teaching module - East

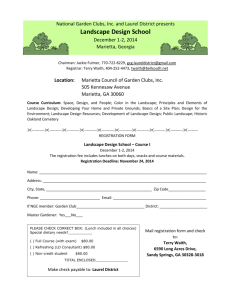

advertisement

Yu Liu: Teaching Module on the Aesthetics of China and the West 1. General Objective: To examine the original contrast and the relatively recent convergence of the West and China in art theory and practice and to explore thereby the complex issue of identity and distinction in any comparative study. 2. Specific Organization: a) Part I: the contrast of theory In the European model, for instance, the artist is conceptualized as a godlike figure who has the power to create order out of chaos and whose artistic skill is in fact measured in terms of this externally imposed form or order. In the Chinese model, in contrast, the artist is envisioned as someone who works in accordance with nature and the highest achievement in art is thought of as perfect union with nature (tian ren he yi). Reading assignments on European art: Plato, Timeus, The Bible (Genesis), Vitruvius, excerpts from Ten Books on Architecture, and Andrea Palladio, excerpts from Four Books on Architecture. Reading assignments on Chinese art: Laozi, Dao De Jing, Confucius, Analects, and Focusing the Familiar or Doctrine of the Mean (especially about the love of natural landscapes, the idea of harmonious disagreement, he er bu tong, and the notion of unity of heaven and humanity, tian ren he yi), The Book of Changes (especially parts of the ten wings supposedly written by Confucius), and Ji Cheng, The Craft of Gardens (17th century). b) Part II: the contrast of practice (example) Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and his landscape paintings: Landscape with Hagar and the Angel, 1646 Landscape with Dancing Figures, 1648 Landscape with Acis and Galatea, 1657 Landscape with Apollo and Mercury, 1660 Note: Studies of Claude’s landscape paintings will be focused on not only his use of the allusion to a by-gone classical golden age to celebrate the land possession and power of the new Church-connected Roman aristocracy, but also his geometrical and mathematical division of visual space and his use of the Euclidian single perspective to achieve the overwhelming effect of awe and shock all at once. Reading assignment: Villas and Gardens in Early Modern Italy and France, ed. Mirka Benes and Dianne Harris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). Song dynasty landscape painting (960–1279): Guan Tong (c. 906-960): Zhang Dai-qin’s forgery of Guan Tong's Drinking and singing at the foot of a precipitous mountain 1 Li Cheng (919-967): Buddhist Temple in Mountain 晴峦萧寺, 960 Fan Kuan (990-1020): Travelers amid Mountains and Streams 谿山行旅, (date ?) Guo Xi (1020-1090): Early Spring, 1072 Note: Studies of the landscape paintings of the Song dynasty will be focused on not only the so-called cartography of empire and Confucian cosmology, but also the use of multiple points of view and the spectator’s participatory excursion in the depicted landscape to engender the excitement of discovery and self discovery. Reading assignment: Steve Goldberg, “Philosophical Reflection and Visual Art in Traditional China,” in Asian Texts-Asian Contexts: Encountering the Philosophies and Religions of Asia, ed. David Jones and Ellen Klein (Albany: SUNY Press, 2010), 227240. c) Part III: an instance of the relatively recent convergence The particular moment in history is late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and the event is the sudden and dramatic turn of English landscaping from the regularity and discipline of classical art to the irregularity and freedom of nature. Studies will be made of the interconnected lives of four people: William Kent (16851742), Robert Castell (d. 1728), Matteo Ripa, and Richard Boyle, third Earl of Burlington (1695-1753). Kent was famous for his garden innovations in the late 1720s and early 1730s at Chiswick, Stowe, Rousham, Claremont, and so on where he made twisting and turning rivers and lakes and zigzagging pathways and transformed the experience of seeing a garden from the traditional single perspective or bird’s-eye view from outside the garden to the new moving and changing perspective inside the garden that emphasized the excitement of surprise. In 1728, Castell published a highly unconventional annotated translation of Pliny’s letters about his Tuscan and Laurentian country houses (Villas of the Ancients Illustrated) in which he compared the classical European garden design to the Chinese plan and cited both as in favor of natural irregularity. Matteo Ripa was a European missionary-artist and worked for a long time at the imperial court of Kangxi. While there, he made thirty-six engravings of the emperor’s summer resort at Chengde in 1713. In 1724, during a visit to London, he made these engravings available to Burlington. Burlington was a close friend and/or patron of Kent and Castell; as such, he helps us understand why the English garden was called in the 18th century le jardin anglochinois and why this is not just because Sir William Chambers built a House of Confucius and a Chinese pagoda at Kew Garden. Reading Assignments: Robert Castell, The Villas of the Ancients Illustrated (London, 1728). John Charlton, A History and Description of Chiswick House and Gardens (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1958). Basil Gray, “Lord Burlington and Father Ripa’s Chinese Engravings,” The British Museum Quarterly, 22 (1960): 40-43. 2 Yu Liu, “Castell’s Pliny: Rewriting the Past for the Present,” Eighteenth Century Studies, 43 (2010): 243-257. Yu Liu, Seeds of a Different Eden: Chinese Gardening Ideas and a New English Aesthetic Ideal (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2008). Michael I. Wilson, William Kent: Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685-1748 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984). Finally, it will be interesting to read English literary works such as Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads and The Prelude and Shelley’s poems “Mont Blanc” and “Ode to Intellectual Beauty” and see the then already thoroughly English affinity with nature. Even though we do not have to connect this new English or Western sentiment about nature with the earlier transmission of Chinese gardening ideas, any effort to do this will reward us with a significantly different understanding of the involved history of ideas and the complex issue of identity and distinction in any comparative study of China and the West. 3. Evaluation methods: A combination of tests and research essays. 3