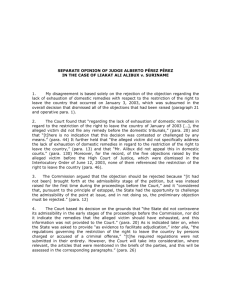

The Commission's arguments - Corte Interamericana de Derechos

advertisement