Mister Republican - Mississippi Press Association

advertisement

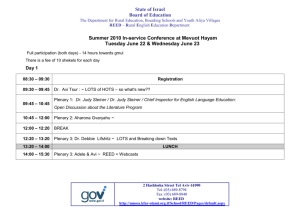

3246 Words Mister Republican People laughed when Clarke Reed first preached the GOP gospel. Then he helped elect presidents. Guess who's laughing now. With Photo: REAGAN Former state GOP chairman Clarke Reed with former President Ronald Reagan. Photo Courtesy of Clarke Reed. With Photo: BUSH Former state GOP chairman Clarke Reed with former President George Bush at the White House. Photo Courtesy of Clarke Reed. With Photo: REED Clarke Reed in his Greenville office in April. Photo By Maggie Day. By MACEY BAIRD Summer 1975 A tall, thin man in his prime strides into Doe’s Steak House and ambles through the kitchen holding two paper sacks. The cooks fuss over him and a trail of greetings follows: “There’s Clarke, how’s it going Clarke, who you eating with tonight Clarke?” He shakes some hands and walks over to his table, setting bottles of whiskey and wine on the plastic tablecloth and greeting his party. Tonight, it is a Delta Council executive. Last week, it was a New York Times reporter. Long after his political prominence has begun to wane, Clarke Reed is still hosting at the rambling house with the great steaks, entertaining his crowd with spirits and wry, self-deprecating humor. On this warm March evening, the old raconteur once again makes his way through the sea of women. There’s still the trademark patrician posture, but now he shuffles with a walker, a reminder of last summer’s nightmarish car crash that crushed his hip and pelvis. He squeezes through the clutter of misshapen tables until he reaches his party and deposits two brown bags on the table: a bottle of red wine and a bottle of white. It’s time to woo again. He’s in classic Clarke mode. Reed, 82, is the father of the modern Mississippi Republican Party, the man credited with helping to eliminate the “Mississippi Democrat” and create a two-party system in the state. For the past 60 years, Reed has been a guiding hand for Republicans, helping steer Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy” and subsequent victory, then helping maneuver the party through the Watergate scandal and the Gerald FordRonald Reagan battle. Sitting here, Reed looks like just another native you’d see down at Buck’s or maybe a Rotary Club luncheon at the country club -- khakis and a patterned sweater, long and lanky, white hair pieced across his crown, sharp eyes and a sharp wit to match. But Reed has been to a state dinner at the White House. He’s had direct access to governors and presidents. When Nixon was in office, the phrase “Clear it with Clarke” became routine among staff regarding Southern matters. Before Reed and his gang stepped in during the mid-’60s, the Republican Party was virtually invisible in Mississippi and much of the rest of the South. Reed played a major role in changing that. “There were two cataclysmic changes in American history,” Reed says. “One was the Civil War. The other was the South coming back into the system.” Reed believes both changed unnatural alliances and that the latter is the closest thing since the War Between the States to alter the country’s political structure. It was the first time the South had fully been part of the system. Now he leans into the conversation, weathered hands grasping a simple wooden chair in his sparse Reed-Joseph International office, and gears up to tell a story he’s told a hundred times -- the story of a young band of brothers who catapulted the South back into national political prominence. He began with an inexperienced generation, gathering kids such as Lanny Griffith and Roger Wicker from the Young Republicans chapter at Ole Miss and developing a group strong enough to contend with the Democrats, long the dominant political organization in the South. “They could see clearly what to do. So we’re young. We may just have to outgrow everybody,” Reed says. As he sees it, Mississippi used to be essentially a no-party state. It was made up of “Mississippi Democrats,” people who wouldn’t fully align themselves with the national Democrats, Reed says of his rival party. Reed believed that the conservative values and culture of these same Mississippians aligned with the Republican Party. He became a prophet in that regard. “They would say, we’re not Democrats. We’re Mississippi Democrats, we’re above both parties,” Reed says. “And I made my argument, let’s change parties, let’s get a two-party system going, see? I started teaching high school civics to people.” Mike Retzer, former chairman of the Mississippi Republican Party and ambassador to Tanzania, says tenacity comes to mind whenever he thinks of his onetime mentor. “He’s messing with the Republican Party in 1960 and everyone was just wacko to be in the Republican Party,” Retzer says. “People thought, what's the point? You're not going to elect anyone.” Reed retains the same old tenacity today, though he’s stiff from his injuries and barely budges but to uncross his rangy legs and fresh New Balance shoes. He speaks in his trademark Clarke mumble, often having to repeat himself to someone whose ears aren’t accustomed to it. He talks of this time in an automatic onslaught of recount. He’s been repeating his story for four decades. He labels the 1972 election of Thad Cochran and Trent Lott to Congress as a “quantum leap” for the GOP in Mississippi. “We started with young people who didn’t have a stake in the system as much,” Reed says. He answers a question about the youth of the early party before trailing off midsentence and coming back to explain the state’s warped political pairings. It’s a habit of his, these half-finished sentences. You can see him reconstructing the time in his head, bouncing from one story to another because he’s thought of a different point he wants to make. Reed found his own unnatural alliance in Hodding Carter III, editor of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Delta Democrat-Times in Greenville and later State Department spokesman for the Jimmy Carter administration, whose political views stretched miles from Reed’s own. With Hodding Carter constantly on television during the Iranian hostage crisis and Reed frequently called upon to explain the Republican resurgence in the South, the two became the best-known Greenvillians of their era. “It is hard to overstate his importance. He came relatively early, stayed late and was a consistent exponent of consistent party-building, human as well as financial,” Carter says. “He tied the state effort to the national party and eliminated the prefixes.” “Hodding and I worked together, more or less,” Reed says. “He wanted a real Democratic Party and it wasn’t really there. We wanted the same thing, just different parties.” Reed doesn’t find it odd that a liberal newspaperman and a conservative political leader could work together for the good of their constituents. He’s matter-of-fact about it, stirring nostalgia for a more idealistic time when good and evil weren’t so clearly divided down political lines. Reed gives credit to Carter and his crew at the paper for helping spread the importance of bipartisanship in the state. “If he hadn’t been here I might not have been all that you see. He said there’s a twoparty system, here’s what happens you see,” Reed says. “They played up everything we did so we looked good, saying we’re really doing something.” “(Reed’s) the best conjure man I've ever known,” Carter says. “He gives the impression of a man mumbling his way through success by accident.” “He is, of course, a highly focused political animal who never lost sight of his objective. He is living proof of that old saw about the natural superiority of Southern politicians, save that he saw his role as building rather than running.” A friendship evolved that transcended civic duties and political ideologies. “It was a historic time. A lot of fun, too,” Reed says, tilting forward in a conspiratorial laugh. “I’d have him to my events and he’d run with my conservative crowd.” You get a glimpse of the good old boy Reed is in moments like this. He’s the image of the classic Delta rascal: a whiskey-drinking businessman who can charm both company and caucus. His wife, Judy, is out of town this week, so he’s spent every lunch at Jim’s Café on Washington Avenue with the other good old boys around the county. The men sit at the center table in crisp button-downs and thinning hair, chairs pushed back and legs crossed. They’re all long on opinion and short on subtlety, chatting about everything but the weather while they pick at the remnants of the owner’s burgers drenched in Gus Johnson’s famous hot sauce. Reed’s known for his social skills and loved for his charisma, something he passed down to his daughter Julia. She’s the author of two books and a contributing writer at both Vogue and Newsweek. Her irreverent humor has won the readership of many, and Julia often places her father as a central character in her stories, from his being so particular about her dress to his and his friends’ social status. In Julia’s first book, "Queen of the Turtle Derby," she devotes a chapter to the “shonuff” man.” Clarke Reed’s longtime friend and former business partner, the late Barthell Joseph, coined this term about the ideal Southern man. As Julia describes it, Joseph said this is a “man who’ll step up to the plate,” a man strongly committed to a certain set of values. To see if this is a Southern gentleman who can live up to the Southern woman, Joseph asks a series of questions, ranging from game-time decisions to relationships to tithing in the church. As Julia describes it, it’s her dad. He helped pull a party from state obscurity and pushed it to a place of political influence. He held parties at his office at the foot of the levee on Saturday and then sat in a pew on Sunday. You’d expect to see remnants of these memories plastered across the walls in Reed’s office. There should be pictures of Reed with more hair, grinning with those prestigious powerhouses who helped run the party. There should be photos of drinks with the boys and framed clippings of Reed’s successes. Instead, it resembles a bachelor pad. There is instead a simple conference room and a spartan cubicle that Reed holds at Reed-Joseph International, a Greenville-based company that specializes in bird and wildlife control. There’s nothing to hint at the power and influence he has willingly wielded for so many years. It’s in keeping with his self-enforced humility. Reed cast his first stone in the Republican pool by voting for Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 and played a part in Barry Goldwater's run in 1964. But it all really began for Reed in 1966 when Wirt Yerger resigned as chairman of the Mississippi Republican Party and Reed was thrown into the position, the second one in the party’s history. Shortly after, he became chairman of the Southern Republican Chairmen's Association — “We were young guys with no ax to grind,” Reed says — an organization instrumental in constructing Nixon’s “Southern strategy” that put him and the other chairmen into power. “We gave it extra attention; we said we want you,” says Reed, who called himself “the unknown chairman” at the time. “We’d been out of things so much.” “I remember seeing a license tag that said: ‘Put your heart in the heart of Dixie or put your back on the back of a jackass and get out,’ ” Reed says. “That kind of attitude. And that would change it. And he (Nixon) helped change it, see?” Nixon was generous to those who elevated him to the Oval Office, extending an open hand to the Southern chairmen. “He let us put people in the administration. We had access so to speak,” Reed says. “We could always make contact and talk to him about whatever we wanted to do.” Retzer recalls the last White House wedding, when Tricia Nixon was married. He recalls breaking into laughter when he saw pictures of the party. “Clarke’s in the pictures,” Retzer says. “It’s like Clarke’s in the wedding party.” Reed never ran for office. He was content to pull strings behind the curtain and train his disciples to preach the fundamentals of the party he helped shape below the Mason-Dixon line. Retzer witnessed the considerable impact Reed can have in Congress. “Postcard voter registration got to be a hot issue. He wasn’t in favor of that,” Retzer says. “But the leadership had signed off on it. Clarke got on the phone in a weekend and turned that back in a hurry.” Retzer finds humor in Reed’s persistence and notes this is what makes him effective. “He will call and call and call,” Retzer says. “He will bother the issue until the issue gets solved. That's really a great strength.” Reed’s daughter agrees. Julia says he raised “every dime of (Gov.) Kirk Fordice’s winning war chest” through what she calls castigation, which happens to be one of Clarke’s favorite words. “My mother always freaks out when she hears him on the phone raising money,” Julia says. “He basically insults people into giving him money, as in, ‘This is too important, this is bigger than you, how can you live with yourself if you don't write that check.’ ” Julia’s mother, Judy, has been with Clarke in every election, hosting parties and contributing Southern charm to move her husband’s agenda. She and her social skills – and her devotion to charity and the arts – are legend in Greenville. This year, the Greenville Arts Council gave her an award for her “lifetime contribution to the arts.” “My mother was a really big part of the prestige you mention,” Julia says. “She tirelessly entertained, usually at the drop of a hat.” She remembers how, in the early 1970s, Clarke mentioned that famed conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. and his wife, Pat, were coming to dinner in two days. Because the house was in the midst of remodeling, Judy had to repaint and put the door frames back on all the doors and re-hang the curtains. She bought a bunch of wicker for outdoor tables with staple-gun makeshift cushions. To Julia, it seems this is the kind of story that epitomizes her parents, whom she often refers to as “Daddy” and “Mama.” “Buckley played the piano well into the night and Pat wrote my mother for her scalloped oyster recipe. My mother's best friend named that menu ‘The V.D. Dinner’ for Visiting Dignitary,” Julia says. “She went on to make it for Ronald and Nancy Reagan, Elliott Richardson (Nixon's attorney general) and countless others.” Retzer says he got his foot in the GOP door by translating for Reed. “I traveled around with him,” Retzer says. “I always said I was his translator because he’d give his speech and then I'd get up and repeat what he said.” Retzer laughs. He remembers another time when he was 28, sitting in Reed’s office when Nixon’s chief of staff called him and offered a seat on the World Bank. “He said, ‘Uh no, no, I don’t want that,’ ” Retzer says, imitating Reed’s rapid-fire Southern mumble. “Then he said, ‘Well, I’m sitting here with Retzer. Mike, you want to be on the World Bank?’ ” “They never could do anything for Clarke in terms of giving him anything because he just wanted people to do right.” Sometimes, this resoluteness seeped into his politics, like the storied split of the Republican Party in the 1976 battle over presidential nominees Reagan and Ford. Reed, who sided with Ford during the convention, said he was originally for Reagan before the former California governor picked as his running mate Sen. Richard Schweiker from Pennsylvania. Schweiker's “swagger was terrible,” Reed said. “The vice president should be the nearest thing to a cloned twin. When I heard he (Reagan) did this, I said I did not trust him.” Reed's switch led to drama at the convention in Madison Square Garden. At a critical moment, when the Reed-led Mississippi delegation and its 30 votes went solidly against a rules change that Reagan wanted, it was a clear signal that Reagan was bound to lose. Ford won the nomination but lost the election to Jimmy Carter. When Reagan became president four years later, some say Reed was boxed out. Reed says it’s not so. He waves off the idea that he was isolated because of his past alignment and says, “No, he was good to me. We had some meals together.” Reed likes to tell stories. His comments are candid, his topics bounce from date to date, person to person, in one breath. In 150 minutes of talking, he hasn’t glanced at his watch. He likes to talk; that’s how he’s gotten things done. Retzer remembers the Southern Republican Leadership Conference in Houston before the 1972 National Republican Convention when Reed sat down with Ford campaign chairman Bo Callaway and told him Nelson Rockefeller, Ford’s vice president, couldn’t be his running mate in the 1976 election. “He said listen, Rockefeller just isn’t going to sell in the South,” Retzer said. “You guys can forget that.” Callaway immediately pulled Rockefeller aside before he spoke at the conference and told him the news. “After he addressed the crowd, he had the band play 'Mississippi Mud,' some reference to Clarke,” Retzer says and laughs. “See, it wasn’t public knowledge yet.” Retzer says Reed thought it was funny; it didn’t bother him. After Hurricane Camille in 1969, Reed persuaded Nixon and company to stop in Mississippi on a trip back to Washington. Though Nixon initially refused, Reed finally contacted the right person who sold the detour. It was the first presidential visit to Mississippi since Theodore Roosevelt’s bear hunt in 1902. “He landed, and we’ve been so out of the thing, about 40,000 people showed up at the airport,” Reed says. “We looked like a bunch of homeless people because of the storm.” “A guy named Steve Bull (who) handled the advances, he said that was probably the best talk they ever made in Nixon’s career.” Reed is still active in the GOP but says he wouldn’t want to run things today. “It was a challenge then, you see. You make a little history or whatever you want to do,” Reed says. “Back then, there weren’t that many people standing in line to do it.” Now Reed’s back in his hometown, a town he loves but also one where he cannot exercise much control. The town is run by Democrats. Awhile back, the city abolished the airport commission that he once chaired. For now, Reed spends his days raising money for the GOP and helping run ReedJoseph International. True to Southern degrees of separation, Reed’s partner is the son of his former partner. And the son-in-law of Hodding Carter. Through the spring, he was in the office every day, lugging his tennis-ball-rigged walker through the obscure building on Main Street. He underwent a hip replacement in the heat of summer and looked forward to getting rid of the walker. Reed was disappointed when Gov. Haley Barbour dropped out of the race for president in April, to the surprise of many. Barbour is a Reed protégé, a man with similar wit and an appetite for political warfare. Reed found Barbour when he was a 19-year-old Ole Miss student and later plucked him from the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity house in his senior year to help with the 1968 Nixon campaign. Now he has picked up the baton and, after running the national party, is running the state. “He gets more done than I do,” Reed says in typical self-deprecating fashion. “His involvement shows how far we’ve come in the system in Mississippi.” Produced by the Meek School of Journalism and New Media at the University of Mississippi. -30-