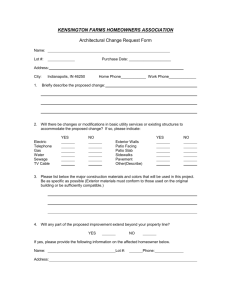

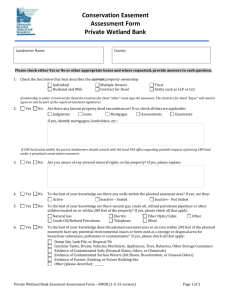

Property

advertisement