but violative of a vested legal right,” essentially declaring that the actions by the Jeffersonian administration were unlawful.20 In this sense, Marshall towed his party’s line, publicly deeming the actions of Jefferson’s administration wrong and acknowledging Marbury’s just right to have received his commission. Through use of the same opinion, Marshall placed Jefferson in a situation where he had to accept the Court’s findings that his party acted wrongfully and, at the same time, acknowledge the institution’s newfound right to judicial review. Specifically, since Marbury, a Federalist, was not made a justice of the peace, Jefferson, a dual-federalist, could not go against the Court, as he had to uphold his political own views. Many Jeffersonians saw this decision as a major political victory and to go against it would have been politically unwise.21 Ending his opinion with the words, “that a law repugnant to the Constitution is void, and that courts, as well as other departments, are bound by that instrument the rule must be discharged,” the Court denied 19 Marbury v. Madison, 5 U. S. 137 (1803). Marbury v. Madison, 5 U. S. 137 (1803). 21 The Oyez Project, Marbury v. Madison. 20 8 Marbury his request.22 Moreover, “in denying his request, the Court held that it lacked jurisdiction because Section 13 of the Judiciary Act passed by Congress in 1789, which authorized the Court to issue such a writ, was unconstitutional and thus invalid" and through this declaration, judicial review was established.23 Jefferson had no choice but to accept the opinion. He had been politically outwitted by a supposedly neutral Court. Marbury v. Madison (1803) demonstrates that context, particularly political context, created Court concreteness. Perhaps more demonstrative of the early Supreme Court’s being political and reacting to social context than the Marshall Court’s establishment of judicial review, is the fact the Supreme Court did not use judicial review against the federal government for the remainder of Marshall’s term. This is because the Court understood that its power was dependant on the other two branches of government’s and the people’s upholding its decisions. During a time a national polarization it would have been unwise to continuously use the self-appointed power of review because, while judicial review had been established, the decisions of the Supreme Court could still be ignored, as no constitutional right grantees the Court’s ability to enforce its decisions.24 (An example of a branch of government’s ignoring a Supreme Court decision was President Andrew Jackson’s choice not to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia (1832)).25 The Court acknowledged its own vulnerability during the context of 19th century America. 22 Marbury v. Madison, 5 U. S. 137 (1803). Marbury v. Madison. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. 24 U.S. Constitution. 25 The Oyez Project, Worcester v. Georgia , 31 U.S. 515 (1832) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1832/1832_2). 23 9 Understanding context and acting out of its own political preferences, the Marshall Court’s refusal to use judicial review on a number of cases, actually advanced the nationalist agenda by expanding the power of the federal government. An example of the Court’s upholding questionable acts of Congress to expand national power is its decision in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). The case centered on two main questions “did Congress have the authority to establish a national bank within a state and did the Maryland law [which enforced a tax on the national bank] unconstitutionally interfere with congressional powers.”26 At its core, McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) was representative of an ongoing struggle in 19th century America between dual-federalists or those who favored state’s rights and federalists who sought to expand national power. In a unanimous decision, “the Court held that Congress had the power to incorporate the bank and that Maryland could not tax instruments of the national government employed in the execution of constitutional powers.”27 Already a blow to supporters of state’s rights over national power, the opinion of the court written by Marshall furthered the powers of the national government in stating, “this Government is acknowledged by all to be one of enumerated powers.”28 By enumerated powers, Marshall meant powers that “were not explicitly outlined in the Constitution,” essentially creating federal government rights through a court decision.29 Additionally, Marshall’s opinion stated that while the states retained the power of taxation, "the constitution and the laws made in pursuance thereof are supreme. . .they control the constitution 26 The Oyez Project, McCulloch v. Maryland , 17 U.S. 316 (1819) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1819/1819_0). 27 The Oyez Project, McCulloch v. Maryland , 17 U.S. 316 (1819). 28 McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U. S. 316 (1819). 29 The Oyez Project, McCulloch v. Maryland , 17 U.S. 316 (1819). 10 and laws of the respective states, and cannot be controlled by them."30 In this statement, the Court affirmed that national power trumped state power. A political debate was now settled. Federal power’s being supreme was made the law of the land. While the Marshall Court did not use the power of judicial review against the federal government after Marbury v. Madison (1803), it did not hesitate to use its power against the states. Perhaps, influenced by personal nationalist preference, developed during his service in the Revolutionary War, Marshall expanded national government power by using judicial review against the states in the cases Fletcher v. Peck (1810) and Cohens v. Virginia (1821).31 In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), the Court unanimously declared that Georgia’s new “laws annulling contracts or grants made by previous legislative acts were constitutionally impermissible” and Marshall did not even attempt to hide his distaste for the Georgia state legislature labeling Fletcher v. Peck (1810) “a mere feigned case.”32 In another unanimous decision, the Marshall Court found that the Supreme Court had the power to review any state’s criminal proceedings in Cohens v. Virginia. Marshall’s opinion furthered federal power and the Supreme Court’s own influence over the states, declaring that when state laws and constitutions, where repugnant to the Constitution and federal laws, they were "absolutely void."33 For the third time, the Marshall Court declared federal power to be triumphant over state’s rights. Overall, the Marshall Court was heavily influenced by political context. Each of its four most political decisions, all having a question of federal versus state power at its core, were decided in favor of federal power in unanimous decisions. This should be an unsurprising fact as 30 McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U. S. 316 (1819). The Supreme Court, Part I: The Least Dangerous Branch. Prod. by Rob Rapley, Julia Elliot, and Jamila Wignot. 32 Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U. S. 87 (1810). 33 Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264 (1821). 31 11 the justices were appointed by federalist presidents. Additionally, the Marshall Court understood the vulnerability of its power of judicial review and took careful measures to expand federal power, while not threatening its own legitimacy. It decisions exemplify that the beginnings of the supposedly neutral Supreme Court, had a foundation in response to political context. John Marshall recognized the Constitution did not grant the Supreme Court the power of judicial review. Therefore, he only used judicial review against the national government once; realizing his and the Court’s legitimacy relied on the Executive Branch’s carrying out its decisions. The notion of the Court’s being vulnerable was not lost on Marshall’s successor, Chief Justice Roger Taney. Neither was the notion of the Supreme Court’s being an institution permeated by politics which made decisions based on a changing cultural context. The Marshall Court was one that promoted nationalism. The Taney Era was a response to nationalism and, later, public opinion. Less than eight years before Taney became Chief Justice, Andrew Jackson was elected president of the United States. Unlike the president’s who appointed most of the justices to the Marshall Court, Jackson was a supporter of state’s rights and as president he sought to make the Court his own.34 During his presidency, Jackson appointed six justices to the Court, all supporters of state power.35 Jackson did not consider the Supreme Court the final arbiter of law and intended to illuminate the institution’s vulnerability for his own political gain. This was apparent in the aftermath of Worcester v. Georgia (1832), a case which considered whether states could regulate the areas Native Americans could live in. The Supreme Court, still under the leadership of Marshall, stated, "the Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community occupying 34 35 Scott Gerber, The Journal of American History 93, no. 3: 5. The Supreme Court, Part I: The Least Dangerous Branch. Prod. by Rob Rapley, Julia Elliot, and Jamila Wignot. 12 its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no force. The whole intercourse between the United States and this nation, is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States."36 This essentially declared the state of Georgia was acting unconstitutionally, and charged President Jackson with intervening. Jackson, however, refused to carry out the ruling of the Supreme Court, declining to intervene when Georgia defied a Court ruling which gave protection to Native Americans.37 The line between federalists, now known as Whigs, and state’s rights supporters, know belonging to the Democratic Party, became bolder and Jackson became determined to enforce the state’s rights agenda by means of the very institution that lessened it, the Supreme Court. The Jackson Presidency greatly shaped the Taney Court. Specifically, Jackson’s influence upon the Court created a context of a need for state powers that were not recognized during the Marshall era and Jackson’s power over the Court was largely realized through his ability to appoint six justices to it.38 The Taney Court’s responding to Marshall era nationalism is best noted in the case Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837). The case centered on a state legislature, Massachusetts, breaking a contract with the Charles River Bridge Company to allow for the building of the Warren Bridge by another state contracted company: recall that in Fletcher v. Peck (1810), the Supreme Court stated that state legislatures could not void established contracts through means of new legislation. 39 40 The new state contract with the Warren Bridge Company stated that after six years, traffic across the bridge would be free of 36 Worcestor v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832). The Oyez Project, Worcester v. Georgia , 31 U.S. 515 (1832) 38 McCloskey and Levinson, The American Supreme Court( Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 294. 37 39 40 Epstein and Walker. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: A Short Course, 4th Ed, 166-174. Epstein and Walker. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: A Short Course, 4th Ed, 166-174. 13 tolls.41 The Warren Bridge was in close proximity to the Charles Bridge and since the Warren Bridge did not have to rely on tolls to sustain itself, the Charles Bridge was in grave danger of being put out of business.42 The Charles River Bridge Company sued the state on the grounds it had unconstitutionally broke a contract and when the case reached the Supreme Court, Taney and the justices broke the precedent set in Fletcher v. Peck (1810) that a state legislature could not void established contracts by means of new legislation.43 Through his majority opinion, Chief Justice Taney gave the state’s more power than the Supreme Court had previously granted in stating, "while the rights of private property are sacredly guarded, we must not forget that the community also have rights, and that the happiness and well-being of every citizen depends on their faithful preservation."44 Through the Court’s opinion, Charles River Bridge established states as having the right to police powers, under the 10th Amendment, to advance the health, safety, and well-being of its citizens.45 While this case did not officially overturn Fletcher v. Peck (1810) the Jackson influence on the Court created a new standard for state power that was protected under the 10th Amendment.46 Moreover, Jackson’s political influence upon the Court in this decision cannot be denied, as he appointed all five of the justices who voted with the majority, in favor of expanded state’s rights, Baldwin, 41 Epstein and Walker. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: A Short Course, 4th Ed, 166-174. Epstein and Walker. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: A Short Course, 4th Ed, 166-174. 43 Epstein and Walker. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: A Short Course, 4th Ed, 166-174. 44 Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 36 U.S. 420 (1837). 45 McCloskey and Levinson, The American Supreme Court, 302, 304 46 McCloskey and Levinson, The American Supreme Court, 302, 304. 42 14 Barbor, McLean, Taney, and Wayne.47 This was the first instance of a change in jurisprudence due to political context causing a reversal in ruling for the Supreme Court. The Taney Court also represented the Court’s first response to public opinion concerning social issues. This is bested noted in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857). In Dred Scott, the Supreme Court used the power of judicial review to strike down an act of the federal government for only the second time in its history. In its decision, the Taney Court upheld state’s rights to slavery, stating the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, as “no State can, by any act or law of its own, passed since the adoption of the Constitution, introduce a new member into the political community created by the Constitution of the United States.”48 In a 7-2 decision, the Court also upheld the notion that a slave was considered “property.”49 Considered to be one of the worst Court rulings in history, the Dred Scott decision demonstrates the Court’s having been aligned with public opinion. Specifically, slavery was still considered to be both acceptable and relevant at the time Dred Scott was decided, especially in the south.50 It was an institution that benefited the country economically and if the Taney Court had struck down slavery as unconstitutional, public outcry and refusal to enforce its ruling, especially in the south, would have threatened the Court’s legitimacy. The Dred Scott decision also demonstrates the affect regional and party loyalties had upon the Supreme Court in the era leading up to the Civil War. Both Justice Curtis and Justice 47 48 McCloskey and Levinson, The American Supreme Court, 302, 304. Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U. S. 393 (1856). Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U. S. 393 (1856). 50 McCloskey and Levinson, The American Supreme Court, 375-378. 49 15 McLean, the two dissenters, were from Union States, Massachusetts and New Jersey respectively.51 It is likely their regional loyalties influenced their decision. Additionally, five of the justices who voted in favor of Dred Scott, hailed from Confederate States which vastly supported slavery, while the two from Union States who voted with the majority are described as “loyal Jacksonian Democrats.”5253 As with every major Supreme Court decision of the 19th century, Dred Scott was made out of context. Political loyalties and regional upbringings both played a major role in the final decision. A decision that ultimately upheld public opinion. The law is not blind, nor is it deaf, or dumb. The Supreme Court sees, hears, and feels the political, economic, and social context that surrounds it. Context ruled the 19th century Supreme Court, as opinions were shaped by forces existing beyond the sacred veil of its justices. The Supreme Court responded to public opinion and societal need because it understood its own vulnerability. With no constitutionally granted right of judicial review, the Court must rely on the other two branches of government, the states and the people to enforce its opinions. Understanding this, the Supreme Court has never strayed too far from the mainstream opinion of the day and its justices have remained loyal to those who put them in the highest court in the land. The 19th century Court set this precedent, a precedent that has not been overturned. 51 The Oyez Project, Dred Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1851-1900/1856/1856_0). 52 The Oyez Project, Dred Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857). 53 The Oyez Project, Dred Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857). 16 BIBLIOGRAPHY "A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. http://www.supremecourt.gov/about/briefoverview.pdf. Carrol, Joseph. “1/3 of Americans Say U.S. Supreme Court is ‘Too Conservative: Plurality Still says Court’s Balance Between Liberal and Conservative is ‘about right’”. Gallup (2007) available at: (http://www.gallup.com/poll/28861/onethird-americans-say-us-supremecourt-too-conservative.aspx). Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 36 U.S. 420 (1837). Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264 (1821). Cunningham, Noble E., 1963. The Jeffersonian Republicans in Power: Party Operations, 1801– 1809. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 162-165. Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U. S. 393 (1856). Epstein and Walker. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: A Short Course, 4th Ed, 166174. Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U. S. 87 (1810). Judiciary Act of 1789, § 13. Marbury v. Madison, 5 U. S. 137 (1803). Marbury v. Madison. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Milestone Documents in the National Archives [Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1995] pp. 23-24. McCloskey and Levinson, The American Supreme Court( Chicago, Illinois: University of 17 Chicago Press, 2009), 294, 302,304, 375-378. McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U. S. 316 (1819). Scott Gerber, The Journal of American History 93, no. 3: 5. Scott Douglas Gerber (editor) (1998). "Seriatim: The Supreme Court Before John Marshall". New York University Press, 83-85. The Oyez Project, Dred Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1851-1900/1856/1856_0). The Oyez Project, Marbury v. Madison , 5 U.S. 137 (1803) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1803/1803_0). The Oyez Project, McCulloch v. Maryland , 17 U.S. 316 (1819) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1819/1819_0). The Oyez Project, Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832) available at: (http://oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1832/1832_2). The Supreme Court, Part I: The Least Dangerous Branch. Prod. by Rob Rapley, Julia Elliot, and Jamila Wignot. HiddenHill Productions and Thirteen/wnet New York, 2006. 60 mins. (http://www.historyofsupremecourt.org/). U.S. Constitution. Worcestor v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832). 18