SOUTHERN DIALECTS

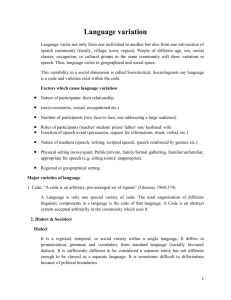

advertisement

SOUTHERN DIALECTS Southern American English is a group of dialects of the English language spoken throughout the Southern region of the United States, from Southern and Eastern Maryland, West Virginia and Kentucky to the Gulf Coast, and from the Atlantic coast to throughout most of Texas and Oklahoma. The Southern dialects make up the largest accent group in the United States.[1] Southern American English can be divided into different sub-dialects, with speech differing between regions. African American Vernacular English (AAVE) shares similarities with Southern dialect due to African Americans' strong historical ties to the region. Overview of Southern dialects The range of Southern dialects collectively known as Southern American English stretches across the southeastern and south-central United States, but excludes the southernmost areas of Florida and Texas. This linguistic region includes Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Arkansas, as well as most of Texas, Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky and West Virginia.[2][3] It also includes southern Missouri, and parts of Florida (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006). Southern dialects substantially originated from immigrants from the British Isles who moved to the South in the 17th and 18th centuries. The South was predominantly settled by immigrants from the West Country[citation needed] in the southwest of England, the dialects of which have similarities to the Southern US dialects. Settlement also included large numbers of Protestants from Ulster, Ireland, and from Scotland. During the migration south and west, the settlers encountered the French immigrants of New France (from which Kentucky, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and western Tennessee originated), and the French accent itself fused into the British and Irish accents. The modern Southern dialects were born. Phonology Few generalizations can be made about Southern pronunciation as a whole, as there is great variation between regions in the South (see the different southern American English dialects section below for more information) and between older and younger people. Upheavals such as the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and World War II caused mass migrations throughout the United States. [edit] Older SAE The following features are characteristic of older SAE: Like Australian English and English English, the English of the coastal Deep South is historically non-rhotic: it drops the sound of final /r/ before a consonant or a word boundary, so that guard sounds similar to God (but the former has a longer vowel than the latter) and stork like stalk. Intrusive /r/, where an /r/ sound is inserted at a word break between two vowel sounds ("lawr and order") is not a feature of coastal SAE, as it is in many other non-rhotic accents. Today only some areas like New Orleans, Mobile, Savannah, and Norfolk have non-rhotic speakers (Labov, Ash, and Bomberg 2006: 47-48). Non-rhoticity is rapidly disappearing from almost all Southern accents, to a greater degree than it has been lost in the other traditionally non-rhotic dialects of the East Coast such as New York and Boston. The remaining non-rhotic SAE speakers also use intrusive r, like New England and New York City. The distinction between /ɔr/ and /or/, as in horse and hoarse, for and four etc., is preserved. The wine-whine merger has not occurred, and these two words are pronounced with /w/ and /hw/ respectively. Lack of yod-dropping, thus pairs like do/due and toon/tune are distinct. Historically, words like due, lute, and new contained /juː/ (as RP does), but Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 53-54) report that the only Southern speakers today who make a distinction use a diphthong /ɪu/ in such words. They further report that speakers with the distinction are found primarily in North Carolina and northwest South Carolina, and in a corridor extending from Jackson to Tallahassee. The distinction between /ær/, /ɛr/, and /er/ in marry, merry, and Mary may be preserved by older speakers, but fewer young people make a distinction. The r-sound becomes almost a vowel, and may be elided after a long vowel, as it often is in AAVE. [edit] Newer SAE The following phenomena are relatively wide spread in Newer SAE, though degree of features may differ between different regions and between rural and urban areas. The older the speaker the less likely he or she is to have these features: The merger of [ɛ] and [ɪ] before nasal consonants, so that pen and pin are pronounced the same, but the pin-pen merger is not found in New Orleans, Savannah, or Miami (which does not fall within the Southern dialect region). This sound change has spread beyond the South in recent decades and is now found in parts of the Midwest and West as well. Lax and tense vowels often neutralize before /l/, making pairs like feel/fill and fail/fell homophones for speakers in some areas of the South. Some speakers may distinguish between the two sets of words by reversing the normal vowel sound, e.g., feel in SAE may sound like fill, and vice versa (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006: 69-73). Shared features Mean formant values for the ANAE subjects (Labov et al.) from the Southern U.S. (excluding Florida and Charleston, SC). The red symbol marks the position of monophthongized /aɪ/ before voiced consonants. The distinction between /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ is preserved mainly because /ɔ/ has an upglide. /eɪ/ is backer and lower than /ɛ/. The following features are also associated with SAE: The diphthong /aɪ/ becomes monophthongized to [aː]: o Most speakers exhibit this feature at the ends of words and before voiced consonants but not before voiceless consonants; some in fact exhibit Canadian-style raising before voiceless consonants, so that ride is [raːd] and wide is [waːd], but right is [rəɪt] and white is [hwəɪt]. Many speakers throughout the South exhibit backing to [ɑːe] in environments where monophthongization does not take place.[4] Others monophthongize /aɪ/ in all contexts, as in the stereotyped pronunciation "nahs whaht rahs" for nice white rice; these speakers are mostly found in an Appalachian area comprising eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina and Northern Alabama (the "Inland South"), and in Central Texas.[5] Elsewhere in the South this is stigmatized as a working class feature. The "Southern Drawl", breaking of the short front vowels in the words "pat", "pet", and "pit": these develop a glide up from their original starting position to IPA| [j] , and then in some cases o back down to schwa: /æ/ → [æjə]; /ɛ/ → [ɛjə]; /ɪ/ → [ɪjə]. The "Southern Shift", a chain shift following on as a result of the Southern Drawl: the nuclei of /ɛ/ and /ɪ/ move to become higher and fronter, so that, for example, instead of [ɛjə], /ɛ/ becomes a tenser /ejə. This process is most common in heavily stressed syllables. At the same time, the nuclei of the traditional front upgliding diphthongs are relaxed: /i/ moves towards [ɪi] and /eɪ/ moves towards [ɛi] or even lower and/or more retracted. The back vowels /u/ in boon and /oʊ/ in code shift considerably forward. The distinction between the vowels sounds of words like caught and cot or stalk and stock is mainly preserved. In much of the South, the vowel found in words like stalk and caught has developed into a diphthong [ɑɒ]. The nucleus of /ɑr/ card is often rounded to [ɒr]. /z/ becomes [d] before /n/, for example [wʌdn̩t] wasn't, [bɪdnɪs] business,[6] but hasn't is sometimes still pronounced [hæzənt] because there already exists a word hadn't pronounced [hædənt]. Many nouns are stressed on the first syllable that would be stressed on the second syllable in other accents. These include police, cement, Detroit, Thanksgiving, insurance, behind, display, recycle, TV, guitar, and umbrella. The distinction between /ɝ/ and /ʌr/ in furry and hurry is preserved. In some regions of the south, there is a merger of [ɔr] and [ɑr], making cord and card, for and far, form and farm etc. homonyms. The distinction between /ɪr/ and /iːr/ in mirror and nearer, Sirius and serious etc. is not preserved. /i/ is replaced with /ɛ/ at the end of a word, so that furry is pronounced /fɝrɛ/ ("furreh")[citation needed] The distinction between /ʊr/ and /ɔr/ in pour and poor, moor and more is not preserved. The l's in the words walk and talk are occasionally pronounced, causing the words talk and walk to be pronounced /wɑlk/ and /tɑlk/ by some southerners. A sample of that pronunciation can be found at http://www.utexas.edu/courses/linguistics/resources/socioling/talkmap/talk-nc.html. Some older speakers that have a phenomenon resemblant of the trap-bath split. Where General American accents perscribe /æ/ and considerably liberal accents have /ɑ:/, Southern American English may have a new vowel diphthong /æɪ/, as in aunt /æɪnt/ and gas /gæɪs/.[citation needed] [edit] Grammar [edit] Older SAE Zero copula in third person plural and second person. You [Ø] taller than Sheila. They [Ø] gonna leave today (Cukor-Avila, 2003). Use of the circumfix a- . . . -in'. He was a-hootin' and a-hollerin'. The wind was a-howlin'. The use of like to to mean nearly. I like to had a heart attack. Use of "yonder" as a determiner. They gathered a mess of raspberries in yonder woods. [edit] Newer SAE The most frequently reported second-person plural pronoun in each state, according to an Internet survey of American dialect variation.[7] Note that every state where y'all or you all was the most frequently reported form is in the South. Use of the contraction y'all as the second person plural pronoun.[8] Its uncombined form – you all – is used less frequently.[9] When speaking about a group, y'all is general (I know y'all) —as in that group of people is familiar to you and you know them as a whole, whereas all y'all is much more specific and means you know each and every person in that group, not as a whole, but individually ("I know all y'all.") Y'all can also be used with the standard "-s" possessive. "I've got y'all's assignments here." pronounced /jɔlz/ Y'all is distinctly separate from the singular you. The statement, "I gave y'all my payment last week," is more precise than "I gave you my payment last week." You (if interpreted as singular) could imply the payment was given directly to the person being spoken to – when that may not be the case. Some people misinterpret the phrase "all y'all" as meaning that Southerners use the word y'all as singular and all y'all as plural. However, all y'all is used to specify that all of the members of the second person plural are included (i.e., it functions similarly to "all of you" in standard English), that is "all y'all" as opposed to "some of y'all" In rural Southern Appalachia an "n" is added to pronouns indicating "one" "his'n" "his one" "her'n" "her one" "Yor'n" "your one" i.e. "his, hers and yours". Another example is yernses it may be substituted for the 2nd person plural possessive yours. "That book is yernses." pronounced /ˈjɜrnzez/ Use of dove as past tense for dive, drug as past tense for drag, and drunk as past tense for drink. [edit] Shared features These grammatical features are characteristic of both older Southern American English and newer Southern American English. Use of done as a redundant modal verb between the subject and verb in past simple sentences. I done told you before. Use of done (instead of did) as the past simple form of do, and similar uses of the past participle in place of the past simple, such as seen replacing saw as past simple form of see. I only done what you done told me. I seen her first. Use of other non-standard preterits, Such as drowneded as the past tense of drown, knowed as past tense of know, choosed as the past tense of choose, degradated as the past tense of degrade. I knowed you for a fool soon as I seen you. Use of was in place of were, or other words regularizing the past tense of be to was. You was sittin' on that chair. Use of been instead of have been in perfect tense formations. I been livin' here darn near my whole life. Use of double modals (might could, might should, might would, used to could, etc.--also called "modal stacking") and sometimes even triple modals that involve oughta or a double modal (like might should oughta, or used to could be able to.) I might could climb to the top. Preservation of older English me, him, etc. as reflexive datives. I'm fixin' to paint me a picture. He's gonna catch him a big one. Replacement of have (to possess) with got, or have to with got to. I got one of them. I got to get me one too. The inceptive get/got to (indicating that an action is just getting started). Get to is more frequent in older SAE, and got to in newer SAE. I got to talking to him and we ended up talking all night. Regularization of negative present tense of do to don't (instead of doesn't). This removed syllable in doesn't can also carry over to other words, turning wasn't into won't (or "weren't") or hasn't/haven't into h'aint or ain't. John don't like cake. He took a bite of my cake when I weren't looking. I h'aint seen him for ages. Merging of adjective and adverbial forms of related words (quick/quickly), generally in favor of the adjective. Similar adverbial uses include real to mean really or very, sure to mean certainly, and right to mean quite or fairly. He's movin' real quick. You sure are real pretty. I'm right tired. Saying this here in place of this or this one, and that there in place of that or that one. This here's mine and that there is yours. Using them or them there as a demonstrative adjective or noun replacing those. See them birds? Them's catbirds. Use of (a-)fixin' to as an indicator of immediate future action instead of intending to, preparing to, or about to. He's fixin' to eat. Existential It, a feature dating from Middle English which can be explained as substituting it for there when there refers to no physical location, but only to the existence of something. It's one lady that lives in town. Use of ever in place of every. Ever'where's the same these days. [edit] Vocabulary Word use tendencies from the Harvard Dialect Survey:[10] o Likely influenced by the dominance of Coca-Cola in the Deep South, a carbonated beverage in general is referred to as Coke, even if referring to non-colas. Soft drink and soda is sometimes used, usually in large cities.[11] o The shopping-cart at many stores as a buggy (or less often, jitney or trolley).[12] Use of the term "mosquito hawk", "skeeter hawk" or "snake doctor" for a dragonfly or a crane fly (Diptera tipulidae).[13] Use of "over yonder" in place of "over there" or "in or at that indicated place," especially when being used to refer to a particularly different spot, such as in "the house over yonder." Additionally, "yonder" tends to refer to a third, larger degree of distance beyond both "here" and "there," indicating that something is a long way away, and to a lesser extent, in an open expanse, as in the church hymn "When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder."[14] Use of the phrase "chill bumps" instead of "goose bumps"[15] Use of "eye" to refer to a burner on a stove. "Watch out, the eye is still hot." (Referring to the "eyes" or removable burner cover plates on, now mostly obsolete, wood or coal-fired cookstoves.)[citation needed] Use of the word "bookbag" as opposed to "backpack." [edit] Dialects It has been said that one of the features which most distinguish the South from the rest of the country is speech.[who?] However, contrary to popular belief, there is no single "Southern accent". Instead, there are a number of sub-regional dialects found across the Southern United States which are collectively known as Southern American English. Still, these different varieties often share commonalities of accent and idiom easily distinguishable from that spoken in other regions of the United States and identify it as being "Southern", particularly to other Americans. Although different "Southern" dialects exist, they are all mutually intelligible, as are US and British English more broadly. [edit] Atlantic Virginia Piedmont The Virginia Piedmont dialect is possibly the most famous of Southern dialects because of its strong influence on the South's speech patterns. Because the dialect has long been associated with the upper or aristocratic plantation class in the Old South, many of the most important figures in Southern history spoke with a Virginia Piedmont accent. Virginia Piedmont is nonrhotic, meaning speakers pronounce "R" only if it is followed by a vowel. The dialect also features the Southern drawl (mentioned above). Coastal Southern Coastal Southern resembles Virginia Piedmont but has preserved more elements from the colonial era dialect than almost any other region of the United States. It can be found along the coasts of the Chesapeake and the Atlantic in Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. It is most prevalent in the Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia areas. In addition, like Virginia Piedmont, Coastal Southern is non-rhotic. [edit] Midland and Highland South Midland or Highland Southern This dialect arose in the inland areas of the South. The area was settled largely by Scots-Irish, Scottish Highlanders, Northern and Western English, Welsh, and Germans. This dialect follows the Ohio River in a generally southwesterly direction, moves from Kentucky, across far southern Missouri and Oklahoma, and tapers out in western Texas. This dialect is used by some people in Southern Illinois and Southern Indiana. It has assimilated some coastal Southern forms, most noticeably the loss of the diphthong /aj/, which becomes /aː/, and the second person plural pronoun "you-all" or "y'all". Unlike Coastal Southern, however, South Midland is a rhotic dialect, pronouncing /r/ wherever it has historically occurred. Southern Appalachian Due to the former isolation of some regions of the Appalachian South, the Appalachian accent may be difficult for some outsiders to understand. This dialect is also rhotic, meaning speakers pronounce "R"s wherever they appear in words, and sometimes when they do not (for example "worsh" for "wash.") Because of the extensive length of the mountain chain, noticeable variation also exists within this subdialect. The Southern Appalachian dialect can be heard, as its name implies, in North Georgia, North Alabama, East Tennessee, Middle Tennessee, Western North Carolina, Eastern Kentucky, Southwestern Virginia, Western Maryland, and West Virginia. Southern Appalachian speech patterns, however, are not entirely confined to these mountain regions previously listed. The common thread in the areas of the South where a rhotic version of the dialect is heard is almost invariably a traceable line of descent from Scots or Scots-Irish ancestors amongst its speakers. The dialect is also not devoid of early influence from Welsh settlers, the dialect retaining the Welsh English tendency to pronounce words beginning with the letter "h" as though the "h" were silent; for instance "humble" often is rendered "umble". A popular myth claims that this dialect closely resembles Early Modern or Shakespearean English. [1] Although this dialect retains many words from the Elizabethan era that are no longer in common usage, this myth is apocryphal. [2] Florida Cracker This dialect is found throughout several regions of Florida and in south Georgia. There are several different variations of the dialect found in Florida. From Pensacola to Tallahassee the dialect is non-rhotic and shares many characteristics with the speech patterns of southern Alabama. Another form of the dialect is spoken in northeast Florida, Central Florida, the Nature Coast and even in rural parts of South Florida. This dialect was made famous by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings' book The Yearling. The dialect also has some distinct words to it. Some speakers may call a river turtle a "cooter", a land tortoise a "gopher", a bass a "trout", and a crappie fish a "speck" or "bream" pronounced (brɪm).[citation needed] [edit] Gulf of Mexico Gulf Southern & Mississippi Delta This area of the South was settled by English speakers moving west from Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas, along with French settlers from Louisiana (see the section below). This accent is common in Mississippi, northern Louisiana, Arkansas, western Tennessee, and East Texas. Familiar speakers include Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley. Dialects found in Georgia and Alabama that are not Southern Appalachian have characteristics of both the Gulf Southern dialect and the Virginia Piedmont/Coastal Southern dialect. Cajun Main article: Cajun French Southern Louisiana, southeast Texas (Houston to Beaumont), and coastal Mississippi, feature a number of dialects. There is Cajun French, which combines elements of Acadian French with other French and Spanish words. This dialect is spoken by many of the older members of the Cajun ethnic group and is said to be dying out. Many younger Cajuns speak Cajun English, which retains Acadian French influences and words, such as "cher" (dear) or "nonc" (uncle). The French language can also still be heard in some parts of southern Louisiana. Creole Main article: Louisiana Creole French Louisiana Creole French (Kreyol Lwiziyen) is a French-based creole language spoken in Louisiana. It has many resemblances to other French creoles in the Caribbean. While Cajun French and Louisiana Creole have had a significant influence on each other, they are unrelated. While Cajun is basically a French dialect with grammar similar to standard French, Louisiana Creole applies a French lexicon to a system of grammar and syntax which is quite different from French grammar. Yat Main article: Yat (New Orleans) This is spoken in and around the greater New Orleans area. It is referred to as Yat, from the phrases such as "Where y'at?" for "How are you?" Additionally, many unique terms such as "neutral ground"[16] for the median of a divided street (Louisiana/Southern Mississippi) or "banquette"[17] for a sidewalk (Southern Louisiana/Eastern Texas) are found here. [edit] African-influenced The following dialects were influenced by African languages. Gullah Main article: Gullah language Sometimes called Geechee, this creole language originated with African American slaves on the coastal areas and coastal islands of Georgia and South Carolina. The dialect was used to communicate with both Europeans and members of African tribes other than their own. Gullah was strongly influenced by West African languages such as Vai, Mende, Twi, Ewe, Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, and Kikongo. The name and chorus of the Christian hymn "Kumbaya" is said to be Gullah for come by here. Other English words attributed to Gullah are juke (jukebox), goober (Southern term for peanut) and voodoo. In a 1930s study by Lorenzo Dow Turner, over 4,000 words from many different African languages were discovered in Gullah. Other words, such as yez for ears, are just phonetic spellings of English words as pronounced by the Gullahs, on the basis of influence from Southern & Western English dialects. African American Vernacular English Main article: African American Vernacular English This type of Southern American English originated in the Southern States where Africans at that time were held as slaves. These slaves originally spoke indigenous African languages but were forced to speak English to communicate with their masters and each other. Since the slave masters spoke Southern American English, the English the slaves learned, which has developed into what is now African American Vernacular English, had many SAE features. While the African slaves and their descendants lost most of their language and culture, various vocabulary and grammatical features from indigenous West African languages remain in AAVE. While AAVE may also be spoken by members of other ethnic groups, it is largely spoken by and associated with blacks in many parts of the U.S. AAVE is considered by a number of English speakers to be a substandard dialect. As a result, AAVE speakers desiring social mobility typically learn to code-switch between AAVE and a more standardized English dialect. Liberian English is said to be at least partially based on AAVE, since that this type of English dialect was modeled after American English and not British English. [edit] Notes 1. ^ "Do You Speak American: What Lies Ahead". pbs.org. http://www.pbs.org/speak/ahead/. Retrieved 2007-08-15. 2. ^ Map from the Telsur Project. Retrieved 2009-08-03. 3. ^ Map from Craig M. Carver (1987), American Regional Dialects: A Word Geography, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Retrieved 2009-08-03 4. ^ A Handbook of Varieties of English: Volume 1, p. 301, 311-312 5. ^ Labov et al., p. 245. 6. ^ Wolfram, Walt; and Schilling-Estes, Natalie. (2004). American English (Second Edition). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, p. 55. 7. ^ http://www4.uwm.edu/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/states.html Harvard Dialect Survey word use: a group of two or more people. 8. ^ http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_50.html Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: a group of two or more people. 9. ^ Hazen, Kirk and Fluharty, Ellen. "Linguistic Diversity in the South: changing Codes, Practices and Ideology". Page 59. Georgia University Press; 1st Edition: 2004. ISBN .0-8203-2586-4 10. ^ Noted in the Harvard Dialect Survey 11. ^ http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_105.html Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: sweetened carbonated beverage 12. ^ http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_75.html Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: wheeled contraption at grocery store 13. ^ Definition from The Free Dictionary 14. ^ Regional Note from THe Free Dictionary 15. ^ http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_81.html Harvard Dialect Study - word use: skin bumps when cold 16. ^ "neutral ground". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000. http://www.bartleby.com/61/35/N0073575.html. Retrieved 2008-09-08. 17. ^ "banquette". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000. http://www.bartleby.com/61/44/B0064400.html. Retrieved 2008-09-15. [edit] References Bernstein, Cynthia (2003). "Grammatical features of southern speech". in In Stephen J. Nagel and Sara L. Sanders, eds.,. English in the Southern United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82264-5. Crystal, David (2000). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82348-X. Cukor-Avila, Patricia (2003). "The complex grammatical history of African-American and white vernaculars in the South". in In Stephen J. Nagel and Sara L. Sanders, eds.,. English in the Southern United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82264-5. Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8. Hazen, Kirk, and Fluharty, Ellen (2004). "Defining Appalacian English". in Bender, Margaret. Linguistic Diversity in the South. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2586-4.