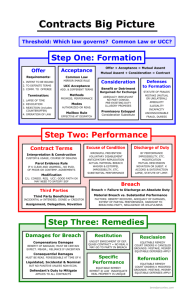

In Contracts, the prima facie case of breach of contract

advertisement