The Brown Berets interview

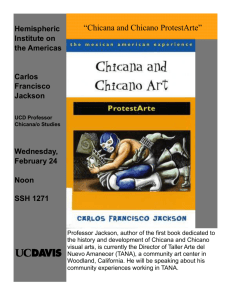

advertisement

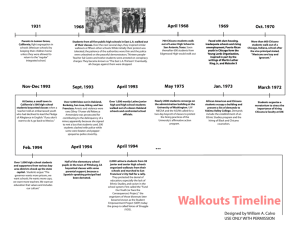

The Brown Berets: Young Chicano Revolutionaries Fight Back! interviewed Carlos Montes, one of the founders and former Minister of Information of the Brown Berets National Office in East Los Angeles from 1967 to 1970. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Brown Berets emerged as one of the most powerful and militant organizations in the Chicano liberation movement. Like the Black Panther Party, the Brown Berets were hit hard by government repression. This interview brings out a part of our history that is rarely taught in schools and some lessons for today’s activists from our movement’s past. Fight Back!: Who were the Brown Berets? Carlos Montes was a co-founder of the Brown Berets in 1967. Carlos Montes: We were a group of young Chicano revolutionaries from the barrios of the Southwest fighting for the self-determination of our people. We organized in our barrios, published the newspaper La Causa, ran a free clinic and fought against police brutality as well as against the U.S. war in Vietnam. We evolved from a youth group - from Young Citizens for Community Action, to Young Chicanos for Community Action to the Brown Berets. We evolved from civic participation and assimilation to revolutionary nationalism. The brown beret was a symbol of the pride in our culture, race and history. It also symbolized our anger and militancy and fight against the long history of injustice against the Chican@ people in the U.S., especially the Southwest. We claimed the Southwest as Aztlan, the original homeland of the indigenous Aztec ancestors and founders of Mexico City…We were from poor working class families growing up with the racism and police abuse. 1 Fight Back!: Why did you join? Carlos Montes: My family came to L.A. from Juarez, Mexico in 1956. I grew up in the barrios of South L.A. and East L.A. and experienced the racist conditions in the schools, police abuse, drugs, and the poor living conditions. This led me to get involved in the first Chicano student group, the Mexican American Student Association (MASA), at East L.A. College in 1967 which saw using education as the solution to injustice. I was also working as a youth center director and came across Young Chicanos for Community Action and La Raza newspaper, which were starting to voice opposition to the racist conditions in the barrio. I was drawn to the more active and direct action approach of Young Chicanos for Community Action, which became the Brown Berets in late 1967. Fight Back!: What kind of community organizing did you do? Carlos Montes: We first took on the issue of police brutality. The East L.A. sheriffs were notorious for their brutality, especially against Chicano youth, which I experienced cruising Whittier Boulevard on the weekends with hundreds of other youth. We were the first to lead a protest at the East L.A. sheriffs station to protest the killing of youth at the station in 1967. We also started working with the car clubs in East L.A. to defend them against police abuse. We opened a local cultural center in East L.A., The Piranya Coffee House, where we held youth meetings and cultural programs. It became one of the meeting places for the Brown Berets. We also started working on the problems of the bad school conditions and the racist educational system. Our schools were old and in bad condition, with high drop out, or push out, rates and racist administrators and teachers. Over time, we started agitating for bilingual education, better school conditions, Chicano studies and more Chicano teachers. We attended community, school and youth meetings to raise demands for better educational and school conditions. This finally led to the historic East L.A. Blowouts in March of 1968, where thousands of high school Chicano youth walked out of the four predominantly Chicano high schools in the Eastside over a two week period. Police photo of Brown Beret led walk-out at L.A.’s Lincoln High School 2 The Brown Berets were the first to run in to the high schools, yelling, “Walk out! Walk out!” To get the blowouts started, me and James Vigil (a k a Mangas Coloradas) ran into Lincoln High School on the first day to kick off the walkouts. We then went on to Roosevelt High School and the other schools. We also supported the land movement in New Mexico of the Chicano small farmers and ranchers. They fought to recover the land stolen by the rich Anglo ranchers and the U.S. federal government. We supported the United Farm Workers’ struggle for union recognition and better working conditions. We marched with the first Rainbow Coalition in the Poor Peoples Campaign in Washington D.C. in the summer of 1968. We were at the first historic Chicano Youth Liberation conference, where the Plan Espiritaul de Aztlan was formulated in Denver, Colorado. We also organized the first Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War in December 1969. This led to the historic national Chicano Moratorium march and rally against the Vietnam war on Aug. 29, 1970, where over 20,000 Chicanos protested the high casualty rate of Chicanos in Vietnam and demanded self-determination at home in the Southwest. ‘Raza si! Guerra no!’ Fight Back!: What were major successes? Carlos Montes: We exposed police brutality. Back then, some people tried to deny it existed. We were part of building the Chicano movement for self-determination, which raised the slogan of Chicano Power. It also started the movement for cultural awareness and pride in our Chicano history in the Southwest and Mexico, and our culture and language. The blowouts were historic because it was the fist wave of mass actions by Chicanos in the urban barrios of the late 1960s. We eventually won bilingual education, Chicano studies, better school conditions and Chicano teachers and administrators. The mass anti-war demonstrations were part of the movement that eventually forced Nixon to pull out of Vietnam. We also opened the doors for affirmative action in higher education and political representation. Fight Back!: How did the political views of the Brown Berets develop? Carlos Montes: We started out with civic involvement and education as the road to equality, but soon learned that only real revolutionary change and political power by poor working people would gain real equality and freedom. We evolved from civic duty, work within the system, to selfdetermination, revolutionary nationalism and international solidarity with the liberation movements of Latin America, Africa and Asia - like the Vietnamese, the Congolese and Cubans fighting for freedom from U.S. domination. Fight Back!: How did they see the world? Carlos Montes: We believed in self-determination for Chicanos. The Brown Berets’ thirteen-point political program talked about self-determination as having political and economic control over our lives. It called for a return of our land, release of prisoners, jobs, education, housing, an end to the destruction of the environment by the capitalists, open borders, solidarity with all revolutionary peoples engaged in the struggle for self-determination. And we denounced the U.S. system of capitalism and imperialism. 3 Fight Back!: Did they work with groups in the Black community? Carlos Montes: Yes, we supported and formed alliances with Black groups such as the Black Panther Party. We supported them when the police attacked them. We also set up similar programs like the East L.A. Free Clinic and free breakfast programs. We also were part of the first Rainbow Coalition when we joined the Poor Peoples Campaign in the summer of 1968. The Rev. Martin Luther King had struggled within the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to include the Chicano militant groups in the march on Washington, such as the Crusade for Justice, from Colorado; Alliance of Free City States, from New Mexico and the Brown Berets. Fight Back!: What happened to the Brown Berets? Carlos Montes: The Brown Berets grew to have about fourteen chapters throughout the Southwest, with East L.A. being the National Office. After the initial organizing efforts, the Los Angeles Police Department and sheriffs sent undercover officers to infiltrate the Brown Berets. The police infiltrators spied and acted as agent provocateurs, with the purpose of arresting the leadership and disrupting the organization. The police used secret grand jury indictments to try to jail and tie up the leadership in court trials. The top-down military structure of the group did not allow for the development of new leadership, or the leadership and development of the women who did a lot of the internal work. The Brown Berets continued ‘till about 1972, when they were disbanded. By then, the Prime Minister David Sanchez had degenerated into staging publicity stunts and running a one-man egomaniac undemocratic group. Fight Back!: What are the lessons for today? Carlos Montes: Building a mass militant movement to the stop the U.S. war drive, for social change and for revolution is key. Also rebuilding grassroots militant organizations in the community that fight for self-determination, social justice and liberation - not just for reforms. We need an organization that includes the participation of the entire family and that values and promotes the leadership of women. Fight Back!: What about today’s ‘Brown Berets?’ Carlos Montes: The current group that call themselves Brown Berets have not led or been involved in any positive mass campaigns for self-determination or social change. They have not been able to grow or get support from any large segments of the Chicano community. They have not taken up the fight for immigrant rights or other important issues, especially the growing anti-war movement of today. They are primarily male and male dominated. They use militant rhetoric, but do not organize. To talk with Carlos Montes contact him at the Centro CSO (323) 221-4000 http://www.fightbacknews.org/2003winter/brownberets.htm 4