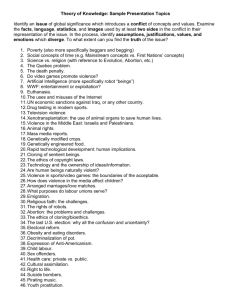

naval - Animal Liberation Front

advertisement