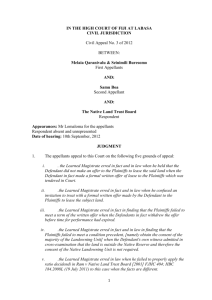

Takings 10 Penn Central

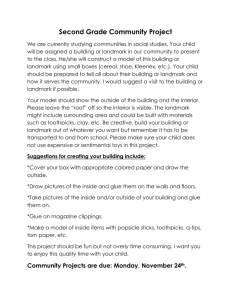

advertisement