English language

advertisement

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of

England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence

of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria. Following the economic, political,

military, scientific, cultural, and colonial influence of Great Britain and the United

Kingdom from the 18th century, via the British Empire, and of the United States since

the mid-20th century, it has been widely dispersed around the world, become the

leading language of international discourse, and has acquired use as lingua franca in

many regions. It is widely learned as a second language and used as an official

language of the European Union and many Commonwealth countries, as well as in

many world organizations. It is the third most natively spoken language in the world,

after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish.

Countries where English is an official or de facto official

language, or national language

Countries where it is an official but not primary language

Historically, English originated from the fusion of languages and dialects, now

collectively termed Old English, which were brought to the eastern coast of Great

Britain by Germanic (Anglo-Saxon) settlers by the 5th century – with the word

English being derived from the name of the Angles. A significant number of English

words are constructed based on roots from Latin, because Latin in some form was the

lingua franca of the Christian Church and of European intellectual life. The language

was further influenced by the Old Norse language due to Viking invasions in the 8th

and 9th centuries.

The Norman conquest of England in the 11th century gave rise to heavy

borrowings from Norman-French, and vocabulary and spelling conventions began to

give the superficial appearance of a close relationship with Romance languages to

what had now become Middle English. The Great Vowel Shift that began in the south

of England in the 15th century is one of the historical events that mark the emergence

of Modern English from Middle English.

Owing to the significant assimilation of various European languages throughout

history, modern English contains a very large vocabulary. The Oxford English

Dictionary lists over 250,000 distinct words, not including many technical or slang

terms, or words that belong to multiple word classes.

Significance

Modern English, sometimes described as the first global lingua franca, is the

dominant language or in some instances even the required international language of

communications, science, information technology, business, aviation, entertainment,

radio and diplomacy. Its spread beyond the British Isles began with the growth of the

British Empire, and by the late 19th century its reach was truly global. Following the

British colonization of North America, it became the dominant language in the United

States and in Canada. The growing economic and cultural influence of the US and its

status as a global superpower since World War II have significantly accelerated the

language's spread across the planet. English replaced German as the dominant

language of science Nobel Prize laureates during the second half of the 20th century

(compare the Evolution of Nobel Prizes by country).

A working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of

fields, occupations and professions such as medicine and computing; as a consequence

over a billion people speak English to at least a basic level (see English language

learning and teaching). It is one of six official languages of the United Nations.

One impact of the growth of English has been to reduce native linguistic diversity

in many parts of the world, and its influence continues to play an important role in

language attrition. Conversely the natural internal variety of English along with

creoles and pidgins have the potential to produce new distinct languages from English

over time.

History

English is a West Germanic language that originated from the Anglo-Frisian and

Old Saxon dialects brought to Britain by Germanic settlers from various parts of what

is now northwest Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands. Up to that point, in Roman

Britain the native population is assumed to have spoken the Celtic language Brythonic

alongside the acrolectal influence of Latin, from the 400-year Roman occupation.

One of these incoming Germanic tribes was the Angles, whom Bede believed to

have relocated entirely to Britain. The names 'England' (from Engla land "Land of the

Angles") and English (Old English Englisc) are derived from the name of this tribe—

but Saxons, Jutes and a range of Germanic peoples from the coasts of Frisia, Lower

Saxony, Jutland and Southern Sweden also moved to Britain in this era.

Initially, Old English was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins

of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Great Britain but one of these dialects, Late West

Saxon, eventually came to dominate, and it is in this that the poem Beowulf is written.

Old English was later transformed by two waves of invasion. The first was by

speakers of the North Germanic language branch when Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar

the Boneless started the conquering and colonisation of northern parts of the British

Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries (see Danelaw). The second was by speakers of the

Romance language Old Norman in the 11th century with the Norman conquest of

England. Norman developed into Anglo-Norman, and then Anglo-French - and

introduced a layer of words especially via the courts and government. As well as

extending the lexicon with Scandinavian and Norman words these two events also

simplified the grammar and transformed English into a borrowing language—more

than normally open to accept new words from other languages.

The linguistic shifts in English following the Norman invasion produced what is

now referred to as Middle English, with Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales

being the best known work.

Throughout all this period Latin in some form was the lingua franca of European

intellectual life, first the Medieval Latin of the Christian Church, but later the

humanist Renaissance Latin, and those that wrote or copied texts in Latin commonly

coined new terms from Latin to refer to things or concepts for which there was no

existing native English word.

Modern English, which includes the works of William Shakespeare[36] and the

King James Bible, is generally dated from about 1550, and when the United Kingdom

became a colonial power, English served as the lingua franca of the colonies of the

British Empire. In the post-colonial period, some of the newly created nations which

had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as the lingua

franca to avoid the political difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous

language above the others. As a result of the growth of the British Empire, English

was adopted in North America, India, Africa, Australia and many other regions, a

trend extended with the emergence of the United States as a superpower in the mid20th century.

Classification and related languages

The English language belongs to the Anglo-Frisian sub-group of the West

Germanic branch of the Germanic family, a member of the Indo-European languages.

Modern English is the direct descendant of Middle English, itself a direct descendant

of Old English, a descendant of Proto-Germanic. Typical of most Germanic

languages, English is characterised by the use of modal verbs, the division of verbs

into strong and weak classes, and common sound shifts from Proto-Indo-European

known as Grimm's Law. The closest living relatives of English are the Scots language

(spoken primarily in Scotland and parts of Ireland) and Frisian (spoken on the

southern fringes of the North Sea in Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany).

After Scots and Frisian come those Germanic languages that are more distantly

related: the non-Anglo-Frisian West Germanic languages (Dutch, Afrikaans, Low

German, High German), and the North Germanic languages (Swedish, Danish,

Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faroese). With the exception of Scots, none of the other

languages is mutually intelligible with English, owing in part to the divergences in

lexis, syntax, semantics, and phonology, and to the isolation afforded to the English

language by the British Isles, although some, such as Dutch, do show strong affinities

with English, especially to earlier stages of the language. Isolation has allowed

English and Scots (as well as Icelandic and Faroese) to develop independently of the

Continental Germanic languages and their influences over time.

In addition to isolation, lexical differences between English and other Germanic

languages exist due to heavy borrowing in English of words from Latin and French.

For example, we say "exit" (Latin), vs. Dutch uitgang, literally "out-going" (though

outgang survives dialectally in restricted usage) and "change" (French) vs. German

Änderung (literally "alteration, othering"); "movement" (French) vs. German

Bewegung ("be-way-ing", i.e. "proceeding along the way"); etc. Preference of one

synonym over another also causes differentiation in lexis, even where both words are

Germanic, as in English care vs. German Sorge. Both words descend from ProtoGermanic *karō and *surgō respectively, but *karō has become the dominant word in

English for "care" while in German, Dutch, and Scandinavian languages, the *surgō

root prevailed. *Surgō still survives in English, however, as sorrow.

In English, all basic grammatical particles added to nouns, verbs, adjectives, and

adverbs are Germanic. For nouns, these include the normal plural marker -s/-es, and

the possessive markers -'s and -s' . For verbs, these include the third person present

ending -s/-es (e.g. he stands/he reaches ), the present participle ending -ing, the simple

past tense and past participle ending -ed, and the formation of the English infinitive

using to (e.g. "to drive"; cf. Old English tō drīfenne). Adverbs generally receive an -ly

ending, and adjectives and adverbs are inflected for the comparative and superlative

using -er and -est (e.g. fast/faster/fastest), or through a combination with more and

most. These particles append freely to all English words regardless of origin

(tsunamis; communicates; to buccaneer; during; bizarrely) and all derive from Old

English. Even the lack or absence of affixes, known as zero or null (-Ø) affixes, derive

from endings which previously existed in Old English (usually -e, -a, -u, -o, -an, etc.),

that later weakened to -e, and have since ceased to be pronounced and spelt (e.g.

Modern English "I sing" = I sing-Ø < I singe < Old English ic singe; "we thought" =

we thought-Ø < we thoughte(n) < Old English wē þōhton).

Although

the syntax of

English

is

somewhat

different from

that of other

West Germanic

languages with

regards to the

placement and

order of verbs

(for example, "I

have never seen

anything in the

square"

=

German

Ich

habe nie etwas

auf dem Platz

gesehen,

and

the Dutch Ik

heb nooit iets

op het plein

gezien, where

the participle is

placed at the

end), English syntax continues to adhere closely to that of the North Germanic

languages, which are believed to have influenced English syntax during the Middle

English Period (e.g., Danish Jeg har aldrig set noget på torvet; Icelandic Ég hef aldrei

séð neitt á torginu). As in most Germanic languages, English adjectives usually come

before the noun they modify, even when the adjective is of Latinate origin (e.g.

medical emergency, national treasure). Also, English continues to make extensive use

of self-explaining compounds (e.g. streetcar, classroom), and nouns which serve as

modifiers (e.g. lamp post, life insurance company), a trait inherited from Old English

(See also Kenning).

The kinship with other Germanic languages can also be seen in the large amount

of cognates (e.g. Dutch zenden, German senden, English send; Dutch goud, German

Gold, English gold, etc.). It also gives rise to false friends, see for example English

time vs Norwegian time ("hour"), and differences in phonology can obscure words

that really are related (tooth vs. German Zahn; compare also Danish tand). Sometimes

both semantics and phonology are different (German Zeit ("time") is related to

English "tide", but the English word, through a transitional phase of meaning

"period"/"interval", has come primarily to mean gravitational effects on the ocean by

the moon, though the original meaning is preserved in forms like tidings and betide,

and phrases such as to tide over).[citation needed]

Many North Germanic words entered English due to the settlement of Viking

raiders and Danish invasions which began around the 9th century (see Danelaw).

Many of these words are common words, often mistaken for being native, which

shows how close-knit the relations between the English and the Scandinavian settlers

were (See below: Old Norse origins). Dutch and Low German also had a considerable

influence on English vocabulary, contributing common everyday terms and many

nautical and trading terms (See below: Dutch and Low German origins).

Finally, English has been forming compound words and affixing existing words

separately from the other Germanic languages for over 1500 years and has different

habits in that regard. For instance, abstract nouns in English may be formed from

native words by the suffixes "‑ hood", "-ship", "-dom" and "-ness". All of these have

cognate suffixes in most or all other Germanic languages, but their usage patterns

have diverged, as German "Freiheit" vs. English "freedom" (the suffix "-heit" being

cognate of English "-hood", while English "-dom" is cognate with German "-tum").

The Germanic languages Icelandic and Faroese also follow English in this respect,

since, like English, they developed independent of German influences.

Many French words are also intelligible to an English speaker, especially when

they are seen in writing (as pronunciations are often quite different), because English

absorbed a large vocabulary from Norman and French, via Anglo-Norman after the

Norman Conquest, and directly from French in subsequent centuries. As a result, a

large portion of English vocabulary is derived from French, with some minor spelling

differences (e.g. inflectional endings, use of old French spellings, lack of diacritics,

etc.), as well as occasional divergences in meaning of so-called false friends: for

example, compare "library" with the French librairie, which means bookstore; in

French, the word for "library" is bibliothèque. The pronunciation of most French

loanwords in English (with the exception of a handful of more recently borrowed

words such as mirage, genre, café; or phrases like coup d’état, rendez-vous, etc.) has

become largely anglicised and follows a typically English phonology and pattern of

stress (compare English "nature" vs. French nature, "button" vs. bouton, "table" vs.

table, "hour" vs. heure, "reside" vs. résider, etc.).[citation needed]

Geographical distribution

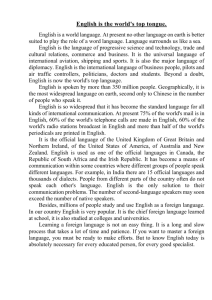

Pie chart showing the relative numbers of native English speakers in the major

English-speaking countries of the world

Approximately 375 million people speak English as their first language. English

today is probably the third largest language by number of native speakers, after

Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. However, when combining native and non-native

speakers it is probably the most commonly spoken language in the world, though

possibly second to a combination of the Chinese languages (depending on whether or

not distinctions in the latter are classified as "languages" or "dialects").

Estimates that include second language speakers vary greatly from 470 million to

over a billion depending on how literacy or mastery is defined and measured.

Linguistics professor David Crystal calculates that non-native speakers now

outnumber native speakers by a ratio of 3 to 1.

The countries with the highest populations of native English speakers are, in

descending order: United States (215 million), United Kingdom (61 million), Canada

(18.2 million), Australia (15.5 million), Nigeria (4 million), Ireland (3.8 million),

South Africa (3.7 million), and New Zealand (3.6 million) 2006 Census.

Countries such as the Philippines, Jamaica and Nigeria also have millions of

native speakers of dialect continua ranging from an English-based creole to a more

standard version of English. Of those nations where English is spoken as a second

language, India has the most such speakers ('Indian English'). Crystal claims that,

combining native and non-native speakers, India now has more people who speak or

understand English than any other country in the world.

English as a global language

Because English is so widely spoken, it has often been referred to as a "world

language", the lingua franca of the modern era, and while it is not an official language

in most countries, it is currently the language most often taught as a foreign language.

Some linguists believe that it is no longer the exclusive cultural property of "native

English speakers", but is rather a language that is absorbing aspects of cultures

worldwide as it continues to grow. It is, by international treaty, the official language

for aerial and maritime communications. English is an official language of the United

Nations and many other international organisations, including the International

Olympic Committee.

English is the language most often studied as a foreign language in the European

Union, by 89% of schoolchildren, ahead of French at 32%, while the perception of the

usefulness of foreign languages amongst Europeans is 68% in favour of English ahead

of 25% for French. Among some non-English speaking EU countries, a large

percentage of the adult population can converse in English — in particular: 85% in

Sweden, 83% in Denmark, 79% in the Netherlands, 66% in Luxembourg and over

50% in Finland, Slovenia, Austria, Belgium, and Germany.

Books, magazines, and newspapers written in English are available in many

countries around the world, and English is the most commonly used language in the

sciences with Science Citation Index reporting as early as 1997 that 95% of its articles

were written in English, even though only half of them came from authors in Englishspeaking countries.

This increasing use of the English language globally has had a large impact on

many other languages, leading to language shift and even language death, and to

claims of linguistic imperialism. English itself is now open to language shift as

multiple regional varieties feed back into the language as a whole. For this reason, the

'English language is forever evolving'.

Dialects and regional varieties

The expansion of the British Empire and—since World War II—the influence of

the United States have spread English throughout the globe. Because of that global

spread, English has developed a host of English dialects and English-based creole

languages and pidgins.

Several educated native dialects of English have wide acceptance as standards in

much of the world, with much emphasis placed on one dialect based on educated

southern British and another based on educated Midwestern American. The former is

sometimes called BBC (or the Queen's) English, and it may be noticeable by its

preference for "Received Pronunciation". The latter dialect, General American, which

is spread over most of the United States and much of Canada, is more typically the

model for the American continents and areas (such as the Philippines) that have had

either close association with the United States, or a desire to be so identified. In

Oceania, the major native dialect of Australian English is spoken as a first language

by 92% of the inhabitants of the Australian continent, with General Australian serving

as the standard accent. The English of neighbouring New Zealand as well as that of

South Africa have to a lesser degree been influential native varieties of the language.

Aside from these major dialects, there are numerous other varieties of English,

which include, in most cases, several subvarieties, such as Cockney, Scouse and

Geordie within British English; Newfoundland English within Canadian English; and

African American Vernacular English ("Ebonics") and Southern American English

within American English. English is a pluricentric language, without a central

language authority like France's Académie française; and therefore no one variety is

considered "correct" or "incorrect" except in terms of the expectations of the particular

audience to which the language is directed.

Scots has its origins in early Northern Middle English and developed and

changed during its history with influence from other sources, but following the Acts

of Union 1707 a process of language attrition began, whereby successive generations

adopted more and more features from Standard English, causing dialectalisation.

Whether it is now a separate language or a dialect of English better described as

Scottish English is in dispute, although the UK government now accepts Scots as a

regional language and has recognised it as such under the European Charter for

Regional or Minority Languages. There are a number of regional dialects of Scots,

and pronunciation, grammar and lexis of the traditional forms differ, sometimes

substantially, from other varieties of English.

English speakers have many different accents, which often signal the speaker's

native dialect or language. For the more distinctive characteristics of regional accents,

see Regional accents of English, and for the more distinctive characteristics of

regional dialects, see List of dialects of the English language. Within England,

variation is now largely confined to pronunciation rather than grammar or vocabulary.

At the time of the Survey of English Dialects, grammar and vocabulary differed across

the country, but a process of lexical attrition has led most of this variation to die out.

Just as English itself has borrowed words from many different languages over its

history, English loanwords now appear in many languages around the world,

indicative of the technological and cultural influence of its speakers. Several pidgins

and creole languages have been formed on an English base, such as Jamaican Patois,

Nigerian Pidgin, and Tok Pisin. There are many words in English coined to describe

forms of particular non-English languages that contain a very high proportion of

English words.

Constructed varieties of English

Basic English is simplified for easy international use. Manufacturers and other

international businesses tend to write manuals and communicate in Basic English.

Some English schools in Asia teach it as a practical subset of English for use by

beginners.

E-Prime excludes forms of the verb to be.

English reform is an attempt to improve collectively upon the English language.

Manually Coded English constitutes a variety of systems that have been

developed to represent the English language with hand signals, designed primarily for

use in deaf education. These should not be confused with true sign languages such as

British Sign Language and American Sign Language used in Anglophone countries,

which are independent and not based on English.

Seaspeak and the related Airspeak and Policespeak, all based on restricted

vocabularies, were designed by Edward Johnson in the 1980s to aid international

cooperation and communication in specific areas. There is also a tunnelspeak for use

in the Channel Tunnel.

Simplified Technical English was historically developed for aerospace industry

maintenance manuals and is now used in various industries.

Special English is a simplified version of English used by the Voice of America.

It uses a vocabulary of only 1500 words.

Grammar

English grammar has minimal inflection compared with most other IndoEuropean languages. For example, Modern English, unlike Modern German or Dutch

and the Romance languages, lacks grammatical gender and adjectival agreement. Case

marking has almost disappeared from the language and mainly survives in pronouns.

The patterning of strong (e.g. speak/spoke/spoken) versus weak verbs (e.g. love/loved

or kick/kicked) inherited from its Germanic origins has declined in importance in

modern English, and the remnants of inflection (such as plural marking) have become

more regular.

At the same time, the language has become more analytic, and has developed

features such as modal verbs and word order as resources for conveying meaning.

Auxiliary verbs mark constructions such as questions, negative polarity, the passive

voice and progressive aspect.

American English

American English (variously abbreviated AmE, AE, AmEng, USEng, en-US,

also known as United States English, or U.S. English) is a set of dialects of the

English language used mostly in the United States. Approximately two-thirds of

native speakers of English live in the United States.

English is the most common language in the United States. Though the U.S.

federal government has no official language, English is the common language used by

the federal government and is considered the de facto language of the United States

because of its widespread use. English has been given official status by 28 of the 50

state governments.

The use of English in the United States was as result of British colonization. The

first wave of English-speaking settlers arrived in North America in the 17th century.

During that time, there were also speakers of numerous Native American languages,

Spanish, French, Dutch, German, Norwegian, Swedish, Scots, Welsh, Irish, Scottish

Gaelic, Finnish, Russian (in Alaska), and numerous African languages (mostly from

the western coast of Africa).

Phonology

Compared to English as spoken in England, North American English is more

homogeneous. Some distinctive accents can be found on the East Coast (for example,

in eastern New England and New York City), partly because these areas were in close

contact with England and imitated prestigious varieties of British English at a time

when these were undergoing changes.[Need quotation to verify] In addition, many

speech communities on the East Coast have existed in their present locations for

centuries, while the interior of the country was settled by people from all regions of

the existing United States and developed a far more generic linguistic pattern.[citation

needed]

Most North American speech is rhotic, as English was in most places in the 17th

century. Rhoticity was further supported by Hiberno-English, West Country English

and Scottish English as well as the fact most regions of England at this time also had

rhotic accents. In most varieties of North American English, the sound corresponding

to the letter r is a retroflex [ɻ] or alveolar approximant [ɹ] rather than a trill or a tap.

The loss of syllable-final r in North America is confined mostly to the accents of

eastern New England, New York City and surrounding areas and the coastal portions

of the South, and African American Vernacular English. In rural tidewater Virginia

and eastern New England, 'r' is non-rhotic in accented (such as "bird", "work", "first",

"birthday") as well as unaccented syllables, although this is declining among the

younger generation of speakers.[citation needed] Dropping of syllable-final r

sometimes happens in natively rhotic dialects if r is located in unaccented syllables or

words and the next syllable or word begins in a consonant. In England, the lost r was

often changed into [ə] (schwa), giving rise to a new class of falling

diphthongs.[citation needed]Furthermore, the er sound of fur or butter, is realized in

AmE as a monophthongal r-colored vowel (stressed [ɝ] or unstressed [ɚ] as

represented in the IPA).[citation needed] This does not happen in the non-rhotic

varieties of North American speech.[citation needed]

The shift of /æ/ to /ɑ/ (the so-called "broad A") before /f/, /s/, /θ/, /ð/, /z/, /v/

alone or preceded by a homorganic nasal. This is the difference between the British

Received Pronunciation and American pronunciation of bath and dance.[citation

needed] In the United States, only eastern New England speakers took up this

modification, although even there it is becoming increasingly rare.[citation needed]

The realization of intervocalic /t/ as a glottal stop [ʔ] (as in [bɒʔəl] for bottle).

This change is not universal for British English and is not considered a feature of

Received Pronunciation.[citation needed] This is not a property of most North

American dialects. Newfoundland English is a notable exception.[citation needed]

On the other hand, North American English has undergone some sound changes

not found in other varieties of English speech:[citation needed]

The merger of /ɑ/ and /ɒ/, making father and bother rhyme.[citation needed]This

change is nearly universal in North American English, occurring almost everywhere

except for parts of eastern New England, hence the Boston accent.[citation needed]

The merger of /ɑ/ and /ɔ/.[citation needed] This is the so-called cot-caught

merger, where cot and caught are homophones. This change has occurred in eastern

New England, in Pittsburgh and surrounding areas, and from the Great Plains

westward.[citation needed]

For speakers who do not merge caught and cot: The replacement of the cot vowel

with the caught vowel before voiceless fricatives (as in cloth, off [which is found in

some old-fashioned varieties of RP]), as well as before /ŋ/ (as in strong, long), usually

in gone, often in on, and irregularly before /ɡ/ (log, hog, dog, fog [which is not found

in British English at all]).

The replacement of the lot vowel with the strut vowel in most utterances of the

words was, of, from, what and in many utterances of the words everybody, nobody,

somebody, anybody; the word because has either /ʌ/ or /ɔ/;[7] want has normally /ɔ/

or /ɑ/, sometimes /ʌ/.

Vowel merger before intervocalic /ɹ/. Which vowels are affected varies between

dialects, but the Mary-marry-merry, nearer-mirror, and hurry-furry mergers are all

widespread. Another such change is the laxing of /e/, /i/ and /u/ to /ɛ/, /ɪ/ and /ʊ/

before /ɹ/, causing pronunciations like [pɛɹ], [pɪɹ] and [pjʊɹ] for pair, peer and pure.

The resulting sound [ʊɹ] is often further reduced to [ɝ], especially after palatals, so

that cure, pure, mature and sure rhyme with fir.

Dropping of /j/ is more extensive than in RP. In most North American accents, /j/

is dropped after all alveolar and interdental consonant, so that new, duke, Tuesday,

resume are pronounced /nu/, /duk/, /tuzdeɪ/, /ɹɪzum/.

æ-tensing in environments that vary widely from accent to accent; for example,

for many speakers, /æ/ is approximately realized as [eə] before nasal consonants. In

some accents, particularly those from Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City,

[æ] and [eə] contrast sometimes, as in Yes, I can [kæn] vs. tin can [keən].

The flapping of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ to alveolar tap [ɾ] before unstressed

vowels (as in butter, party) and syllabic /l/ (bottle), as well as at the end of a word or

morpheme before any vowel (what else, whatever). Thus, for most speakers, pairs

such as ladder/latter, metal/medal, and coating/coding are pronounced the same. For

many speakers, this merger is incomplete and does not occur after /aɪ/; these speakers

tend to pronounce writer with [əɪ] and rider with [aɪ]. This is a form of Canadian

raising but, unlike more extreme forms of that process, does not affect /aʊ/. In some

areas and idiolects, a phonemic distinction between what elsewhere become

homophones through this process is maintained by vowel lengthening in the vowel

preceding the formerly voiced consonant, e.g., [læ:·ɾɹ̩] for "ladder" as opposed to

[læ·ɾɹ̩] for "latter".

T-glottalization is common when /t/ is in the final position of a syllable or word

(get, fretful: [ɡɛʔ], [ˈfɹɛʔfəl]), though this is always superseded by the aforementioned

rules of flapping

Both intervocalic /nt/ and /n/ may be realized as [n] or [ɾ̃], rarely making winter

and winner homophones. Most areas in which /nt/ is reduced to /n/, it is accompanied

further by nasalization of simple post-vocalic /n/, so that V/nt/ and V/n/ remain

phonemically distinct. In such cases, the preceding vowel becomes nasalized, and is

followed in cases where the former /nt/ was present, by a distinct /n/. This stopabsorption by the preceding nasal /n/ does not occur when the second syllable is

stressed, as in entail.

The pin-pen merger, by which [ɛ] is raised to [ɪ] before nasal consonants, making

pairs like pen/pin homophonous. This merger originated in Southern American

English but is now also sometimes found in parts of the Midwest and West as well,

especially in people with roots in the mountainous areas of the Southeastern United

States.

Some mergers found in most varieties of both American and British English

include:[citation needed]

The merger of the vowels /ɔ/ and /o/ before 'r', making pairs like horse/hoarse,

corps/core, for/four, morning/mourning, etc. homophones.

The wine-whine merger making pairs like wine/whine, wet/whet, Wales/whales,

wear/where, etc. homophones, in most cases eliminating /hw/, the voiceless labiovelar

fricative. Many older varieties of southern and western American English still keep

these distinct, but the merger appears to be spreading.

Vocabulary

North America has given the English lexicon many thousands of words,

meanings, and phrases. Several thousand are now used in English as spoken

internationally.

Creation of an American lexicon

The process of coining new lexical items started as soon as the colonists began

borrowing names for unfamiliar flora, fauna, and topography from the Native

American languages. Examples of such names are opossum, raccoon, squash and

moose (from Algonquian). Other Native American loanwords, such as wigwam or

moccasin, describe articles in common use among Native Americans. The languages

of the other colonizing nations also added to the American vocabulary; for instance,

cookie, cruller, stoop, and pit (of a fruit) from Dutch; levee, portage ("carrying of

boats or goods") and (probably) gopher from French; barbecue, stevedore, and rodeo

from Spanish.

Among the earliest and most notable regular "English" additions to the American

vocabulary, dating from the early days of colonization through the early 19th century,

are terms describing the features of the North American landscape; for instance, run,

branch, fork, snag, bluff, gulch, neck (of the woods), barrens, bottomland, notch,

knob, riffle, rapids, watergap, cutoff, trail, timberline and divide[citation needed].

Already existing words such as creek, slough, sleet and (in later use) watershed

received new meanings that were unknown in England.[citation needed]

Other noteworthy American toponyms are found among loanwords; for example,

prairie, butte (French); bayou (Choctaw via Louisiana French); coulee (Canadian

French, but used also in Louisiana with a different meaning); canyon, mesa, arroyo

(Spanish); vlei, kill (Dutch, Hudson Valley).

The word corn, used in England to refer to wheat (or any cereal), came to denote

the plant Zea mays, the most important crop in the U.S., originally named Indian corn

by the earliest settlers; wheat, rye, barley, oats, etc. came to be collectively referred to

as grain (or breadstuffs). Other notable farm related vocabulary additions were the

new meanings assumed by barn (not only a building for hay and grain storage, but

also for housing livestock) and team (not just the horses, but also the vehicle along

with them), as well as, in various periods, the terms range, (corn) crib, truck, elevator,

sharecropping and feedlot.[citation needed]

Ranch, later applied to a house style, derives from Mexican Spanish; most

Spanish contributions came after the War of 1812, with the opening of the West.

Among these are, other than toponyms, chaps (from chaparreras), plaza, lasso, bronco,

buckaroo, rodeo; examples of "English" additions from the cowboy era are bad man,

maverick, chuck ("food") and Boot Hill; from the California Gold Rush came such

idioms as hit pay dirt or strike it rich. The word blizzard probably originated in the

West. A couple of notable late 18th century additions are the verb belittle and the

noun bid, both first used in writing by Thomas Jefferson.[citation needed]

With the new continent developed new forms of dwelling, and hence a large

inventory of words designating real estate concepts (land office, lot, outlands,

waterfront, the verbs locate and relocate, betterment, addition, subdivision), types of

property (log cabin, adobe) in the 18th century; frame house, apartment, tenement

house, shack, shanty in the 19th century; project, condominium, townhouse, splitlevel, mobile home, multi-family in the 20th century), and parts thereof (driveway,

breezeway, backyard, dooryard; clapboard, siding, trim, baseboard; stoop (from

Dutch), family room, den; and, in recent years, HVAC, central air, walkout

basement).[citation needed]

Ever since the American Revolution, a great number of terms connected with the

U.S. political institutions have entered the language; examples are run, gubernatorial,

primary election, carpetbagger (after the Civil War), repeater, lame duck and pork

barrel. Some of these are internationally used (e.g. caucus, gerrymander, filibuster,

exit poll).[citation needed]

The rise of capitalism, the development of industry and material innovations

throughout the 19th and 20th centuries were the source of a massive stock of

distinctive new words, phrases and idioms. Typical examples are the vocabulary of

railroading (see further at rail terminology) and transportation terminology, ranging

from names of roads (from dirt roads and back roads to freeways and parkways) to

road infrastructure (parking lot, overpass, rest area), and from automotive terminology

to public transit (e.g. in the sentence "riding the subway downtown"); such American

introductions as commuter (from commutation ticket), concourse, to board (a vehicle),

to park, double-park and parallel park (a car), double decker or the noun terminal have

long been used in all dialects of English. Trades of various kinds have endowed

(American) English with household words describing jobs and occupations (bartender,

longshoreman, patrolman, hobo, bouncer, bellhop, roustabout, white collar, blue

collar, employee, boss [from Dutch], intern, busboy, mortician, senior citizen),

businesses and workplaces (department store, supermarket, thrift store, gift shop,

drugstore, motel, main street, gas station, hardware store, savings and loan, hock [also

from Dutch]), as well as general concepts and innovations (automated teller machine,

smart card, cash register, dishwasher, reservation [as at hotels], pay envelope, movie,

mileage, shortage, outage, blood bank).[citation needed]

Already existing English words —such as store, shop, dry goods, haberdashery,

lumber— underwent shifts in meaning; some —such as mason, student, clerk, the

verbs can (as in "canned goods"), ship, fix, carry, enroll (as in school), run (as in "run

a business"), release and haul— were given new significations, while others (such as

tradesman) have retained meanings that disappeared in England. From the world of

business and finance came breakeven, merger, delisting, downsize, disintermediation,

bottom line; from sports terminology came, jargon aside, Monday-morning

quarterback, cheap shot, game plan (football); in the ballpark, out of left field, off

base, hit and run, and many other idioms from baseball; gamblers coined bluff, blue

chip, ante, bottom dollar, raw deal, pass the buck, ace in the hole, freeze-out,

showdown; miners coined bedrock, bonanza, peter out, pan out and the verb prospect

from the noun; and railroadmen are to be credited with make the grade, sidetrack,

head-on, and the verb railroad. A number of Americanisms describing material

innovations remained largely confined to North America: elevator, ground, gasoline;

many automotive terms fall in this category, although many do not (hatchback, SUV,

station wagon, tailgate, motorhome, truck, pickup truck, to exhaust).[citation needed]

In addition to the above-mentioned loans from French, Spanish, Mexican

Spanish, Dutch, and Native American languages, other accretions from foreign

languages came with 19th and early 20th century immigration; notably, from Yiddish

(chutzpah, schmooze, tush and German —hamburger and culinary terms like

frankfurter/franks, liverwurst, sauerkraut, wiener, deli(catessen); scram, kindergarten,

gesundheit; musical terminology (whole note, half note, etc.); and apparently

cookbook, fresh ("impudent") and what gives? Such constructions as Are you coming

with? and I like to dance (for "I like dancing") may also be the result of German or

Yiddish influence.

Finally, a large number of English colloquialisms from various periods are

American in origin; some have lost their American flavor (from OK and cool to nerd

and 24/7), while others have not (have a nice day, sure) many are now distinctly oldfashioned (swell, groovy). Some English words now in general use, such as hijacking,

disc jockey, boost, bulldoze and jazz, originated as American slang. Among the many

English idioms of U.S. origin are get the hang of, take for a ride, bark up the wrong

tree, keep tabs, run scared, take a backseat, have an edge over, stake a claim, take a

shine to, in on the ground floor, bite off more than one can chew, off/on the wagon,

stay put, inside track, stiff upper lip, bad hair day, throw a monkey wrench, under the

weather, jump bail, come clean, come again?, it ain't over till it's over, what goes

around comes around, and will the real x please stand up?

Morphology

American English has always shown a marked tendency to use nouns as verbs.

Examples of verbed nouns are interview, advocate, vacuum, lobby, pressure, rear-end,

transition, feature, profile, belly-ache, spearhead, skyrocket, showcase, service (as a

car), corner, torch, exit (as in "exit the lobby"), factor (in mathematics), gun ("shoot"),

author (which disappeared in English around 1630 and was revived in the U.S. three

centuries later) and, out of American material, proposition, graft (bribery), bad-mouth,

vacation, major, backpack, backtrack, intern, ticket (traffic violations), hassle,

blacktop, peer-review, dope and OD, and, of course verbed as used at the start of this

sentence. The saying goes, 'In the US of A there is no such thing as a noun that can't

be "verbed"'.[citation needed]

Compounds coined in the U.S. are for instance foothill, flatlands, badlands,

landslide (in all senses), overview (the noun), backdrop, teenager, brainstorm,

bandwagon, hitchhike, smalltime, deadbeat, frontman, lowbrow and highbrow, hellbent, foolproof, nitpick, about-face (later verbed), upfront (in all senses), fixer-upper,

no-show; many of these are phrases used as adverbs or (often) hyphenated attributive

adjectives: non-profit, for-profit, free-for-all, ready-to-wear, catchall, low-down,

down-and-out, down and dirty, in-your-face, nip and tuck; many compound nouns and

adjectives are open: happy hour, fall guy, capital gain, road trip, wheat pit, head start,

plea bargain; some of these are colorful (empty nester, loan shark, ambulance chaser,

buzz saw, ghetto blaster, dust bunny), others are euphemistic (differently abled,

human resources, physically challenged, affirmative action, correctional facility).

Many compound nouns have the form verb plus preposition: add-on, stopover,

lineup, shakedown, tryout, spin-off, rundown ("summary"), shootout, holdup, hideout,

comeback, cookout, kickback, makeover, takeover, rollback ("decrease"), rip-off,

come-on, shoo-in, fix-up, tie-in, tie-up ("stoppage"), stand-in. These essentially are

nouned phrasal verbs; some prepositional and phrasal verbs are in fact of American

origin (spell out, figure out, hold up, brace up, size up, rope in, back up/off/down/out,

step down, miss out on, kick around, cash in, rain out, check in and check out (in all

senses), fill in ("inform"), kick in ("contribute"), square off, sock in, sock away, factor

in/out, come down with, give up on, lay off (from employment), run into and across

("meet"), stop by, pass up, put up (money), set up ("frame"), trade in, pick up on, pick

up after, lose out.

Noun endings such as -ee (retiree), -ery (bakery), -ster (gangster) and -cian

(beautician) are also particularly productive. Some verbs ending in -ize are of U.S.

origin; for example, fetishize, prioritize, burglarize, accessorize, itemize, editorialize,

customize, notarize, weatherize, winterize, Mirandize; and so are some backformations (locate, fine-tune, evolute, curate, donate, emote, upholster, peeve and

enthuse). Among syntactical constructions that arose in the U.S. are as of (with dates

and times), outside of, headed for, meet up with, back of, convince someone to..., not

to be about to and lack for.

Americanisms formed by alteration of existing words include notably pesky,

phony, rambunctious, pry (as in "pry open," from prize), putter (verb), buddy, sundae,

skeeter, sashay and kitty-corner. Adjectives that arose in the U.S. are for example,

lengthy, bossy, cute and cutesy, grounded (of a child), punk (in all senses), sticky (of

the weather), through (as in "through train," or meaning "finished"), and many

colloquial forms such as peppy or wacky. American blends include motel,

guesstimate, infomercial and televangelist.

English words that survived in the United States and not Britain

A number of words and meanings that originated in Middle English or Early

Modern English and that always have been in everyday use in the United States

dropped out in most varieties of British English; some of these have cognates in

Lowland Scots. Terms such as fall ("autumn"), faucet, diaper, candy, skillet,

eyeglasses, crib[citation needed] (for a baby), obligate, and raise a child[citation

needed] are often regarded as Americanisms. Fall for example came to denote the

season in 16th century England, a contraction of Middle English expressions like "fall

of the leaf" and "fall of the year". During the 17th century, English immigration to the

British colonies in North America was at its peak and the new settlers took the English

language with them. While the term fall gradually became obsolete in Britain, it

became the more common term in North America. Gotten (past participle of get) is

often considered to be an Americanism, although there are some areas of Britain, such

as Lancashire and North-eastern England, that still continue to use it and sometimes

also use putten as the past participle for put (which is not done by most speakers of

American English).

Other words and meanings, to various extents, were brought back to Britain,

especially in the second half of the 20th century; these include hire ("to employ"), quit

("to stop," which spawned quitter in the U.S.), I guess (famously criticized by H. W.

Fowler), baggage, hit (a place), and the adverbs overly and presently ("currently").

Some of these, for example monkey wrench and wastebasket, originated in 19thcentury Britain.

The mandative subjunctive (as in "the City Attorney suggested that the case not

be closed") is livelier in American English than it is in British English. It appears in

some areas as a spoken usage and is considered obligatory in contexts that are more

formal. The adjectives mad meaning "angry", smart meaning "intelligent", and sick

meaning "ill" are also more frequent in American (these meanings are also frequent in

Hiberno-English) than British English.

Regional differences

While written AmE is standardized across the country, there are several

recognizable variations in the spoken language, both in pronunciation and in

vernacular vocabulary. General American is the name given to any American accent

that is relatively free of noticeable regional influences.

After the Civil War, the settlement of the western territories by migrants from the

Eastern U.S. led to dialect mixing and leveling, so that regional dialects are most

strongly differentiated along the Eastern seaboard. The Connecticut River and Long

Island Sound is usually regarded as the southern/western extent of New England

speech, which has its roots in the speech of the Puritans from East Anglia who settled

in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Potomac River generally divides a group of

Northern coastal dialects from the beginning of the Coastal Southern dialect area; in

between these two rivers several local variations exist, chief among them the one that

prevails in and around New York City and northern New Jersey, which developed on

a Dutch substratum after the English conquered New Amsterdam. The main features

of Coastal Southern speech can be traced to the speech of the English from the West

Country who settled in Virginia after leaving England at the time of the English Civil

War.

Although no longer region-specific, African American Vernacular English, which

remains prevalent among African Americans, has a close relationship to Southern

varieties of AmE and has greatly influenced everyday speech of many Americans.

A distinctive speech pattern also appears near the border between Canada and the

United States, centered on the Great Lakes region (but only on the American side).

This is the Inland North Dialect—the "standard Midwestern" speech that was the basis

for General American in the mid-20th Century (although it has been recently modified

by the northern cities vowel shift). Those not from this area frequently confuse it with

the North Midland dialect treated below, referring to both collectively as

"Midwestern" in the mid-Atlantic region or "Northern" in the Southern US. The socalled '"Minnesotan" dialect is also prevalent in the cultural Upper Midwest, and is

characterized by influences from the German and Scandinavian settlers of the region

(yah for yes/ja in German, pronounced the same way).

In the interior, the situation is very different. West of the Appalachian Mountains

begins the broad zone of what is generally called "Midland" speech. This is divided

into two discrete subdivisions, the North Midland that begins north of the Ohio River

valley area, and the South Midland speech; sometimes the former is designated simply

"Midland" and the latter is reckoned as "Highland Southern". The North Midland

speech continues to expand westward until it becomes the closely related Western

dialect which contains Pacific Northwest English as well as the well-known California

English, although in the immediate San Francisco area some older speakers do not

possess the cot-caught merger and thus retain the distinction between words such as

cot and caught which reflects a historical Mid-Atlantic heritage.

The South Midland or Highland Southern dialect follows the Ohio River in a

generally southwesterly direction, moves across Arkansas and Oklahoma west of the

Mississippi, and peters out in West Texas. It is a version of the Midland speech that

has assimilated some coastal Southern forms (outsiders often mistakenly believe

South Midland speech and coastal South speech to be the same).

The island state of Hawaii has a distinctive Hawaiian Pidgin.

Finally, dialect development in the United States has been notably influenced by

the distinctive speech of such important cultural centers as Baltimore, Boston,

Charleston, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, New York City, Philadelphia and

Pittsburgh, which imposed their marks on the surrounding areas.

Differences between British English and American English

Main article: American and British English differences

American English and British English (BrE) differ at the levels of phonology,

phonetics, vocabulary, and, to a lesser extent, grammar and orthography. The first

large American dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language, was

written by Noah Webster in 1828; Webster intended to show that the United States,

which was a relatively new country at the time, spoke a different dialect from that of

Britain.

Differences in grammar are relatively minor, and normally do not affect mutual

intelligibility; these include: different use of some verbal auxiliaries; formal (rather

than notional) agreement with collective nouns; different preferences for the past

forms of a few verbs (e.g. AmE/BrE: learned/learnt, burned/burnt, and in sneak, dive,

get); different prepositions and adverbs in certain contexts (e.g. AmE in school, BrE at

school); and whether or not a definite article is used, in very few cases (AmE to the

hospital, BrE to hospital; contrast, however, AmE actress Elizabeth Taylor, BrE the

actress Elizabeth Taylor). Often, these differences are a matter of relative preferences

rather than absolute rules; and most are not stable, since the two varieties are

constantly influencing each other.

Differences in orthography are also trivial. Some of the forms that now serve to

distinguish American from British spelling (color for colour, center for centre, traveler

for traveller, etc.) were introduced by Noah Webster himself; others are due to

spelling tendencies in Britain from the 17th century until the present day (e.g. -ise for

-ize, although the Oxford English Dictionary still prefers the -ize ending) and cases

favored by the francophile tastes of 19th century Victorian England, which had little

effect on AmE (e.g. programme for program, manoeuvre for maneuver, skilful for

skillful, cheque for check, etc.).

AmE sometimes favors words that are morphologically more complex, whereas

BrE uses clipped forms, such as AmE transportation and BrE transport or where the

British form is a back-formation, such as AmE burglarize and BrE burgle (from

burglar). It should however be noted that these words are not mutually exclusive,

being widely understood and mostly used alongside each other within the two

systems.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_English

http://www.manythings.org/mp/

http://americanenglish.ua/

http://www.americanenglishbeatles.com/

http://www.google.com/

http://avenger.bos.ru/

Ministry of Higher and Secondary Specialised

Education of Uzbekistan

Sharipova Zarnigor

Tashkent 2011