Brizee, Allen

advertisement

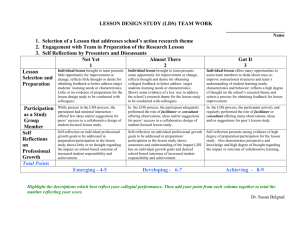

Retrieved March, 14, 2007, from: http://athena.english.vt.edu/~owl/wcip/learningdisabilities.htm Brizee, Allen. "Handbook for Tutoring Students with Learning Disabilities." Spring 1998. PLEASE NOTE: This article was submitted as part of the Writing Center Internship course. This course is offered to undergraduate students and is designed to introduce students to the techniques and art of tutoring writing. The course meets all semester long and discusses current writing center scholarship, and the interns get a chance to try out their own skills. The course culminates in a research project of some sort by each intern. The author(s) has(have) given us permission to post his/her(their) material here. Editorial changes may have been made to facilitate the presentation of the material in the online environment. If you have any questions about this, feel free to contact us here. Return to Index of Intern Projects Handbook for Tutoring Students with Learning Disabilities Allen Brizee Writing Center, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Virginia Tech 1998 Table of Contents I. Introduction Why the Writing Center Needs Information on Learning Disabilities Goals of This Handbook What Are Learning Disabilities? Misconceptions I What Learning Disabilities Are Not General Suggestions for Tutoring Students with Learning Disabilities II. How to Read the Signs: Recognizing Global Writing Problems Short-Term Solutions for Global Writing Problems Clearly Presenting and Supporting Main Ideas or Theses Traditional Outlines Non-Systematic Outlines Long-Term Solutions for Global Writing Problems Daily Journals POWER Plan III. How to Read the Signs: Recognizing Grammar Problems Short-Term Solutions to Grammar Problems Recognizing and Correcting Grammar Errors Strategies for Improving Spelling, Capitalization, Punctuation, Proofreading Word Processing Programs Essential Tools DISSECT Method Personal Spelling Books Word Isolation Memory and Association Techniques Dictionaries Proofreading Punctuation Sentence Isolation Mnemonics Long-Term Solutions for Grammar Problems Daily Journals Color Highlighting COPS Method A Word on Style Reading Varying Sentence Patterns IV. Conclusion V. Works Cited VI. Works Consulted VII. Appendix: A Listing of Organizations and Associations Established to Assist the Learning Disabled I. Introduction Why the Writing Center Needs Information on Learning Disabilities (LDs) Imagine trying to learn a foreign language while unable to read the text because of tiny neurological misfires in your optic muscles. Imagine trying to read this foreign language when d's, b's, p's, h's, and w's appear scrambled and mixed up. Imagine dow barht bat mould de (imagine how hard that would be). Learning languages is difficult enough without these kinds of shortcomings, yet students with learning disabilities overcome these kinds of problems everyday when they read a book, when they take notes in class, 6r when they write a paper. To many English speaking students with LDs, aspects of their native tongue seem as foreign and as difficult as learning another language. Yet an increasing amount of LD students attend college despite their difficulty with learning. The number of students with LDs entering postsecondary programs increases yearly. This growing trend necessitates a higher understanding of the unique needs students with LDs may require to excel in a college environment. Ml too often, LDs are regarded as childhood developmental problems that can be "cured" by intervention in elementary and high school. This is not the case, however. It is now clear that people with learning disabilities will have difficulty acquiring, processing, and producing information their entire lives (Wong 15). Given this, educators are obliged to assist students enrolled in college overcome LDs so that patterns of success are achieved. These patterns of success can only be attained by increasing awareness of adult LDs, and by training educators in effective techniques designed for college level students. Tutors need to be aware of the increasing population of disabled students that may turn to the Writing Center for help. Tutors also need to be aware of proven strategies for tackling these challenges. The Writing Center's ability to assist LD clients will become one facet of the program designed to assist students with disabilities at Virginia Tech. Goals of This Project This information packet is designed to improve writing instruction in Virginia Tech's Writing Center by increasing tutors' awareness of LDs. It is designed to provide constructive strategies for teaching composition to students with LDs. The goals of this booklet are as follows: Describe what constitutes LDs Dismiss misconceptions that could hamper the instruction of students with LDs in the Writing Center Educate tutors in methods of recognizing the signs of possible LDs in works of composition Examine different types of errors most experienced by students with LDs Explore strategies for tackling these problems. Since Writing Center tutors commonly have only a short period of time to work with students, short-term strategies are outlined first so that tutors can work within these time restraints to provide high level instruction. However, some tutors develop clientele that return for multiple sessions, so long-term strategies are also described to help these tutors develop more complex, and generally more successful methods of teaching. This handbook does not describe different types of LDs. Mso, this booklet does not recommend diagnosing LDs while working in the Writing Center. The Writing Center is not designed for psychological analysis; tutors are not trained to pinpoint subtle neurological processes. Diagnosis is simply not our job. We are trained to teach composition and methods of improving the writing process. For detailed analysis of instruction designed specifically for different types of LDs, please refer to the Works Cited, Works Referenced, and Appendix. Fearing discrimination, some students may be reluctant to reveal their learning difficulty. Being aware of possible LDs improves our approach to clients who may not have continued LD support after high school. Awareness of effective strategies allows tutors to improve instruction for students who have diagnosed LDs, and for those who, for whatever reason, are not engaged in adult LD education. Students come to the Writing Center for help. It is our obligation to remain educated about the diverse challenges facing writing tutors at Virginia Tech, that is the primary goal of this project. Working in tandem with the Students with Disabilities Association, and the Dean of Students Office (Services for Students with Disabilities), the Writing Center can provide quality writing tutelage for clients with LDs. This handbook strives to expand the understanding of LDs as they affect clients using our facilities. This handbook strives to ensure quality instruction for students with LDs in the Virginia Tech Writing Center. What Are Learning Disabilities? The most recent definition from the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities ~JCLD) states that an LD is "a lifelong condition that continues to affect the manner in which individuals take in information and retain and express the knowledge and understanding they possess. The most common deficits in adults with LDs are in reading rate, spelling, and mechanics in writing..." (Vogel/Adelman 4). The most important fact to remember is that students with LDs are just as intelligent as their nonLD peers. Regardless of causes and categories experts find for LDs, scientists resoundingly agree that students with LDs merely process information differently than do students without LDs (Wong 3-4). LDs affect the formula by which students receive, process, and produce information. It is not the inherent intelligence that influences output, rather, it is the manner in which information is processed that affects the output of these students. These processes influence several areas of students' lives. Generally, LDs are separated into two categories, non-academic and academic, which can be divided into a myriad of subcategorizes. Psychologists, neurologists, and educators debate specific names and causes for LDs. Regardless of this debate, the symptoms for these LDs are universally recognized. The following diagram, borrowed from Bernice Wong's The ABCs of Learning Disabilities, shows the structures of LDs: Figure 1 Learning disabilities as an umbrella term for various academic and non-academic learning disabibties. Regardless of the name of the LD (dyslexia, ADDHD, aphasia or paraphasia), whether the disability is neurological or environmental, students with LDs exhibit symptoms falling into the above categories, "Mthough LDs can impair the entire spectrum of abilities... the academic arena is the primary concern of college level students with LDs. This arena includes... writing, and composition" (Mangrum 14). Mthough non-academic symptoms certainly affect academic output, this booklet focuses only on strategies for improving the composition area shown above as it relates to Writing Center tutors. Misconceptions/What LDs Are Not Misconceptions about LDs impede educators' abilities to provide high level instruction. Many people consider students with LDs less intelligent, mildly retarded, or even emotionally disturbed. Nothing could be further from the truth. These theories are antiquated, inappropriate, and wrong. Students with LDs have average or above average intelligence, "learning disabilities occur across the entire IQ spectrum, and the importance of perceptual problems in learning [cannot be overlooked]" (Wong 6). Wong states that "essentially, the child, adolescent, or adult with learning disabilities is a person whose academic or cognitive performance is out of line with his or her measured intelligence" (28). In other words, cognitive performance falls below measured intelligence. In fact, intelligence tests themselves can be flawed when used to measure the IQ of a person with LDs: "[individuals with LDs] showed a discrepancy between their measured intelligence and their achievement levels in standardized tests in reading, arithmetic, spelling and writing" (Wong 34). Students with LDs "were handicapped by their reading disabilities to perform well on intelligence tests that tap verbal knowledge and concepts. Because... [these] adolescents do not read, they lose out on learning much that is contained in intelligence test items" (Wong 34). Clearly, the misconception that people with LDs are less intelligent than are their peers stems from their limited output ability, not their intrinsic aptitude. Students with LDs are not mildly retarded, "children, adolescents, and adults with learning disabilities have adequate intelligence... someone with learning disabilities tends to show peaks and troughs in the performance profile" (Wong 44). Wong further states that "in contrast, mentally retarded individuals tend to show a very flat performance profile on a given test, with performance in the subtests consistently falling well below average" (Wong 44). People with LDs do not exhibit obvious sources for their learning difficulty, what researchers call "hard signs" (neurological evidence visible using x-rays or magnetic resonance imaging). Rather, people with LDs exhibit "soft signs." Soft signs are "soft neurological signs [that] involve an awkward gait, minimal tremors, and visuomotor coordination problems. Detection of these soft signs depends on the skills and subjectivity of the neurologist, because they are subtle abnormalities" (Wong 8). Another key difference between people with LDs and individuals who are mentally retarded is the ability to adapt. Mentally retarded individuals cannot adjust to changing environments as effectively as do people with LDs. Wong states that individuals with LDs overcome their learning problems: "the second and equally important criterion is adaptive skills, which refer to an individual's abilities to cope with his or her environmentt' (44). The mentally retarded are limited in their self-help skills, whereas students with LDs often rely upon their ability to work around their limitations to survive academically. The misconception that people with LDs are mildly retarded, again, stems from their inconsistent production, not from their inborn intelligence. Students with LDs are not emotionally disturbed, "individuals with learning disabilities have emotional problems that are associated with their histories of academic failure. But these emotional problems can be ameliorated and appear to subside as the learningdisabled person achieves academic success or improvement" (Wong 45). People with LDs deal with more problems than do individuals who learn traditionally. The frustrations of everyday life are compounded by the difficulty absorbing, processing, and producing information. The misconception that students with LDs have emotional problems probably stems from cases of hyper-activity and anger vented by people possessing average to above average IQs who perform poorly in school. It is our job as educators to erad'cate these misleading trends concerning LDs. Students with LDs are unique. They have adequate intelligence, yet score low on some tests. Students with LDs have difficulty learning, so at times do poorly in school. These shortcomings can lead to emotional stress. This stress can, in turn, isolate LD students from their peers. Yet the root of their difficulty is not ability, or a lack of adaptability; the root of the issue is their process of learning. Knowing this, we can develop multi-sensory approaches to assist LD students in the Writing Center. General Suggestions for Tutoring Students with Possible LDs Before outlining suggestions for specific writing problems, it is wise to underscore some overall strategies for tutoring students with LDs. First and foremost, tutors must remember that clients are probably very nervous. Even if students discuss an LD with their tutor and seem comfortable, they may still be anxious. If a client does not realize he/she has an LD, (or possibly knows he/she has one, and does not wish to disclose it), tutee anxiety will probably be even higher. So the first step is to "without being condescending, make [the student] feel comfortable about asking for and receiving help" (Ryan 45). Also, "if students tell you they have a learning disability but do not offer information about their coping strategies, ask" (Ryan 45). Be careful when asking clients whether or not they have an LD. Clients may not feel comfortable discussing these difficulties during the first tutoring session. If you suspect a student may have an LD, you should consider the following: Attitude: Be positive and friendly. Sessions always proceed smoother when apprehension, mistrust, and anxiety are abated. Accept the student as he/she is, do not be judgrnental. Let the student know that their anxiety is understandable, but that most writing problems can be overcome with practice and hard work. Try to relax; create an easy atmosphere for learning. Anxious clients will tune into a relaxed aura, and in turn calm down. Pay attention to all non-verbal communication. Pay attention to the signals you send, as well as the signals sent by the client. Be creative. Try to think of new ways to convey what you are expressing rather than repeating something over and over. Be aware that a student with LDs may make the same mistake again and again. Do not assume that the student is lazy or has not been paying attention. Be patient. Explain things clearly and repeat or rephrase if necessary. Techniques: Present information in as many ways as possible; say it and write it, draw it and discuss it. Use visual information as much as possible. Diagrams, charts, pictures, and colors tap into essential multi-sensory learning. Use auditory reinforcement of visually presented material. Have clients read notes and papers aloud; read corrections made to the paper aloud. Suggest the use of a tape recorder during the session, and also for proofreading alone. Using tape recorders reinforces auditory learnihg. Use gestures when explaining a point. Be animated-point, circle the information, draw a picture, act it out-involve yourself in the information. Make rearrangements of items a physical activity for the student. Instead of drawing arrows to indicate where a sentence or paragraph should be moved to, put information on separate pieces of paper the student can rearrange. Allow the student to do the writing, copying, underlining, highlighting, moving. When presenting new information, clarif' its relationship to the previously presented information. Encourage composition using word processing software. Editing text takes much less time, and assignments are more easily completed. Avoid using unnecessarily long sentences and esoteric words. Many LD students have difficulty understanding complex spoken language. Relate a writing subject to real lile experiences. Teach mnemonics (FANBOYS etc.) to help memorization. Format the same structure for tutoring sessions if the tutee is seen regularly. Provide specific feedback rather than general statements. Explain why something is unclear, or vague, or awkward. Suggest details; tutors cannot i;e general in their instruction. Tell students what you are going to teach them, teach it, tell them what you taught them; review what you've covered at the end of the session. (This list was compiled from The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors, The St. Martin's Sourcebook for Writing Tutors, Success for College Students with Learning Disabilities, and College and the Learning Disabled Student.) These techniques outline some important guidelines to which tutors should adhere. Detailed suggestions for specific areas of learning difficulty are covered in the following sections. They are broken down into the two following categories: how to recognize global writing problems, their short-term and long-term solutions, and how to recognize grammar problems, their short-term and long-term solutions. The following section outlines how to spot global errors endemic to compositions produced by LD students. "A Writing Center can be advantageous for the college student with LDs who seeks assistance with writing. Labs also offer less standardized and more personal approaches to writing. Overall, they provide obvious reinforcement of the writing courses and become an important factor in alleviating students' writing anriety" (Vogel/Adelman 219). II. How to Read the Signs: Recognizing Global Writing Problems Short and Long-Term Solutions to Global Writing Problems Tutors encounter many composition problems during a session. We are taught to focus first on global issues like clear theses, supporting ideas, smooth transitions, and concise conclusions. After reviewing the work with the student to evaluate these criterion, we can then focus on detailed grammatical issues like dangling modifiers, run-on sentences, and punctuation problems like comma splices and the correct use of semicolons. In most cases, however, tutors work on one area or the other because clients prefer to work on global problems or problems with grammar rather than both at the same time. Unfortunately, students with LDs might have difficulty even getting to grammar issues. For LD students, the entire writing process can be a problem: "specifically, they lack knowledge of the writing process... such as what writing is about, its purpose, and what constitutes a good writer" (Wong 195). Additionally, Charles Mangrum states in College and the Learnin~ Disabled Student that people with LDs "demonstrated a lack of understanding of the meaning of certain cohesive ties they used in their writing... [it appears that] the problem is one of understanding as well as production" (27). Therefore, compositions that lack structure and focus, wander from one abstract idea to another, and do not develop supporting ideas could be the work of a student with an LD. Keep in mind, however, that some of these symptoms are also signs of young, inexperienced writers. Do not assume that one or two of these signs means a client has an LD. Rather, look for papers that exhibit a number of, or combination of, these characteristics. Here are some quick global clues to look for when reviewing writing: Lack of clear, concise thesis or main idea for an essay or paper Unorganized paper format (paragraph organization) Lack of main ideas for paragraphs (topic sentences) Inconsistent sequencing of events and ideas Insufficient evidence supporting main idea or thesis Repetition of ideas stated in different ways to expand essay or paper Lack of cohesive ties from one idea to another (transitions) Inability to distinguish important from unimportant information Insufficient length of composition This is by no means a comprehensive or complete list of every global problem students with LDs can exhibit. Rather, this list outlines some severe weaknesses, that in combination with the grammar errors listed in the next section, can indicate LDs in clients using the Writing Center. Short-Term Solutions for Global Writing Problems Even though most Writing Center sessions last for only thirty to sixty minutes, tutors aware of short-term solutions to LD global writing problems can significantly improve their composition instruction. After recognizing the possibility of an LD, a subtle shift in approach can mean the difference between a successtul or unsuccessful session. The following information is intended to help tutors quickly adjust to a student that may have an LD. These short-term solutions can help students with LDs improve their writing. However, it is imperative to remember that Writing Center tutors are not LD instructors extensively trained in providing LD programs for composition. Please remember that learning to write well is a long-term process. For people without LDs, writing can be very difficult. For students with LDs, writing can be a formidable task, a task sometimes seeming impossible to achieve. There are no quick-fix solutions that will miraculously transform a student into William Faulkner in thirty minutes; however, the following ideas will allow tutors to approach a possible LD student differently. Tutors will be better equipped so that success may be achieved. Clearly Presenting and Supporting a Main Idea or Thesis Strategies for organizing papers and paragraphs, topic sentences, establishing proper sequence of ideas, providing supporting evidence, avoiding repetitive ideas, creating idea cohesion, discarding unimportant information, and avoiding insufficient length of papers. Probably the most important global issue facing students with LDs is the ability to tell the reader what a paper or essay is attempting to say, then following a logical, systematic process to provide evidence of the stated purpose. Whether the work is an argument composition, a compare/contrast paper, or a research study, providing concise justification in the opening section is imperative. This information, or direction, is provided by the thesis. Without clear direction, writers tend to wander. When writers stray, evidence justifying the thesis statement is unorganized and misplaced, conclusions are anemic and unconvincing. Most of the time, a good outline is the writer's best friend. Outlines ensure theses are supported by an organized array of facts pointing readers to the intended conclusion. Outlines are the best place to start for clients unable to organize. For many students with LDs, however, merely verbalizing suggestions about an outline is useless. These suggestions tend to drop dead in the tutoring cubicle. Tutors must use a multi-sensory approach with LD students to really drive home the point. The best method for constructing an outline during a tutoring session is moving information the student has already provided to a blank piece of paper. Moving the information to a separate piece of paper allows clients to concentrate on the basic facts they have already compiled. Even a small amount of information can be reorganized so ideas flow systematically. This method helps clients see graphically how the paper should flow. Unfortunately, many students with LDs do not always think in a systematic fashion; in other words, outlines just do not work for them because their brains do not process information in an outline manner. Vogel and Adelman state that sequential thinking and categorizing during the writing process can be a problem for LD students to begin with. Therefore, other graphical alternatives are preferable. The following diagram, modified from the original developed by Wong, can be used for the entire paper, or for individual paragraphs within the essay (163): Figure 2 Graphically organizing ideas to support thesis or topic sentence. It must be made very clear to clients with possible LDs that supporting the main idea will legitimize their composition effort. Lack of supporting detail is usually the cause of short papers. Clients need to realize that if they provide enough support for their thesis, length will usually be no problem at all. Avoid generalities; be specific! Another good diagram to use is an offshoot of the clustering or branching technique used to develop ideas for a composition. Originally, this technique was used to brainstorm; however, it has been modified here as a combination of brainstorming, pseudo-systematic organization, and the diagram in Figure 2. This diagram represents an informational paper on LDs: Figure 3 Clustered organization of a paper with a main idea supported by detailed, supporting information Other graphical layouts can be used to break down information into a compare/contrast format The diagram in Figure 4, developed by Wong, combines features from both an outline and a branch format. This example compares and contrasts features of Tom Stoppard's play Arcadia with T.S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land: Figure 4 Plan sheet for compare and contrast essay An excellent graphic reminder for constructing an opinion essay was also created by Wong. The diagram in Figure 5 highlights key words LD students can use at every juncture of their paper: Figure 5 Opinion essay writing prompt card Drawing an inverted pyramid showing the progression from general information to detailed information is also an excellent graphical demonstration: Figure 6 Organization of information progressing from general to detailed facts Tutors should integrate as many graphical aides as possible to demonstrate the organization of information in papers and paragraphs. Though global problems are the most serious issues tutors address, they can be the easily demonstrated using visual aids (grammatical problems are not as easily conveyed using graphics). As was previously stated, students with LDs are multi-sensory learners; the more color and visual assistance tutors use, the higher the chances are for teaching successfiii writing! Long-Term Solutions for Global Writing Problems Even though most tutoring sessions are short4erm, clients who experience success in the Writing Center often return on a regular basis. These return visits may augment clients' work in the Students with Disabilities Program, or the visits may be the sole source of continued composition instruction. With this in mind, the following techniques are designed to assist clients who return to the Writing Center on a somewhat regular basis, and who work with tutors over a longer period of time. People tend to avoid difficult tasks, or tasks that require an extensive amount of time to complete. Regardless of our work ethic, we tend to procrastinate unpleasant chores, especially if they posses negative emotional stigmas. Students with LDs are no different. Reading and writing are tasks that usually require large amounts of time and effort. Therefore, LD students usually do not read or write for pleasure; they do not practice these essential skills on a daily basis, and so when they are required to read or write, it is that much more difficult for them. Wong states that "these students have a production problem, i.e., they write [very] little in the face of the amount of time given in writing). Constrained by a poor vocabulary, they experience much difficulties in finding felicitous words to express their communative intents" (212). A good way to combat this lack of production is the daily journal. Journals positively impact two areas of clients' lives: journals provide an outlet for students with LDs to record or comment on life experiences (providing a healthy channel for stress and frustration that may occur during the college semester), and they give students a chance to practice essential writing and editing skills. Journals allow students an open forum in which to express views on events that impact them directly. Students can write about topics that interest them with no anxiety about composing for a grade. Journals are an open format in which different areas of composition can be explored. For example, entrees might be free-flowing brainstorms about everything and anything that comes to mind. During the tutoring session, ideas or topics can then be organized into possible theses for a short weekly essay (perhaps one page). Beginning with broad, main ideas, students can work on providing detail to the initial thoughts recorded in the journal. From there, students can work on organizational skills that can be applied to longer, assigned works. Grammar level instruction can occur after students grasp the basics of overall organization. Grammar skills should be practiced once students learn how to support a thesis. Another excellent method for teaching long-term global composition skills is the POWER plan. POWER is an acronym for Plan, Organize, Write, Edit, and Revise/rewrite. The POWER plan provides students with LDs specific steps that, when combined with techniques previously outlined, can guide them along the road of composition. The POWER plan allows students to "ascertain for themselves their purpose in writing, and to search their long-term memories for ideas or topics to write about" (Wong 202). The POWER plan breaks down as follows: Plan o o o Why am I writing this? Who am I writing for? What do I know? (brainstorm) Organize o How can I organize my ideas into categories? o How can I organize my categories? Write (rough draft) Edit o Reread and think o Which parts do I like best? o Which parts are not clear? o Did I do the following: Stick to the topic? Support the thesis? Talk about each category clearly? Give details in each category? Use active words? Make the paper interesting? Revise/rewrite o Use a ruler to isolate sentences o Read out loud o Use a dictionary and a thesaurus o Reread and revise as many times as needed The POWER plan is an excellent checklist for students with LDs to use to build self-help composition skills. Global issues are the most important obstacles students with LDs must hurdle. Unless students' compositions follow a logical process, and unless their work provides detail that supports the main idea, students will not be able to progress beyond the freshman, or entry-level college courses. Although grammar issues cannot be overlooked, the ability to lay out an organized argument is paramount to students' success in college. Keep in mind, however, that students with LDs may always struggle with organization. Once global issues are addressed and progress has been made, tutors can then outline some grammar issues that may appear in a client's compositions. How to Read the Signs: Recognizing Grammar Problems Short and Long-Term Solutions to Grammar Problems A Word on Style Beyond organization difficulty and logical idea structure, students with LDs usually encounter obstacles with grammar. Subtleties like dangling modifiers, run-on sentences, and punctuation problems like comma splices and the correct use of semicolons tend to elude students with LDs. Wong states that LD students "have difficulties in structuring sentences. - their written products are replete with errors in spelling, punctuation, and grammar (212). Further, Mangrum states when "overall, spelling and punctuation errors distinguished the LD writers from the non-LD writers... non-LD writers used more prepositional phrases, and a greater number of gerunds, participles, and absolutes... as well as greater main clause word length" (28-9). Clearly, in order to ensure college level writing among LD students, tutors must be aware of, and be able to correct, these grammatical shortcomings. However, finding grammar errors tends to be easier than correcting them. Grammar mistakes are not as easily corrected as global issues because grammar problems are not as easily represented in graphical formats. Also, grammar rules can be extensive and confusing. Subsequently, tutors may be tempted to merely insert a comma or a semicolon without explaining all the rules. Tutors must resist this temptation. Tutors must discuss every step of the writing process with LD clients in order to teach effective strategies for overcoming their difficulties. It may be intimidating for clients to incorporate both global and grammar strategies, but only a happy marriage of these two areas will improve their writing, and ensure success. Remember to stay positive! Good attitude translates into a successflil session. Try to recall an area in which you have difficulty. This will allow you to relate to the frustration students with LDs may be experiencing. The techniques included in this handbook can help tutors help students with LDs catch and correct some of the more serious grammar mistakes. The following list is a touchstone for tutors to use to examine possible combinations of weaknesses. Again, keep in mind that some of these symptoms are also signs of young, inexperienced writers. Do not assume that one or two of these signs means a client has an LD. Rather, look for papers that exhibit a number of, or combination, of these characteristics. Here are some quick grammar clues to look for when reviewing writing: Lack of capitalization Spelling difficulty o correct order of letters in words (confusing b's, h's, d's, e's, a's, etc.) o discriminating homonyms (their-there, its-it's) Comma omissions and incorrect insertions Omissions of articles, demonstratives, and prepositions Dropped endings Sentence structure o writing incomplete sentences o inability to express ideas precisely and clearly within a sentence, vagueness (indefinite words, or phrases like "This thing that" or "It's something like.") o difficulty varying sentence style (subject-predicate I short, compound sentences vs. longer, complex work that incorporates prepositional phrases, and absolutes, as well as greater main clause word length) o a number of run-on sentences and dangling modifiers Difficulty using mature syntactical patterns Lack of sufficient number of verbs, adverbs, and adjectives (flat writing) Difficulty using an appropriate range of vocabulary (paucity of vocabulary) Difficulty using words in appropriate context (semantic problems like discerning the difference between words that have multiple meanings: glasses, running, short, loudly, at, etc.) Difficulty pronouncing longer words Inability to record grammatical errors (proofreading) Inability to vary style to match purpose and requirements This is by no means a comprehensive or complete list of every grammar problem students with LDs can exhibit. Rather, this list outlines some severe weaknesses that in combination with the global errors listed in the previous sections, can indicate LDs in clients using the Writing Center. Short-Term Solutions to Grammar Problems Even though most Writing Center sessions last for only thirty to sixty minutes, tutors aware of short-term solutions to LD grammar problems can significantly improve their composition instruction. After recognizing the possibility of an LD, a subtle shift in approach can mean the difference between a successfiil or unsuccessful session. The following information is intended to help tutors quickly adjust to a student that may have an LD. These short4erm solutions can help students with LDs improve their writing. However, it is imperative to remember that Writing Center tutors are not LD instructors extensively trained in providing LD programs for composition. Please remember that learning to write well is a long-term process. For people without LDs, writing can be very difficult. For students with LDs, writing can be a formidable task, a task sometimes seeming impossible to achieve. There are no quick-fix solutions that will miraculously transform a student into Jane Austen in thirty minutes; however, the following ideas will allow tutors to approach a possible LD student differently. Tutors will be better equipped so that some semblance of success may be achieved. Recognizing and Correcting Grammar Errors: Strategies for improving spelling, capitalization, punctuation, proofreading. Today, many grammatical errors are caught and corrected by sophisticated spell-check and grammar-check programs. These software applications help students with LDs substantially when writing. In fact, many sources on LD education recommend using these programs to assist students who have problems with grammar. However, these applications have their limitations: "[word processing programs] pick up (only] 25% of the grammatical errors and [only] 80% of the objectionable phrases in a document. These programs may also make incorrect suggestions" (Vogel/Adelman 246). Students with LDs must be able to correct grammar mistakes themselves in order to succeed in college. The following four tools are essential to ensure successful grammatical instruction: A dictionary A thesaurus A grammar handbook (A Writer's Reference, Diana Hacker, Bedford/St. Martin's, is a good start; The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, The Modern Language Association, is another excellent source for checking proper citation.) Plenty of time. These references form the spine of the grammatical tutoring sessions. Armed with these tools, tutor and client are prepared to tackle every kind of grammar problem. A good short-term strategy for helping students with LDs overcome spelling problems is the DISSECT method. DISSECT is an acronym for Discover the context, Isolate the prefix, Separate the suffix, Say the stem, Examine the stem, Check with someone, Try the dictionary. Breaking down a word using this method cuts away the intimidating extras attached to the beginning and ending of many roots. However, some students with LDs have basic phonic problems; the DISSECT method will not be as usetul to someone whose phonological processing skills cannot discern "information about the sound structure of our language in processing written and oral language" (Wong 15). Another good technique for improving spelling is maintaining individual spelling journals. Personal spelling books record words that are difficult for the client to spell. These records (with their corrections) can then be accessed during composition in order to avoid future mistakes. Also, these spelling journals can be used during editing so that clients can correct their own work (an important step in the learning process). Tutors should have the client write the misspelled word on a separate piece of paper, then allow the student correct the misspelled word on the other side, spelling it out loud. In Teaching One-to-One: The Writing Conference, Muriel Harris suggests using visualization to improve spelling: "visualization is very important in spelling competence, it is helpful to offer students strategies designed to improve their ability to focus attention on those letters in words which they have not noticed and therefore have not stored correctly in memory" (131). This technique allows for focused visualization recall of the word, spelled correctly, alone, on a blank sheet of paper. The more visual and auditory cues students with LDs utilize, the better their chances for success. Reference and memory techniques can be developed to associate commonly misspelled words with objects that trigger correct spelling. Again, try incorporating visual aides with these memory and association strategies. Approach a word from different angles, just like one would approach an idea from different angles for a paper. Assign certain aspects to words that will differentiate them from words the clients use incorrectly. For example, clari~ing the difference between plane and plain can be done using the following strategy. A synonym for plain is the word simple. Both the word plain and the word simple contain the letter i, a good connection. Plain, defined as simple, or easy, is no longer conflised with plane, defined as flat, because both plain and simple contain the letter i: see... it's simple! Another excellent strategy for improving spelling is simply using a dictionary whenever possible. See if teachers will allow the use of dictionaries for in-class writing for students with LDs. Clients may not want to divulge their LDs, however, so this process should be strictly left to the student. Finally, extensive proofreading is probably the best strategy for alleviating spelling problems. As tedious as it sounds, using a ruler to isolate sentences and words while editing is an effective technique, as is rewriting the problem word on another sheet of paper. This isolation separates the misspelled or misplaced word from the "noise" surrounding it in the composition. Often, when focused on one word, the client will easily detect and correct the word him/herself. Punctuation is a weak area for students with LDs as well. The following strategies address this difficult area and provide some stimulating techniques to overcome punctuation's intimidating challenge. Punctuation rules can be very difficult to remember. Often, when they are explained in grammar handbooks, the rules are imbedded in mounds of confusing text. The rules themselves are difficult enough to remember, so their presentation should not be as hard. Therefore, this diagram, borrowed from Teaching One-to-One: The Writing Conference, by Harris is used to clearly show the breakdown of punctuation: Figure 7 Punctuation pattern sheet To ensure proper sentence structure, whether it be eliminating dangling modifiers or run-on sentences, one of the best techniques to use is rewriting the questionable sentence on another sheet of paper. Isolating problems removes sentences from the "noisy" and distracting composition; isolation allows clients to focus on specific issues. Isolation allows concentration. One of the best techniques for remembering grammar terms is mnemonics. Here are some examples of mnemonics used to memorize some terms used in Figure 7: Coordinating Conjunctions, Correlative Conjunctions, Coordinating Adverbs, Subjunctive Conjunctions: CCCS Coordinating Conjunctions: FANBOYS - For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So. Correlative Conjunctions: NEBNN - Neither-nor, Either-or, But-and, Not onlybut also, Not only-but as well as Coordinating Adverbs: SHINTAF - So, However, k conclusion, Nevertheless, Therefore, Afterward, For example Subjunctive Conjunctions: PAWBAT - Provided that, As long as, When, Because, Although, Though Mnemonics help clients memorize large quantities of information, like the rules governing grammar. Long-Term Solutions for Grammar Problems Even though most tutoring sessions are short-term, clients who experience success in the Writing Center often return on a regular basis. These return visits may augment clients' work in the Students with Disabilities Program, or the visits may be the sole source of continued composition instruction. With this in mind, the following techniques are designed to assist clients who return to the Writing Center on a somewhat regular basis, and who work with tutors over a longer period of time. Using the daily journal can improve grammar as well as global issues. This process begins with practicing global areas of instruction, then carries over into the grammar areas. These daily journals can be used for long-term programs of composition study. However, tutors should concentrate on grammatical errors only when global errors decrease so as not to overwhelm clients with rules and strategies. Another excellent, multi-sensory method is color coordinating certain sentence structures. Students with LDs tend to create simple subject-predicate sentences without variation. These simple sentences lead to monotony in their writing. Using highlighters, tutors can color simple sentences green, color compound sentences yellow, and color complex sentences blue. Tutors can even break down parts of sentences like main clauses, dependent clauses, dangling modifiers, prepositional phrases and preposition strings, as well as predicates, nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, and, adjectives. One lesson can focus on sentence patterns, another lesson can focus on parts of speech. Try not to do too many color combinations at once, however. An entire rainbow of colors and rules might be overwhelming to students. Try to focus on three or four colors (items) per lessons. This technique allows students to visualize how their language patterns appear when highlighted in separate colors. By seeing a paper dominated by simple sentences (green), a client might finally discern the cause of the monotonous tone in his writing. Another excellent method for improving grammar over a long period of time is the COPS technique. COPS is an acronym for Capitalization, Overall appearance (of the paper), Punctuation, Spelling. Using COPS, students with LDs have a list of I reminders they can use to search for specific errors within their work. Sometimes proofreading may seem daunting. Students with disabilities might be hesitant to review their compositions because they need to look for so many areas of writing: global issues, grammar issues, etc. By giving students checklists they can use at difference levels of correction, tutors provide building blocks for clients to use on their own to tackle these complex composition corrections. By using these checklists, students with LDs can develop healthy writing habits on their own. A Word on Style One of the best ways to improve writing style is to read. Reading and then writing about what you read is essential practice for developing good sentence structure. Unfortunately, students with LDs do not tend to read for pleasure, and they write even less. Because of this lack of exposure to good writing, long-term programs like the ones mentioned in this booklet are excellent methods of cultivating constructive composition. Specific tasks assigned every week, along with joL[rnal entries, allow LD students to read and write. Journal entries allow students to develop skills that are sometimes incredibly difficult for them to grasp. Students with LDs need personal attention to improve their writing; they require someone reading what they write to show them mistakes they cannot see for themselves. Style is one of the main differences between LD and non-LD writing: "style, which included varied sentence structure and word selection, was the greatest overall discriminator between the writing of LD students and that of the non-LD students" (Mangrum 28). However, style tends to be the most complex aspect of writing to teach. Varying sentence pattern is probably the best place to begin improving writing style. Breaking up multiple ideas, isolating main thoughts in shorter sentences, eliminating incomplete sentences and dangling modifiers will help students acquire the ability to write clearly. As Mangrum stated, word selection is another area in which students with LDs need work. As difficult as it may seem for the client, having LD students read is probably the best way to expand their vocabulary. Tutors should use shorter magazine articles and compositions from Freshman English readers for long-term assignments. Regardless of which technique tutors use, the best way for clients to improve their style is to practice as much as possible. Vocabulary building games will also improve a student's style. IV. Conclusion The key to writing success for LD students is creating effective processes they can use to develop organized essays, or trigger grammar rules to construct good sentences. Therefore, many of the strategies in this booklet involve mnemonics, checklists, and visual diagrams LD students can use every time they write. The items, and the steps included in the strategies, may seem obvious and redundant to experienced writers who do not have LDs, but to students with disabilities, these strategies are the ladders to writing success. Each step is a rung in the writing ladder allowing LD students to climb to new heights of success in composition, and new heights of success in their college career. By visiting the Writing Center, clients express a desire to develop their composition skills. It is our job to provide superior writing instruction, and to provide stimulating methods of improving their technique. Hopetully, this booklet will assist tutors in their composition instruction for students with LDs, as well as improve instruction for students who are non-LD. Possessing a large vocabulary of teaching strategies is like possessing a large vocabulary of words, the wider the variety, the richer the writing! V. Works Cited Harris, Muriel. Teaching One-to-One: The Writing Conference. Urbana: NCT, 1986. Mangrum, Charles and Stephen Strichart. College and the Learning Disabled Student. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: HBJ, 1988. Murphy, Christina and Steve Sherwood. The St. Martin's Sourcebook for Writing Tutors. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995. Ryan, Leigh. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. Boston: Bedford Books, 1998. Vogel, Susan and Pamela Adelman. Success for College Students with Learning Disabilities. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1993. Wong, Bernice. The ABCs of Learning Disabilities. San Diego: Academic Press, 1996. VI. Works Consulted Kolin, Martha. Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices Rhetorical Effects. 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1998. Wug, Elisabeth and Eleanor Semel. Language Assessment and Intervention for the Learning Disabled. 2nd ed. Columbus: Merrill, 1984. Wug, Elisabeth and Eleanor Semel. Language Disabilities in Children and Adolescents. Columbus: Merrill, 1976. VII. Appendix Organizations Established to Assist the Learning Disabled. International Center for the Disabled 340 East 24th Street New York, NY 10010 (212) 679-0100 (212) 889-0372 (TDD) Association for Children and Adults with Learning Disabilities (ACLD) 4156 Library Road Pittsburgh, PA 15234 (412) 341-1515 Association of Learning Disabled Adults (ALDA) PO Box 9722, Friendship Station Washington, DC 20016 National Network for Learning Disabled Adults (NNLDA) 800 N 82 Street, Suite F2 Scottsdale, AZ 85257 (602)941-5112 Orton Dyslexia Society 724 York Road Towson, MD 21204 (301) 296-0232 (800)222-3123