Kelim: Broken Chairs and Beds

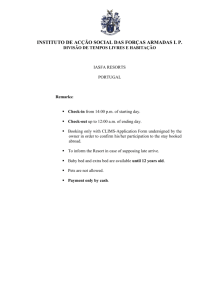

advertisement