III Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. J. Kochanowskiego w Krakowie 1

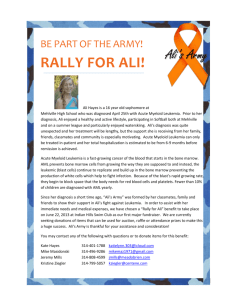

advertisement