Michigan Public Officials - Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

advertisement

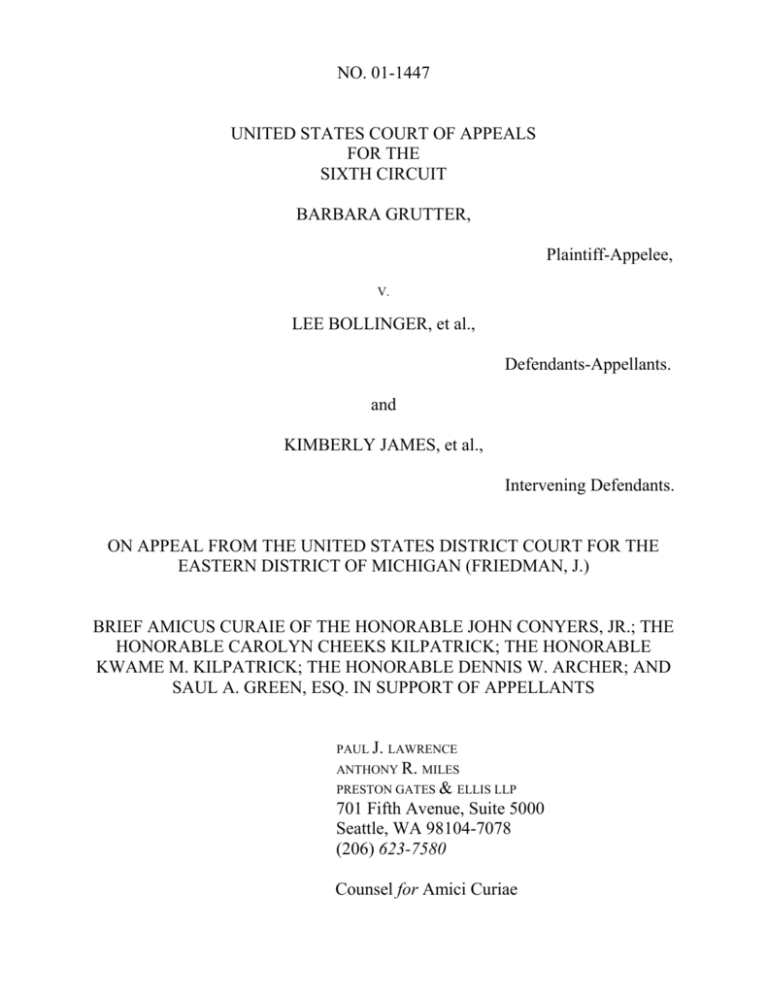

NO. 01-1447 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT BARBARA GRUTTER, Plaintiff-Appelee, V. LEE BOLLINGER, et al., Defendants-Appellants. and KIMBERLY JAMES, et al., Intervening Defendants. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN (FRIEDMAN, J.) BRIEF AMICUS CURAIE OF THE HONORABLE JOHN CONYERS, JR.; THE HONORABLE CAROLYN CHEEKS KILPATRICK; THE HONORABLE KWAME M. KILPATRICK; THE HONORABLE DENNIS W. ARCHER; AND SAUL A. GREEN, ESQ. IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS PAUL J. LAWRENCE ANTHONY R. MILES PRESTON GATES & ELLIS LLP 701 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5000 Seattle, WA 98104-7078 (206) 623-7580 Counsel for Amici Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE 1 ARGUMENT 4 TIlE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN'S UNDERGRADUATE AND LAW SCHOOL ADMISSIONS PLANS ARE CONSTITUTIONAL 4 A. State Institutions May Consider Race for Purposes Other Than Remedying Past Discrimination 5 II. DIVERSITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION IS ESSENTIAL TO AMERIC ~N DEMOCRACY AND IS A COMPELLING STATE INTEREST.... 11 A. The Law School's Desire to Admit an Integrated Class of Students is a Constitutionally Permissible Educational Purpose 11 B. The Law School's Desire to Admit an Integrated Class of Students is Also Constitutionally Permissible to Ensure Full Participation in the Political Process 13 1. An admissions process that virtually excludes certain communities of citizens from participation undermines the political legitimacy of state institutions 14 2. Reducing the diversity of students at elite state educational institutions will harm African Americans economically, educationally, and politically 18 CONCLUSION 23 —1— TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 US. 200, 115 5. Ct. 2097, 132 L. Ed.2d 158 (1995) 7 Agostiniv.Felton 521 U.S. 203, 117 5. Ct. 1997, 138L. Ed.2d 391 (1997) Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68, 99 5. Ct. 1589, 60 L. Ed.2d 49(1979) 14, 18 Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. ~upp. 582 (E.D. Mich. 1971) aff'd484F.2d215(6 C ir. 1973) 16 Brewer v. West Irondequoit Cent. Sch Dist., 212 F.3d 738, 144 Ed. Law Rep. 845 (2nd Cir. 2000) 12 Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 18 Buchwald v. University of New Mexico Sch. Of Med., 159 F.3d 487 (10th Cir. 1998) 6 Bushy. Vera,517U.S.952, 1165.Ct. 1941, 135L. Ed.2d248(1996) 9 City of Richmond v. Croson, 488 U.S. 469, 109 5. Ct. 706, 102 L. Ed.2d 854 (1989) 7, 8 Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S. 291 (1978) 14 Gratz v. Bollinger, Grutter v. Bollinger, 5 Mich. I Race & L.363 3,8,20,22 Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir. 1995) 7, 10 Huntv. Cromartie, 532 U.S. 121 5. Ct. 1452 (2001) 10,12 In re Grffiths, 413 U.S. 717,93 5. Ct. 2851,37 L. Ed.2d 910(1973) 23 Kramer v. Union Free Sch. Dist., 395 U.S. 621, 89 5. Ct. 1886,23L.Ed.2d583 (1969) 14 Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 91 5. Ct. 2125, 29 L. Ed.2d 745 (1971) 15 Millerv. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 115 S. Ct. 2475, 132 L. Ed.2d 762 (1995) 9,11 Millikenv.Bradley 418U.S. 717,94 5. Ct.3112,41 L. Ed.2d 1069 (1974) 16 Parents Involved in Community Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, CA COO-1205R, F. Supp .2d 2001 WL360610(W.D.Wasli7Apr. 6,20017 12 __, , —1— Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 102 5. Ct. 2382, 72 L. Ed.2d 786(1982) 15 UL26S,C~ v. Bakke, 438 Regents 98 5. 2733; 57 L. Ed.2d 750 (1978) passim Rios v. Regents ~f the Univ. of Cal., No. C99-0525 (N.D. Cal., filed Feb. 2,1999) Romerv. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 116 S. Ct. 1620, 134L. Ed.2d 855 (1996) 17 Shawv. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 113 S. Ct. 2816, 125 L. Ed.2d511(1993) 5 Smith v. Regents of the Univ. of Washington, 233 F.3d 1188 (9th Cir. 2000), cert. denied~, 69 U.S.L.W. 3593 (U.S. May 29, 2001) (No. 00-1341) 6 Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 70 5. Ct. 848, 94 L. Ed. 1114(1950) 3,11,23 United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S. 717, 112 5. Ct. 2727, 120L.Ed.2d575(1992) 17 Washing ton v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1,458 U.S. 457, 102 SCt. 3187, 73 L. Ed.2d 896 (1982), accord, North Carolina Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 91 5. Ct. 1284, 28 L. Ed.2d 586 (1971) 12 Wessman v. Gittens, 160 F.3d 790 (1st Cir. 1998) 6 Other Authorities William G. Bowen and Derek Bok, The Shape of the River: The Long-term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions, 119-62 (1998) 3, 19 —11— INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE This appeal presents the question: "for which purposes may a state university constitutionally consider race as one component of its admissions process?" Resolution of the question involves consideration of the role that accessibility and responsive of state institutions plays in enhancing the legitimacy of state government, and the role state educational institutions play in the political and economic well-being of a state's citizens. Amici, the Honorable John Conyers, Jr., Honorable Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick, Honorable Kwame M. Kilpatrick, Honorable Dennis W. Archer, and Saul A. Green, Esq., are present and former public officials who have devoted their lives to serving the people of the State of Michigan, with special emphasis on the Detroit metropolitan area. See Appendix (describing more fully the service of each of the Amici). Amici are deeply concerned about the viability of the political process in the State of Michigan and about the accessibility and responsiveness of governmental institutions to those whom Amici have served. Amici likewise take considerable interest in the enterprise of public education and the relationship between available education and the economic and political well-being of Michigan's citizens. Consequently, Amici have a significant interest in the accessibility of the University of Michigan to all of the state's citizens, including those in the metropolitan Detroit area, and believe —1— that considering race as one factor in the admissions process is an essential element of maintaining this access. Amici submit this brief in their individual and private capacities and not on the behalf of any legislative or executive agency of a local, state, or federal government. As present and former public officials at the local, state, and federal level, Amici have an abiding interest in the purposes for which state actors may take race into account in their decision making. Amici are concerned that, in adjudicating the challenges to the undergraduate and law school admissions programs at the University of Michigan, the district court overlooked significant recent Supreme Court decisions in the arena of redistricting, which provide a much broader range of permissible purposes for multiple-criteria, race-conscious governmental decision making. Amici fear that if replicated by this Court, the district court's oversight might result in a decision that unduly restricts the range of circumstances in which state institutions can consider race as one factor in decision making. Thus, Amici seek to draw this Court's attention to these precedents in the hope of assisting the Court in reaching a decision that appropriately accounts for the contextual differences between public education and other enterprises. Amici are further concerned that reducing or eliminating the level of diversity among University of Michigan students will have damaging effects on the -2- enterprise of public education, the political process, and the educational, material and political circumstances of Amici ~ constituents. Research has demonstrated that attendance at highly selective colleges and universities enhances educational and material success, as well as political and civic participation. See, e.g., William G. Bowen and Derek Bok, The Shape of the River: The Long-term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions, 119-62 (1998). Likewise, research has confirmed the Supreme Court's conclusion in cases such as Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 70 5. Ct. 848, 94 L. Ed. 1114 (1950), that having a student body that reflects the full spectrum of societal diversity improves the quality of higher education. Expert Report of Patricia Gurin, Gratz v. Bollinger, Grutter v. Bollinger, 5 Mich. .1 Race & L. 363, 399-40 1. Amici believe that the University of Michigan must continue to support the advancement of members of all of Michigan's communities and to maintain the quality of the educational environment made possible by the diversity of its current enrollment. To fail to do so will undermine the political legitimacy of public education as a state enterprise, and Amici's constituents' ability to obtain effective representation through the political process. If the University of Michigan is not able to consider all aspects of each applicant's background, including race, as factors in its admissions process, Amici -3- fear that all future graduates of the University of Michigan will lack the skills and experiences available to those who attend racially-diverse educational environments. Such individuals will be less likely to participate in the political process and may be less effective as political leaders. More importantly, reducing the diversity among the University of Michigan student body likely will deny significant communities within Michigan the ability to fully participate in the political and economic benefits of society. For these reasons, Amici add their voices in support of the University of Michigan Law School's admissions policy and ask this Court to uphold the use of race as one factor in the admissions process to institutions of higher education. ARGUMENT 1. THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN'S UNDERGRADUATE AND LAW SCHOOL ADMISSIONS PLANS ARE CONSTITUTIONAL This court is asked to decide whether the U.S. Constitution permits a state to provide access to its public institutions to members of each of its communities of citizens by using race as one of several factors in decision making. Amici believe that it does. Applicable Supreme Court doctrine attests to a state's ability to consider race as one among many factors for a variety of purposes, depending upon the context of the decision making. Likewise, federal court decisions support the determination that a state has a compelling interest in (1) obtaining the -4- educational and political benefits that flow from diversity; and (2) preserving access for its minority citizens to the opportunities for full political, economic and educational participation. Amici therefore urge this Court to hold that the University of Michigan's policy of considering race among other factors in admissions is within the ambit of state action authorized by the Fourteenth Amendment. A. State Institutions May Consider Race for Purposes Other Than Remedying Past Discrimination. Recent voting rights decisions confirm that the Equal Protection Clause does not limit state consideration of race only to remedies for specific instances of identified discrimination. The Supreme Court "never has held that race-conscious state decision making is impermissible in all circumstances." Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 642, 113 5. Ct. 2816, 125 L. Ed.2d 511 (1993). A review of the Supreme Court's Equal Protection jurisprudence demonstrates that the Equal Protection Clause may accommodate the use of race for different purposes, depending on the context in which the state decision making occurs. The Supreme Court's voting rights decisions and federal court decisions in the arena of education demonstrate that race may be considered in admissions criteria to achieve otherwise legitimate public goals as long as race or achievement of quotas is not the predominant criterion or goal. -5- In Regents of the University of Cal~fornia v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 98 5. Ct. 2733; 57 L. Ed.2d 750 (1978), Justice Powell and four other Justices held that, in the context of higher education, a state institution seeking to create a diverse class could consider race as "one element . . . in the selection process," so long as that process was not shown to be the functional equivalent of a quota system. 438 U.S. at 318-20. The Supreme Court has never overruled Bakke. See Smith v. Regents of the Univ. of Washington, 233 F.3d 1188, 1200 (9th Cir. 2000), cert. denied, 69 U.S.L.W. 3593 (U.S. May 29, 2001) (No. 00-1341) (applying Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke, and stating that the Supreme Court has not indicated that the analysis applied to consideration of race in higher education as outlined in Bakke has lost its vitality). As the last statement to command a majority of the Supreme Court on the use of race in higher education admissions, Justice Powell's opinion an Bakke controls the adjudication of challenges to a public university's admissions program. Smith, 233 F.3d at 1200; Buchwald v. University of New Mexico Sch. Of Med., 159 F.3d 487, 499 (10th Cir. 1998) ("Bakke remains the leading jurisprudential authority" in challenge to medical school admissions policy); see also Wessman v. Gittens, 160 F.3d 790, 795 (1st Cir. 1998) (stating that "Bakke remains good law"); cf, Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203, 237, 117 5. Ct. 1997, 138 L. Ed.2d 391 (1997) (only the Supreme Court has the prerogative of overruling -6- own decisions). But see Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932, (5th Cir. 1995) (ruling that Bakke framework was repudiated by later Supreme Court decisions and did not govern challenge to state law school admissions plan). Under Bakke, a state university that utilizes race as one of many elements in an admissions program is entitled to a presumption of good-faith, in the absence of evidence that its plan is the equivalent of a quota system. 438 U.S. at 318. The deference mandated by Bakke establishes that, in the context of higher education, state institutions' consideration of race in admissions is permissible for reasons other than remedying past racial discrimination. Subsequently, the Supreme Court's decisions in City of Richmond v. Cros on, 488 U.S. 469, 109 5. Ct. 706, 102 L. Ed.2d 854 (1989) and Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 US. 200, 115 S. Ct. 2097, 132 L. Ed.2d 158 (1995) suggested that consideration of race in the awarding of government contracts may be limited to situations designed to remedy identified instances of discrimination. Neither Croson nor Adarand, however, addressed the arena of education and neither decision purported to overrule Bakke. Amici believe that Croson is inapposite to the present case for three reasons: 1) the facts in Croson do not present the unique considerations that apply to consideration of diversity in higher education; 2) Croson addresses government -7- decision making in a purely local context, rather than the national admissions pool that selective institutions of higher education have to draw from; and 3) Croson does not address situations in which race is only one of many factors that contribute to a determination of how to allocate government resources for which all applicants are eligible for consideration. Nonetheless, should this Court determine that Croson is applicable to the issues raised by this appeal, Amici note that Croson suggests that a state institution has a compelling state interest in using a racial classification to ensure evenhanded access to tax-funded programs among all groups represented in the appropriate population. Croson, 488 U.S. at 503, 109 S. Ct. 706, 102 L. Ed.2d 854. On this basis, the University of Michigan's admissions policy would be constitutional. The University of Michigan has introduced evidence demonstrating the segregative impact of removing race as a factor in admissions. See Expert Report of William G. Bowen in Gratz v. Bollinger, 5 Mich. J. Race & L. 427, 435 (1999) ("Bowen Report"). Likewise, the University has introduced evidence demonstrating the high degree of geographic racial isolation in Michigan and the close relationship between such isolation and access to educational resources. See Expert Report of Thomas J. Sugrue in Gratz v. Bollinger, and Grutter v. Bollinger, 5 Mich. J. Race & L. 261, 276-80, 289, 292 (1999) ("Sugrue Report"). Croson -8- indicates that this evidence would support the constitutionality of an admissions plan that placed considerably greater emphasis on race, and that in crafting its plan, the University of Michigan Law School appropriately exercised its discretion by limiting race to one of a number of criteria considered in admissions decisions. Recent cases in the redistricting arena demonstrate the continued vitality of Bakke's deference to state multiple-criteria decision making. Acknowledging race as one of the numerous considerations taken into account in legislative redistricting, the Supreme Court held that governmental actors are entitled to a presumption of good faith in Equal Protection challenges to such plans, unless the claimant establishes that race is the predominant factor motivating the decisions. See, e.g., Millerv. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 915, 115 5. Ct. 2475, 132 L. Ed.2d 762 (1995) (challenge to Georgia legislature's congressional redistricting plan); Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 958-59, 116 5. Ct. 1941, 135 L. Ed.2d 248 (1996) (requiring preliminary inquiry to determine applicability of strict scrutiny in racial gerrymandering challenge to redistricting plan). Most recently, the Supreme Court held that a three-judge panel of the federal district court for the Eastern District of North Carolina committed clear error where the panel concluded that the North Carolina legislature's use of racial data as part of its redistricting process was constitutionally impermissible. Hunt v. -9- Cromartie, 532 U.S. 121 5. Ct. 1452, 1459 (2001) ("Cromartie IT'). In Cromartie __, II, the state considered incumbency protection, political voting behavior, and geographic commonality of interest among communities included in the districts, in addition to race. 532 U.S. at 121 5. Ct. at 1464. ___, These recent precedents belie the notion, expressed by the Fifth Circuit in Hopwood, that Bakke's more flexible approach to evaluating constitutional challenges to race-conscious governmental decision-making in education has been eliminated by the restrictions the Supreme Court has imposed on the use of race in the context of government contracting. Rather, these decisions demonstrate that a state institution may constitutionally consider race as one part of a decision making process for reasons other than remedying past discrimination. The Supreme Court's application of the Equal Protection Clause in the arenas of redistricting and higher education establishes that state institutions may consider race as part of multiple-criteria decision making. Depending upon the context of the program under evaluation, a state actor may consider race for purposes other than remedying specifically-identified discrimination. In light of these decisions, the University of Michigan's admissions plans cannot be invalidated simply because they were not adopted to remedy historical discrimination. Rather, the University of Michigan's policy of considering race as -10- one among several factors in admissions, is constitutional so long as it promotes a legitimate state interest and race is not the determining factor in the University's policies and programs. See Miller, 515 U.S. at 915, 115 5. Ct. 2475, 132 L. Ed.2d 762. II. DIVERSITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION IS ESSENTIAL TO AMERICAN DEMOCRACY AND IS A COMPELLING STATE INTEREST A. The Law School's Desire to Admit an Integrated Class of Students is a Constitutionally Permissible Educational Purpose As Justice Powell recognized in Bakke, the attainment of a student body "as diverse as this nation of many peoples" constitutes a compelling state interest under the Equal Protection Clause because a diverse student body assists state colleges and universities in fulfilling their educational missions. 438 U.S. at 311- 12. As controlling precedent, Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke governs whether diversity provides adequate justification for the University of Michigan's consideration of race to create an integrated class of students. However, Bakke is far from the only source of authority in this area. The federal courts' recognition of diversity as a constitutionally-permissible justification for the actions of state legislatures and school boards is both older and broader than Bakke. In Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 70 5. Ct. 848, 94 L. Ed. 1114 (1950), the Court noted that among the deficiencies of the black law school —11— established by the University of Texas was the exclusion of all non-black students. 339, U.S. at 634, 70 5. Ct. 848, 94 L. Ed. 1114. When reviewing challenges to legislative or school board actions that sought to combat geographic racial isolation with racial assignment policies, decisions by the federal courts generally support state efforts to provide integrated educational experiences to local primary and secondary school children. For example, the Supreme Court held that the decision to implement a mandatory racial busing plan to address de facto segregation resulting from racial isolation in housing patterns was an appropriate exercise of the school board's discretionary authority. See Washington v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 458 U.S. 457, 460, 102 5. Ct. 3187, 73 L. Ed.2d 896 (1982), accord, North Carolina Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 45, 91 5. Ct. 1284, 28 L. Ed.2d 586 (1971) ("as a matter of educational policy, school officials may well consider that some kind of racial balance in the schools is desirable, quite apart from any constitutional requirements"), Brewer v. West Irondequolt Cent. Sch. Dist., 212 F.3d 738, 752, 144 Ed. Law Rep. 845 (2nd Cir. 2000); Parents Involved in Community Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, CA COO1205R, ___ F. Supp.2d , 2001 WL 360610 (W.D. Wash., Apr. 6, 2001). Similarly, Cromartie II permits a state legislature to consider "racial balance" as one factor in crafting a redistricting plan. See 532 U.S. at ____, 126 5. Ct. at 1464. -12- This historical judicial recognition of the value of racial balance as a constitutionally-valid state objective in areas outside government contracting demonstrates that, in pursuing a racially-integrated student body through its admissions program, the University of Michigan Law School acted inside the bounds of constitutional limits. To the extent that the Law School's admissions plan seeks to provide educational benefits associated with racial diversity in the classroom, and to counter the forces leading to or effects resulting from racial isolation, its use of race as one of several admissions criteria falls well within the scope of objectives that courts traditionally have thought compelling and permissible under the Equal Protection Clause. B. The Law School's Desire to Admit an Integrated Class of Students is Also Constitutionally Permissible to Ensure Full Participation in the Political Process Maintaining a diverse student body at flagship state universities everywhere is also critical to maintaining the efficacy of a pluralistic, democratic society. The inclusion of members of each of the state's communities is critical to obtaining full participation by all members of society in the political process, and to addressing the political effects of racial isolation via state-sponsored opportunities in higher education. Amici believe that averting the inevitable reduction of the state's ability to draw upon enhanced political participation and representation, as discussed in -13- more detail below, also supports judicial recognition of diversity as a compelling state interest. 1. An admissions process that virtually excludes certain communities of citizens from participation undermines the political legitimacy of state institutions Born from the idea that a government that fails to provide for representation of the people it seeks to govern is illegitimate, our constitutional system provides that governmental institutions ultimately derive their authority and powers from their constituents. As current and former public officials, Amici are acutely aware of their function as representatives and their obligation to serve their constituents' needs. Individually and institutionally, elected officials are accountable to the people through the electoral process. Our system presumes that, by this process, a legislature will fairly reflect the interests of its constituency. See Kramer v. Union Free Sch. Dist., 395 U.S. 621, 627-28, 89S. Ct. 1886, 23 L. Ed.2d 583 (1969). Like state legislatures, flagship state universities are public institutions that must be accessible to all people. As the Supreme Court noted, "Public education, like the police function, 'fulfills a most fundamental obligation of government to its constituency.' Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68, 76, 99 5. Ct. 1589, 60 L. " Ed.2d 49 (1979) (quoting Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S. 291, 297 (1978)). Systems of public education were established in part to support the expansion of democratic rights and economic mobility associated with the advent of Jacksonian democracy -14- and are an essential part of American society. See Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 646-47, 91 5. Ct. 2125, 29 L. Ed.2d 745 (1971); see also Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 221-23, 102 5. Ct. 2382, 72 L. Ed.2d 786 (1982) (noting that public education perpetuates the political system and the economic and social advancement of state citizens). Where such institutions do not take steps to make their student body representative of the full diversity of the state's citizens, the enterprise of public education itself becomes suspect and the society's political, social and economic goals that are furthered by public education are put at risk. This risk is grave indeed where the individuals not served are those from communities against which the state once discriminated. The remnants of substantial barriers to academic achievement that the State of Michigan and the City of Detroit once imposed on African-American and Latino children continue to place such individuals at a disadvantage in the admissions process for undergraduate and graduate institutions across America. In 1971, the federal district court for the Eastern District of Michigan found that the State of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education violated the Fourteenth Amendment by maintaining a system of de jure segregation in the Detroit public schools that built on existing housing discrimination in establishing school attendance zones and busing plans. See Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. Supp. 582, 592 (E.D. Mich. -15- 1971) aff'd 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973). The Supreme Court struck down the inter-district remedy ordered by the district court to address the interdependence of school and residential segregation but did not overturn the finding of de jure discrimination. See Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 5. Ct. 3112, 41 L. Ed.2d 1069 (1974). The full scope of the discrimination identified in Bradley v. Milliken has never been remedied. Indeed, the residential racial isolation that gave rise to the initial finding of discrimination continues to characterize Detroit, which is the second most residentially-segregated metropolitan area in the United States and is home to roughly half of Michigan's population. See Sugrue Report, 5 Mich. .1. Race & L. at 276-80, 289, 292 (1999). This geographic racial isolation is reinforced by Michigan's system of public education. Id. at 289 ("The three-county Detroit area offers a particularly striking example of the lack of diversity in primary and secondary education."). The State of Michigan's historical failure to provide the full benefits of public education to its minority citizens, coupled with retrenchment in admissions of minority students to the University of Michigan and its professional schools, will cause Michigan's minority citizens to reach the same conclusion that the Supreme Court did in United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S. 717, 112 5. Ct. 2727, 120 -16- L. Ed.2d 575 (1992)—that the admissions standards of this state university are calculated to restrict access by minorities to the State's educational resources and the opportunities such resources are intended to promote. See 505 U.S. at 733-38. As taxpayers and contributors to the public funds that support the University of Michigan, Michigan~ s minority citizens will have no reason to support an elite educational institution that is not available to serve and to benefit children from their communities. Indeed, the Supreme Court has evinced a consistent commitment to the importance of equal access to government institutions especially where political participation rights are impacted. See, e.g., Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 633, 116 5. Ct. 1620, 134 L. Ed.2d 855 (1996) (state action that works to exclude particular segments of society from ordinary benefits of civic life may be invalidated). Given this commitment to access, the withdrawal of support for the university and demand for an overhaul of the university through the political and legal system by a disenfranchised community would seem to be the inevitable result of a policy that does not allow for the explicit inclusion of all members of the state. Similar demands are underway in states that already have experienced the substantial diminution of diversity in higher education admissions that plaintiffs seek to achieve. See Complaint, Rios v. Regents of the Univ. of Cal., No. C99-0525 (N.D. Cal., filed Feb. 2, 1999). -17- Those who have access to public institutions feel as if they have a greater stake in the political process. From the very beginning and throughout our history, Americans have disengaged from their government when they perceived that government as denying them full participation in public institutions. The Boston tea party, the Civil War and the urban uprisings of the last century demonstrate that alienation from the social and cultural mainstream and perceived exclusion from and inability to achieve change through the political process can have dire consequences for our social fabric. Avoiding this sense of disfranchisement is particularly critical in the area of public education, which the Supreme Court long has recognized as important for "the preparation of individuals for participation as citizens, and in the preservation of the values on which our society rests ... Ambach, 441 U.S. at 76 (citing Brown v. Board. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954). 2. Reducing the diversity of students at elite state educational institutions will harm African Americans economically, educationally, and politically. The vast majority of gains that African Americans have realized from the Civil Rights movement lie in the areas of education, employment, and political representation. See Sugrue Report, 5 Mich. .1 Race & L. at 295. African Americans who attended selective institutions of higher education have higher labor force participation, median income, and political participation. This same -18- class of people also enjoys better career opportunities and job satisfaction than their counterparts who have not attended such schools. See William G. Bowen and Derek i3ok, The Shape of the River: The Long-term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions, 119-54, 173-74 (1998). Similarly, such individuals also have significantly higher rates of civic and community involvement than their white counterparts. Id. at 156-62. By virtue of their greater income and opportunities, these individuals are in many ways the economic engine of the larger African-American community. Attrition among the ranks of such individuals will have a devastating impact on that community, both across Michigan and nationally. Access to elite public educational institutions is critical for maintaining and expanding African Americans' access to educational, political, and economic opportunities. Race-conscious admissions policies have allowed many African Americans to attend selective universities, go on to earn advanced degrees, and become active community members, business people, and political leaders: Of the more than 700 black students who would have been rejected tby selective colleges] in 1976 under a race-neutral standard, more than 225 went on to earn doctorates or degrees in law, medicine or business. Approximately 70 are now doctors and roughly 60 lawyers. Almost 125 are business executives. The average earnings of all 700 exceeds $71,000, and well over 300 are leaders of civic organizations. Bowen Report, S Mich. J. Race & L. at 435 (1999). Should the consideration of -19- race as one factor in the admissions process be prohibited, over half of the black students in selective colleges today would have been rejected.... The proportion of black students in the Top Ten law, business and medical schools would probably decline to less than 1 percent. These are the main professional schools from which most leading hospitals, law firms and corporations recruit. Id. Bowen concludes that "[t]he result of race-neutral admissions, therefore, would be to damage severely the prospects for developing a larger minority presence in the corporate and professional leadership of America." Id. As several major American corporations have noted, reducing admission of minority students to selective colleges and universities will limit their ability to develop a diverse workforce and thereby inhibit American competitiveness in the global economy. See, Brief Amicus Curiae of Steelcase, Inc. et al., Gratz v. Bollinger, No. 97-75231, Grutter v. Bollinger, No. 97-75928, available at <http://www. umich.eduf—urel/admissions/legal/gratz/amici .html> (visited May 22, 2001). States like California and Texas are still experimenting with various measures that may increase diversity at their flagship schools. Such measures involve admitting all students who graduate with grades in a specific percentage of their high school class. These measures may ameliorate the effect of eliminating race-conscious admissions on the diversity of their entering classes. Such programs do not permit universities to realize the full educational benefits -20- available from diversity because they eliminate educators' discretion to manage the diversity of their applicant pool to accomplish educational objectives. The political consequences for African Americans of reduced diversity in higher education are of still greater significance. Amici' s experiences as public officials bear out the general axiom of the American political system that communities with higher levels of political activity enjoy greater participation in the political process. As noted, education at highly selective schools is associated with higher levels of civic and political participation; however, the loss of diversity in higher education will impact not only the levels of participation necessary to achieve effective representation, but also will impact the quality of representation for citizens who are members of racial minorities. The failure to mitigate the distrust and lack of understanding fostered by geographic racial isolation Through the process of higher education also will compromise the ability of political representatives to accomplish the substantive goals of their constituents who are racial minorities. The high level of geographic racial isolation in Michigan means that higher education provides a singular opportunity for Michigan citizens to meet, live with, learn about, and learn from people of other backgrounds. Amid's experience supports research indicating that these experiences of heightened exposure and engagement with peoples of -21- different races and cultures foster an increased sense of commonality across racial and cultural lines and an elevated ability to understand the perspectives of others. See Expert Report of Patricia Gurin, Gratz v. Bollinger, Grutter v. Bollinger, S Mich. J. Race & L. 363, 399-401 (1999). A sense of commonality and receptivity is necessary for representatives such as Amici to build support in political institutions for initiatives necessary to address the matters and issues of concern to their constituents. Ignoring race as one factor in admissions would exclude the realities of entire groups of American citizens from the consciousness of those who will take over the political process, which thereby substantially disadvantages African Americans' ability to receive effective representation in the political arena. Maintaining diversity in higher education is also a compelling state interest because of its ability to increase the awareness and racial experience of white students, who will then take that experience into their legal and political careers. Access to law school is of even greater significance than access to other areas of education as a consequence of the unique entree such schools provide to the power structures of society: Lawyers do indeed occupy professional positions of responsibility and influence that impose on them duties correlative with their vital right of access to the courts. Moreover, by virtue of their professional aptitudes and natural interests, lawyers have been leaders in government throughout the history of our country. -22- In re Grffiths, 413 U.S. 717, 729, 93 5. Ct. 2851, 37 L. Ed.2d 910 (1973). Since so many of our civic and business leaders come from universities and law schools, the make-up of those groups will, of necessity, reflect the composition of those student bodies. Consequently, including the full scope of societal diversity, as well as the varied interests it represents, in the make-up of the student bodies within state colleges and professional schools is a compelling interest for each state. "The nation's future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to the ideas and mores of students as diverse as this nation of many peoples." Bakke, 438 U.S. at 313 (opinion of Powell, J.), accord Sweatt, 339 U.S. at 634. CONCLUSION Reducing or eliminating consideration of race in the admissions process for highly selective state colleges and universities will have significant negative effects on the ability of communities of color in Michigan and elsewhere to fully participate in the political and economic benefits of a society that places a premium on higher education. The provision of public education is directly linked to the creation of a politically and economically enhanced citizenry. Indeed, these goals are the fundamental rationale for providing a system of publicly-funded education. These benefits are especially obtained through undergraduate institutions such as -23- the University of Michigan and professional schools such as the University of Michigan's Law School. The decision by the state to include consideration of race in addition to other criteria for admission to the state's premier college and law school is legitimate and compelling to assure that the political and related civic benefits of education are available to all citizens of the state. Moreover, consideration of race among other factors in admissions furthers the legitimate educational goal of diversity and racial balance in the classroom. Consideration of race in admissions by such institutions is not limited to steps designed to remedy specific instances of identified discrimination. To the contrary, the Supreme Court has demonstrated that the range of permissible uses of race under the Equal Protection Clause varies with the context in which the state is acting. Specifically, a number of Supreme Court precedents, including the Court's recent line of redistricting cases, indicate that the use of race as one factor in governmental decision making is constitutionally permissible to achieve educational goals and political/civic participation, if employed to achieve educational diversity or to mitigate the effects of geographic racial isolation. For these reasons, this Court should hold that state institutions of higher education are not limited to considering race only in order to -24- remedy instances of identified discrimination and that educational diversity constitutes a compelling interest under the Fourteenth Amendment. DATED this 30th day of May, 2001. Respectfully submitted, P N GATES & ELLIS LLP au awrence Anthony R. Miles Attorneys for Amici Curiae, The Honorable John Conyers, Jr., The Honorable Carol ynC heeks Kilpatrick, The Honorable Kwame M. Kil patrick, The Honorable Dennis W. Arc her, and Saul A. Green, Esq. . -25- CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE Pursuant to FRAP 32(a) and 6 Cir. 32(a), the undersigned certifies that this complies with the type-volume limitations of FRAP 32(a)(7)(C). 1. Exclusive of the portions of the brief exempted by 6 Cir. 32(a)(7)(B)(iii), the brief contains 5455 words. 2. This brief has been prepared in proportionately spaced typeface using Microsoft Word 2000 in Times New Roman 14 point type. 3. If the Court so requested, the undersigned will provide an electronic version of the brief and/or a copy of the work or line printout. 4. The undersigned understands that a material misrepresentation in completing this certificate, or circumvention of the type-volume limits in 6 Cir. 32(a)(7) may result in the Court's striking the brief and imposing sanctions against the person signing the brief. Anthon~R. iles APPENDIX Appendix INDIVIDUAL STATEMENTS OF INTEREST OF A MI CI: THE HONORABLE JOHN CONVERS, JR.; THE HONORABLE CAROLYN CHEEKS KILPATRICK; THE HONORABLE KWAME M. KILPATRICK; THE HONORABLE DENNIS W. ARCHER; AND SAUL A. GREEN, ESQ. Honorable John Convers, Jr. Representative Conyers is serving his 19th term in the U.S. House of Representatives, having won 93 percent of the vote in Michigan's Fourteenth Congressional District. Mr. Conyers is the second most senior member of the House and is the Democratic leader on the House Judiciary Committee, where he oversees constitutional, consumer protection and civil rights issues. Throughout Mr. Conyers' terms as the congressional representative of Michigan's Fourteenth Congressional District, he has continually worked to defend and promote the interests of not only his own constituents, but of underrepresented citizens nationwide. He introduced legislation to make the prosecution of Hate Crimes easier, the Violence Against Women Act, and was critical in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1991. He has sponsored numerous bills to increase police and government accountability, and has advocated for increased voter participation. Mr. Conyers grew up attending Detroit public schools, and went on to earn a BA and then a law degree at Wayne State University. As a product of then segregated Detroit public schools, Mr. Conyers grew up recognizing the critical I difference that racial integration makes in the educational arena. As a co-founder and as the recognized Dean of the Congressional Black Caucus, Mr. Conyers has continued his work to guarantee equal access to educational and civil rights to his constituents. Faced with the possibility that admission to Michigan's most prestigious law school will no longer be feasible for many members of Michigan's citizenry, Mr. Conyers believes he needs to speak out on behalf of those who will be irreparably affected by this decision. Mr. Conyers believes that the continuing presence of racial di~crimination and unequal treatment in higher education today establish the need for affirmative action in the admissions process. He believes that the intervention of this Court is necessary to avoid "a re-segregation that will intensify existing unfairness and inequality in university admissions." He seeks to avoid a result in this litigation that would set back the years of progress made in diversity at the University of Michigan and schools across the nation. Honorable Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick Congresswoman Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick is in her third term in the United States House of Representatives, serving Michigan's Fifteenth Congressional District. She is the only Michigan Democrat on the House Appropriations Committee, which authorizes spending for all levels of the federal government. As 2 a member of the Transportation and Foreign Operations Subcommittees of the Appropriations committee, Representative Kilpatrick has developed a keen understanding of America's interest in being able to work within the diversity of the global economy, as well as the importance of providing opportunity to all U.S. Citizens. During her tenure in Congress, Ms. Kilpatrick has been a leader in addressing the inequities affecting minority-owned business's ability to participate in the advertising market. Faced with a Federal Communications Commission study that demonstrated the barriers minority broadcasters face in obtaining advertising from major advertisers, Ms. Kilpatrick convened a panel of industry officials to address the issue. Her efforts to include minority business in federal advertising was a major force leading to an presidential executive order mandating practices to increase inclusion of such businesses. In addition to her work increasing opportunilies for advertising, Ms. Kilpatrick has also been active in other areas affecting minorities to participate in American society as equal citizens. To this end, she has sponsored legislation to penalize hate crimes and eliminate racial profiling at the federal level. Born and raised in Detroit, and educated at Michigan's public universities Ms. Kilpatrick has devoted herself to educating and advancing the goals and interests of the people of the State of Michigan. Ms. Kilpatrick received her 3 undergraduate degrees from Ferris State University and Western Michigan University. She subsequently received a Masters degree in education from the University of Michigan and taught in the Detroit Public Schools. Prior to being elected to Congress, Ms. Kilpatrick served for 18 years in the Michigan State House of Representatives. In addition to her experiences advocating the interests of underrepresented communities, Congresswoman Kilpatrick's experiences as a former educator and as an alumna of the University of Michigan have given her a strong appreciation for the critical importance of access to education for preparing individuals to participate fully in our national economy and political process. This understanding led her to bring a successful NASA engineering and aeronautics program to kindergarten through l2th~grade students in her district. In addition to understanding the importance of bolstering the programs available to develop skills among primary and secondary school students, Congresswoman Kilpatrick is highly sensitive to the importance of maintaining access to higher educational institutions for minority students. For this reason, Ms. Kilpatrick takes a keen interest in maintaining the progress that the University of Michigan has made in diversifying its undergraduate body. As a former educator and as a politician, Ms. Kilpatrick understands and appreciates the benefits of education in diverse settings and wishes to assist the University of Michigan in 4 securing these educational benefits to its students, so that her constituents will be able to be represented effectively by other graduates of that institution in the future. Honorable Kwame M. Kilpatrick Mr. Kilpatrick comes from a family dedicated to civic service and community support. The son of Congresswoman Carolyn Cheeks-Kilpatrick and Wayne County Executive's Chief of Staff Bernard Kilpatrick, Mr. Kilpatrick credits his family with teaching him the value of political involvement. Mr. Kilpatrick was the youngest member elected to the 89th Legislature of the Michigan House of Representatives, and is currently the youngest member and first African-American ever elected to serve as the leader for the Democratic Caucus. Mr. Kilpatrick is committed to serving his constituents and improving their quality of life through his office. He has introduced environmental, educational and privacy bills to the Michigan House in pursuit this goal. Kwame Kilpatrick is a lifetime resident of the City of Detroit, who attended Detroit public schools and received his juris doctor from Michigan State University. Having recently graduated from law school, Mr. Kilpatrick supports the maintenance of the highly diverse and racially integrated Michigan law schools 5 that he attended. He is a f~rmer teacher, who witnessed the obstacles that students in Detroit's urban schools face, and is concerned that future Detroit residents have the same opportunities that he did to effect political change through legal and political careers. Mr. Kilpatrick believes that these opportunities are far more secure under Michigan's current inclusive admission standards than they would be were Michigan schools forced to restrict their admissions by eliminating race from the range of criteria considered for each applicant. Honorable Dennis W. Archer Dennis Archer has served as the Mayor of Detroit since January 1, 1994. In November of 1997, he was re-elected by 83 percent of the voting population. Mayor Archer is committed to improving the quality of life for the citizens of Detroit. Under his administration, the crime rate has steadily decreased each year, the downtown area has renewed itself from being nearly abandoned to being a central business district, and Mayor Archer has attracted over $13 billion in investment since taking office. Dubbed Public Official of the Year in 2000 by Governing Magazine, 1998 Newsmaker of the Year by Engineering News-Record Magazine, one of the 100 Most Powerful Attorneys in the United States by National Law Journal and one of the 100 Most Influential Black Americans by Ebony Magazine, Mayor Archer has 6 received substantial public recognition for his achievements in renewing the name of Detroit and improving the quality of life of its residents. Dennis Archer has devoted his life to the people of the State of Michigan. Born in Detroit in 1942, Mayor Archer has developed a distinguished record of public service in law and education since receiving a B.S. Degree in education from Western Michigan University. As a former teacher of learning disabled students from Detroit Public Schools, Mayor Archer is committed to educational access for all students, and has devoted himself to securing the benefits that education provides. He earned his juris doctor from the Detroit College of Law in 1970 and 'went on to practice as a trial lawyer and to teach at the Detroit College of Law and at Wayne State University Law School. He served as an Associate Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court from 1985 to 1994. Mayor Archer understands that educational access is a critical gateway to political and social benefits reserved largely to those who attend institutions of higher learning. His own commitment to education and equal access to educational facilities has afforded residents of the City of Detroit the national recognition that comes with the steady improvement in quality of life that has characterized Mayor Archer's administration. Mayor Archer strongly believes that closing that gateway to future Michigan students would not only harm those individuals, but would harm the City of Detroit and the entire state of Michigan. 7 Saul A. Green. Esq. Mr. Green is the former presidentially-appointed United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan and served in numerous positions of public trust before that post. In addition to his former public offices, Mr. Green has devoted himself to serving the people of southeastern Michigan in various ways. He is a former member of the Attorney General's Advisory Committee, and the Chair for the AGAC Violent Crime/Organized Crime Subcommittee. Mr. Gr&en is a CoChair for the Michigan Alliance Against Hate Crimes (MIAAHC). After graduating from the University of Michigan Law School in 1972, Mr. Green went on to pursue a legal career including serving as an Assistant United States Attorney, Chief Counsel, United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, Detroit Field Office and as Wayne County Corporation Counsel. As United States Attorney, he was chief federal law enforcement officer for the Eastern District of Michigan from March 1 994until May of 2001. Mr. Green has long been committed to forging societal equality in Michigan: he chaired the State Bar Committee on the Expansion of Under-Represented Groups in the Law, Co-chaired the State Bar Task Force on Racial/Ethnic and Gender Issues in the Courts and the Legal Profession, and is a Fellow of the State Bar Foundation and the American Bar Association Foundation. 8 As a result of his dedication, Mr. Green received the Wolverine Bar Association "Trailblazer Award," the State Bar of Michigan Champion of Justice Award, and in 1990 he was appointed by the Michigan Supreme Court to the Attorney Grievance commission. Mr. Green is a life-long resident of the City of Detroit, and is an active volunteer on behalf of the University of Michigan. He currently serves as President of the Alumni Association and has served on its Board of Directors and , numerous committees. His interest in maintaining the culturally and racially diverse student body that benefited himself and countless other Alumni cannot be overstated. 9 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that, on this 30th day of May, 2001, pursuant to FRAP 25 and 6 Cir. R. 31, 1 caused the foregoing Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae to be filed, by Federal Express, with: Mr. Bryant Crutcher, Office of the Clerk U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, Potter Stewart U.S. Courthouse 100 E. Fifth Street Cincinnati, OH 45202-3988 I further certify that, on the same day and pursuant to the same provisions, I caused a copy of the above motion and brief to be served, by Federal Express, on: Philip J. Kessler, P1592 1 Leonard M. Niehoff, P36695 BUTZEL LONG 350 South Main Street, Suite 300 Ann Arbor, MI 48104 John H. Pickering John Payton David F. Herr, Esq. Kirk O.Kolbo,Esq. MALSON, EDLEMAN, BRAND 300 Norwest Center 90 South Seventh Street Minneapolis, MN 55402 BORMAN & Stuart F. Delery Craig Goldblatt Brigida Benitez WILMER, CUTLER & 2445 M Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20037 Kerry L. 20300 Superior Street Morgan, Esq. Taylor, MI 48180 PENTIUK, COUVREUR ,& KOBILJAK Suite 230, Superior Place PICKERIN G Michael E. Rosman, Esq. Hans F. Bader, Esq. CENTER FOR INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS 1233 20th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 George B. Washington Esq. Eileen R. Scheff, Esq. Miranda K.S. Massie, Esq. One Kennedy Square, Suite 2137 Detroit, MI 48226 , Paul J. Lawrence PRESTON GATES & ELLIS LLP 701 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5000 Seattle, WA 98 104-7078 -2 - p~ARM~ARMOCE 01105130